The first surprise was a $200 nonrefundable fee the landlord charged to reserve the brick house that Mary McElya and her family hoped to rent. There was also $550 the landlord charged on a sliding scale based on their credit scores. The lower the score, the higher the fee.

Then McElya learned of a $39 monthly fee for a bundle of services that included emergency maintenance and renters insurance. Plus, $20 more each month for Mallory, the family cat. These and other fees pushed their rent payments from the advertised $2,195 to above $2,300, records show.

Only after a sewage pipe break sent raw sewage streaming from the toilets and shower drains of the Stone Mountain house, coating the floors and splashing onto the walls, did McElya realize that the extra fees for renter insurance covered the landlord, not them. And despite the emergency maintenance fee, repairs dragged on for weeks, according to emails with their management company. The family was forced to pay more than $5,200 for hotels and Airbnbs, their receipts show.

“We’re covered for nothing,” McElya said. “No one has even cared.”

Landlords across metro Atlanta and nationally are tacking extra fees on top of rent, squeezing household budgets as rents remain sky-high and as many large landlords continue to make strong profits, earnings reports show. These additional payments, called junk fees by critics, pop up in leases for suburban single-family houses, high-end apartments and crumbling, chronically violent complexes. They can increase monthly payments to $100 or more over advertised rent, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution examination of leases and other records shows.

Other states ban many of these fees. But they may be legal in Georgia, which continues to have some of the nation’s weakest renter protections after a bill to strengthen them failed to cross the finish line during this year’s legislative session. Landlords argue that state law allows them to add on charges if they disclose them to tenants and used them pay for services and extra perks.

Yet all these additional fees are no guarantee of better service, or that landlords provide what they charged for at all, the AJC found. Tenants complain of broken air conditioning, mold, and extra fees for pest control that they never receive.

Credit: Ben Gray

Credit: Ben Gray

Housing experts worry that the fees are solely designed to wring more profits from families during an affordable housing crisis. They said tenants often cannot walk away from an available rental, even if they think they are being charged unfairly. There’s too little housing available, at any price.

“It is just taking more money from folks who are already struggling,” said Steve Sharpe, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center, which issued a report on rental fees in March. “It is a wide enough phenomenon in the rental market that it is absolutely a place that’s deserving of federal intervention.”

Fine print

Local housing lawyers said it became clear during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic that these fees had become common, when residents facing eviction after layoffs or unpaid sick leave called Atlanta Legal Aid Society for help. The amounts they owed were far higher than their unpaid rent alone, said Katie Herring, an attorney in its Cobb County office.

On top of rent, tenants paid monthly fees for cable and internet they had trouble accessing, credit monitoring they did not request or other services that were rarely provided such as “valet trash,” where garbage is hauled from a renter’s doorstep to a dumpster. Some tenants appeared to be over-charged or charged twice for the same service, Herring said.

Landlords charged extra if tenants have low or no credit, or if residents choose to pay by check instead of electronically, leases and research by advocacy groups show. Other charges were for services that are customarily included in rent, such as sorting mail or delivering notices to tenants. McElya’s third-party property manager, California-based startup PURE Property Management, charges a fee if a tenant’s phones or emails stop working, her lease says.

While these charges can be legal in Georgia if landlords clearly disclose them, attorneys found they were buried in the fine print of leases that were 30 pages or longer. Renters said they were not given a chance to read them until after paying application and administration fees that can top $100.

“We think a lot of this conduct is intended to deceive tenants into entering into these lease agreements,” said Herring, whose nonprofit filed a test case against Tampa-based multifamily operator American Landmark arguing that Georgia’s Fair Business Practices Act bars landlords from charging such fees.

Fees pushed plaintiff Danielle Jackson’s monthly payments at Marietta-area The Franklin at East Cobb from $1,295 to as high as $1,450, the lawsuit states. Jackson, who works as a patient care coordinator, said she struggled to find anyone at the leasing office who could explain the fees. All communication was done virtually because of the pandemic.

“[Rental fees are] just taking more money from folks who are already struggling."

A $25 valet trash service rarely arrived, leaving garbage rotting in the hallways, the suit alleges. Jackson’s $4 a month pest control never came. Repairs were slow, forcing her to spend two weeks without electricity and two months without hot water. A toilet failed to work for three weeks. Costs for utilities that were billed through the landlord climbed, even when maintenance problems forced her to use them less.

“I was to the point where I just felt like I was tricked,” Jackson said. Medical bills for her teenage daughter’s rare health condition piled up, while unpaid leave for Jackson’s bouts with COVID-19 drained her savings. Her landlord filed for eviction when she could no longer pay rent on time.

An attorney for American Landmark said all fees are clearly disclosed and in compliance with Georgia law, and that tenants confirm they have read and understood their leases during signing.

Source of profit

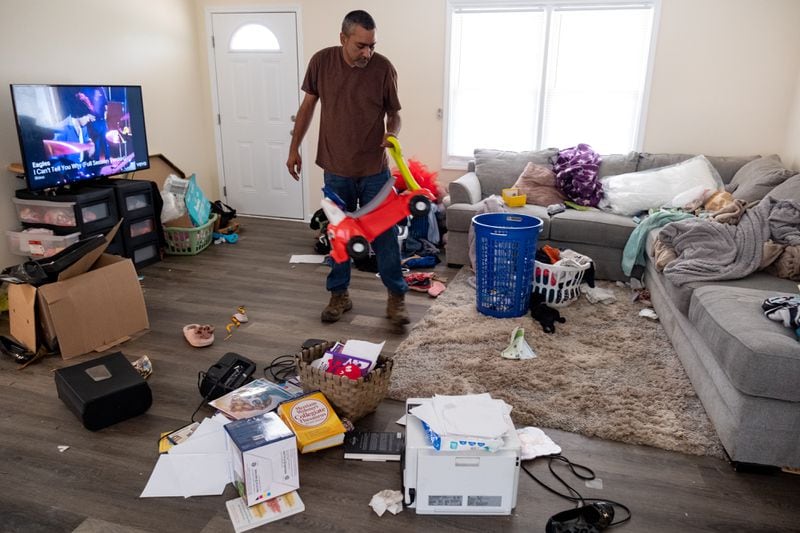

Newly arrived from South Carolina, McElya said she and her husband, Rajesh Desor, signed a lease for the Stone Mountain-area home because they thought extra fees were customary in metro Atlanta. The renovated ranch with stainless steel appliances and granite countertops would be a beautiful home for Lenore, their toddler daughter. Two blond horses lived on the lot next door.

“My daughter can wake up every day to this,” she thought. “We’re good.”

The sewage backup took place in April, about two weeks after the family moved in.

Credit: Ben Gray

Credit: Ben Gray

PURE Property Management Vice President David LaPlante declined to talk about the specifics of the case, but he said that for the 2-year-old company to grow, it must serve the owners of its 25,000 properties who demand these fees.

“Unfortunately that’s just math and the economics behind it,” LaPlante said.

For some large landlords, these fees mean more money. Invitation Homes was on track to make about $30 million on fees alone last year, while Tricon Residential hoped to raise fees by 30% per home, according to a 2022 University of California, Berkeley report on corporate landlords of single-family rentals.

Mid-America Apartment Communities executives said that they finished its 2022 fiscal year ahead of expectations, in part because of higher income from fees, advocacy group Accountable.US noted in a recent report.

“Corporations have gotten hip to the idea that they can pad their profits by dropping in these hidden fees that consumers don’t really find out about until they get the bill, or they sign the contract,” said Liz Zelnick, who oversees the group’s economic projects.

Housing attorneys in Georgia and elsewhere have seen landlords collect non-refundable fees from applicants they know are not eligible to rent because of prior evictions, criminal records or low credit scores, a March National Consumer Law Center report states. Complaints to the Georgia attorney general’s office raise concerns that some large landlords collect application fees when they have no home to rent out.

Feds respond

Even fees that landlords clearly disclose may be pernicious, worsening racial and ethnic inequities in wealth and other areas.

Black and Latino renters in Atlanta and across the country submit more applications during their home searches than white renters, while renters of color pay on average as much as double each time they submit one, Zillow researchers found in 2022. Their security deposits were higher, too, stripping them of significant wealth, report author Manny Garcia said. A typical renter holds only $3,400 across savings, checking, retirement and investment accounts.

Evictions, lower credit scores and criminal histories disproportionately impact people of color, warned Eric Dunn, a lawyer at the National Housing Law Project. Less likely to be accepted to rent the most desirable housing, and unwilling to lose hundreds of dollars applying to multiple rentals, non-white residents may decide to apply in neighborhoods where there are fewer jobs, struggling schools and scant opportunities for their families to get ahead.

“It’s almost certain that these fees produce a significant amount of residential steering by race,” Dunn said.

Such concerns led U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Marcia Fudge to call for state and local governments and landlords to limit fees to those legitimately needed to perform a service and to disclose bottom-line costs accurately in advertising and leases. The Biden administration’s tenant Bill of Rights, a non-binding call for more tenant protections, also backs clearly written leases without hidden fees.

Some states, including Massachusetts, Vermont and Washington, bar or limit certain fees, but with Georgia’s laws unclear, tenants continue to fend for themselves. McElya and her family are still fighting to get reimbursed for the thousands they spent on emergency housing after the Stone Mountain home’s sewage pipe broke. They recently signed a lease on a different house.

“This new place is not fee-ing us to death,” McElya said.

Jackson moved to her father’s house in Marietta with her teen daughter, who was declared legally blind. Jackson still breaks down when she talks about her ordeal at The Franklin.

“It’s sad that I’m not the only person who’s going through this,” Jackson said. “It just hurts.”

About the Author

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/5G3UVWBZSC5CT4LDTUCKYNCHNE.JPG)