It’s a given that most original American music — country and western, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, the blues — came from the South.

What is astonishing is how much of it came from Georgia. In 1923 Fiddlin’ John Carson recorded perhaps the first country music hit in an Atlanta hotel. Albany native Ray Charles gave birth to soul music — but not before leaving Georgia far behind.

And who invented rock ‘n’ roll? In the words of “Kinky Boots” star Billy Porter, “Sorry, y’all. It wasn’t Elvis.”

In the AJC’s documentary film on Southern hip-hop, “The South Got Something to Say,” Atlanta taste-maker Jason Orr (founder of the FunkJazz Kafe) gives props to Georgia’s Mount Rushmore, the four giants of R&B music who ought to have their faces on their own mountain. They are James Brown, Ray Charles, Otis Redding and Little Richard.

How did one Deep South state generate so much funk? (And to be more specific, how did one sleepy Middle Georgia town incubate three out of the four of these colossal figures?)

Not only that, how did all four emerge from crushing poverty to take over the music world? “We’re not talking about well-educated men who got college degrees,” said Deanna Brown, the daughter of the Godfather of Soul. “They were young, poor Black men who came from the segregated South, and they changed music completely. And we’re still talking about them so many years after, and they’re all gone. And that common ground that you mentioned, that common ground was called soul.”

The Quasar of Rock

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

In Macon they will tell you that it all started with Little Richard.

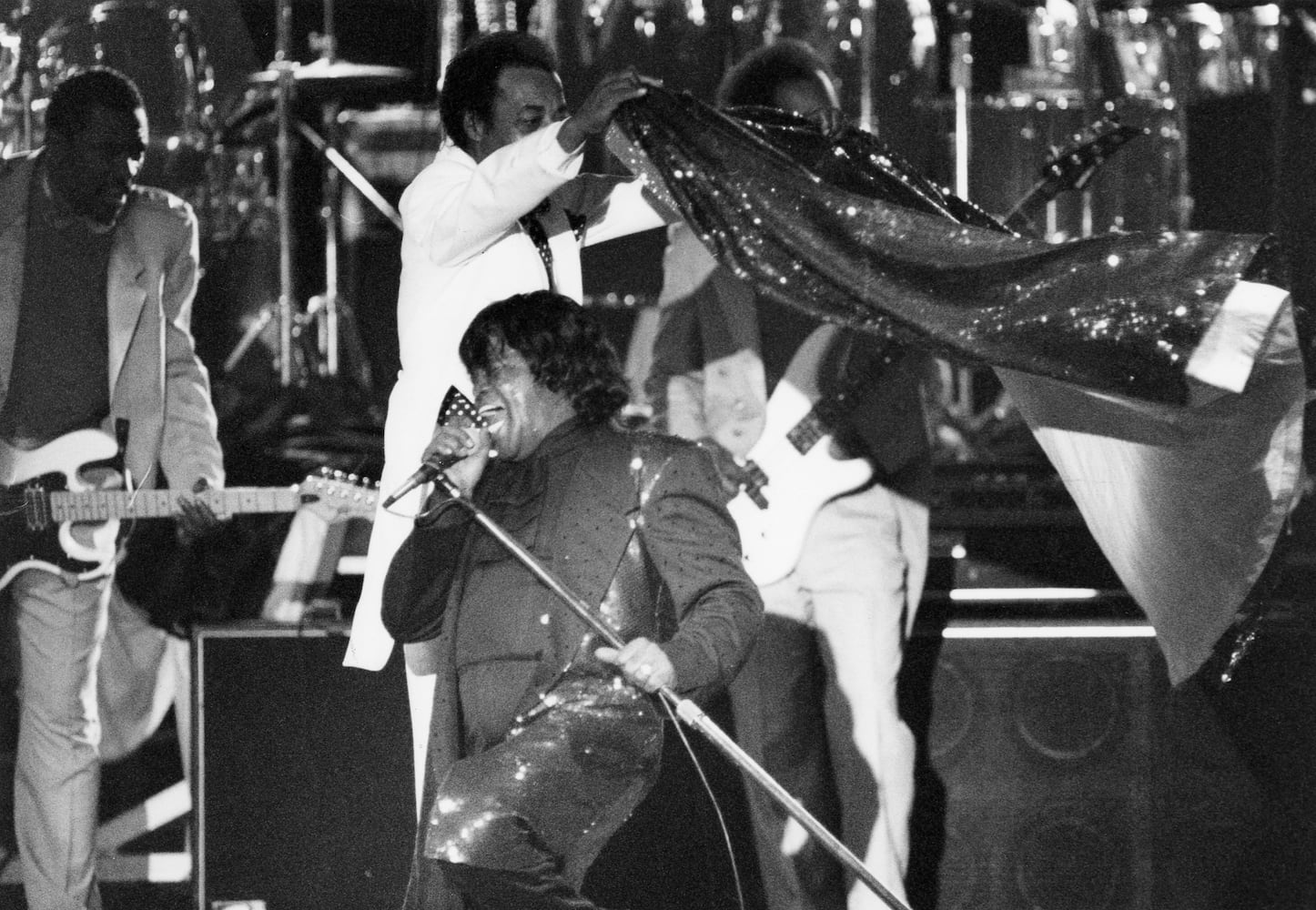

His wild, conked-up hair, his swishing capes and onstage antics made him a local celebrity long before the rest of the world caught on. National fame took him to Los Angeles, and his inheritors, James Brown and Otis Redding, tried to catch some of that Little Richard spark.

In Macon, Redding won the talent contest at Hamp Swain’s Teenage Dance Party 15 times in a row, usually singing Little Richard songs such as “Heeby-Jeebies.” In Richard’s absence he sang with Richard’s backing band, the Upsetters, to help support his family.

In 1955, the Flames with member James Brown jumped onto the stage during the intermission at a Little Richard show in Toccoa and grabbed a moment in the spotlight, drawing the eye of Richard’s manager Clint Brantley. After Richard abruptly left Georgia, Brantley fulfilled some already-scheduled gigs by putting Brown in front of the Upsetters, and introducing him as “Little Richard.”

Redding and Brown got their start trying to be Little Richard.

The Genius of Soul

Credit: AP FILE

Credit: AP FILE

Born in 1930, he was already making grownup music when his Georgia colleagues were playing for teen dances.

He wrote in his autobiography “Brother Ray,” “(M)y stuff was more adult, filled with more despair than anything you’d associate with rock ‘n’ roll.”

He had reason to despair. Of the four Georgians, Charles’ childhood was the bleakest.

His mother Aretha Robinson, was impregnated, then abandoned, by her adoptive father in Greenville, Florida. In 1930 young R.C. Robinson was born in Albany, Georgia, but when he was an infant his mother returned to Greenville, where she worked as a laundress.

R.C. began to lose his eyesight at age 4 or 5, but not before he saw his brother George drown in his mother’s washtub. At 7 R.C. was sent to live, on his own, at the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind in St. Augustine. He was 14 when his mother died, leaving him utterly alone in a dark world.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

He was alone, but also supremely talented. At the Florida school he had learned piano, trumpet and saxophone. He mastered reading Braille music and was trained in Chopin, Mozart, Art Tatum and Artie Shaw. He moved to Jacksonville, joined the musician’s union, and at age 17 took his $600 life savings and relocated as far away from the segregated South as possible, to Seattle.

Seven years later Charles was rolling through Atlanta on tour (so the story goes) and heard the gospel hymn “I’ve Got a Savior” on the radio. He turned that song into the secular rave-up “I’ve Got a Woman,” harnessed gospel passion to R&B and made magic.

Of the quartet of music giants, Ray Charles had the slimmest connection to the state, living here as an infant only a matter of months. But as fate would have it, in 1960 he borrowed a 30-year-old tune from Indiana songwriter Hoagy Carmichael and made it into a No. 1 hit; “Georgia on My Mind” would forever enshrine Ray Charles’ soulful voice as the universal representative of the Peach State.

Educated and polished, Ray Charles was the diametric opposite of the uninhibited Little Richard, who was kicked out of Macon for driving around with a naked woman in his car while she had sex with another man.

Charles and Richard had one thing in common, however, a valuable connection with a record industry man named Robert “Bumps” Blackwell. In 1948 in Seattle, Charles met Blackwell, who introduced him to a teenaged prodigy, Quincy Jones. Charles played in Blackwell’s band and played piano on Guitar Slim’s million-seller, “The Things That I Used to Do,” a session put together by Blackwell for Art Rupe’s Specialty Records.

In 1952 Charles signed with Atlantic Records and began to score hits with songs such as “Mess Around” and ”It Should Have Been Me.” In the meantime Blackwell was scouting talent for Specialty, trying to find someone to compete with Charles.

“Tutti Frutti”

In 1955 Little Richard mailed an audition tape to Rupe, and, after some delay, Rupe sent for him. The story has often been told about the disappointing recording session at Cosimo Matassa’s studio in the back of a New Orleans furniture store, in which Richard’s uninspired ballads did not live up to his wild appearance.

“If you look like Tarzan but sound like Mickey Mouse it just doesn’t work out,” Blackwell told Richard’s biographer Charles White. Blackwell called for a break, took the musicians to lunch at a tavern across the street where Richard sat down at the piano and ripped into a dirty little tune he once might have belted out at Miss Ann’s Tick Tock in Macon.

That was it! Blackwell hustled the group back to the studio and replaced the risqué verses with some cleaner lyrics. In three takes Richard recorded “Tutti Frutti” and invented rock ‘n’ roll.

The single sold 200,000 copies in a week and a half. It spent 22 weeks on the R&B chart and would go on to sell 3 million. Richard was ready to get out of Macon and moved with his whole family, including his mother, to Los Angeles, into a house next door to boxing great Joe Louis.

Hit after hit followed, including “Long Tall Sally,” “Slipping and Sliding” and “Good Golly Miss Molly.” But within two years Richard would experience a vision during a tour of Australia and decide to give up rock ‘n’ roll and become a preacher.

“Dock of the Bay”

Richard’s colleagues capitalized on his absence. “Otis saw it as a chance to fill that vacuum,” Alan Walden told the AJC in 2015.

While still a teenager, Alan was working with his brother Phil Walden’s artist management company. Their star client was Otis Redding.

Credit: Courtesy Zelma Redding

Credit: Courtesy Zelma Redding

In between gigs at white fraternities and Black clubs, Redding also worked digging wells and pumping gas, trying to help the family while his father was in the hospital with tuberculosis.

But his mind was always on music. “He got fired from a number of jobs for singing,” said his daughter Karla Redding-Andrews, vice president and executive director of the Otis Redding Foundation. “My dad could not keep a job.”

Walden got Redding’s music in front of Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records, who, in turn, arranged for sessions at the storied Memphis label Stax (which had a distribution deal with Atlantic). “These Arms of Mine” and “Pain in My Heart” resulted. Otis was off and running.

Whenever Redding arrived at Stax for a recording session, it was an event. “It was exciting” recalled William Bell, who was Redding’s predecessor at Stax and recorded the first charted tune that put Stax on the map, “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” from 1961.

Bell said one never knew what to expect at a Redding recording session. “He never really wrote a whole song down. It was always just the first line of the first paragraph, first line of the second paragraph, but it was all in his head — the horn lines, the bass lines, he kept all of it in his head.”

Bell, an Atlanta resident since 1974, toured with Redding and provided background vocals on some of his songs, including “Respect.” Aretha Franklin’s cover of “Respect” eclipsed Redding’s, becoming an international phenomenon and the battle hymn for the women’s movement. When Redding performed his version at the Monterrey Pop Festival in 1967, he jokingly introduced it as the song “that a girl took away from me.”

Credit: Otis Redding Foundation

Credit: Otis Redding Foundation

On Dec. 10, 1967, on the way to a concert engagement in Madison, Wisconsin, Redding’s private plane, a twin-engine Beechcraft, went down in bad weather. The plane crashed into the 34-degree waters of Lake Monona, killing Redding, his pilot, an assistant, and four members of his band the Bar-Kays. Redding was 26 years old.

The next month his song “(Sittin’ on the) Dock of the Bay” was released posthumously, reaching No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

The singer had begun planning a summer camp for disadvantaged kids before his death, and the Otis Redding Foundation, overseen by Redding-Andrews, is carrying on that work. In addition to sponsoring a music camp and after-school program, the foundation is building a $7 million Otis Redding Center for the Arts in Macon, expected to open in October.

“We are not looking to create the next Otis Redding, or Little Richard or James Brown,” said Redding-Andrews. “We are looking to have a place where kids can express themselves, be musically and artistically creative, a place where they can bond together, and if music or art happens to be the end result, so be it.”

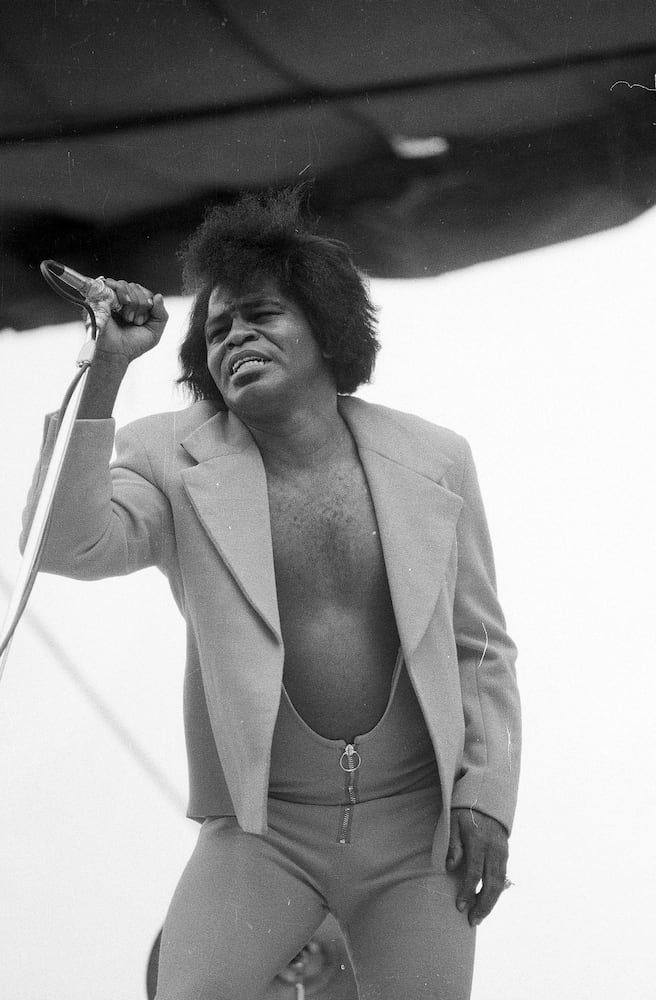

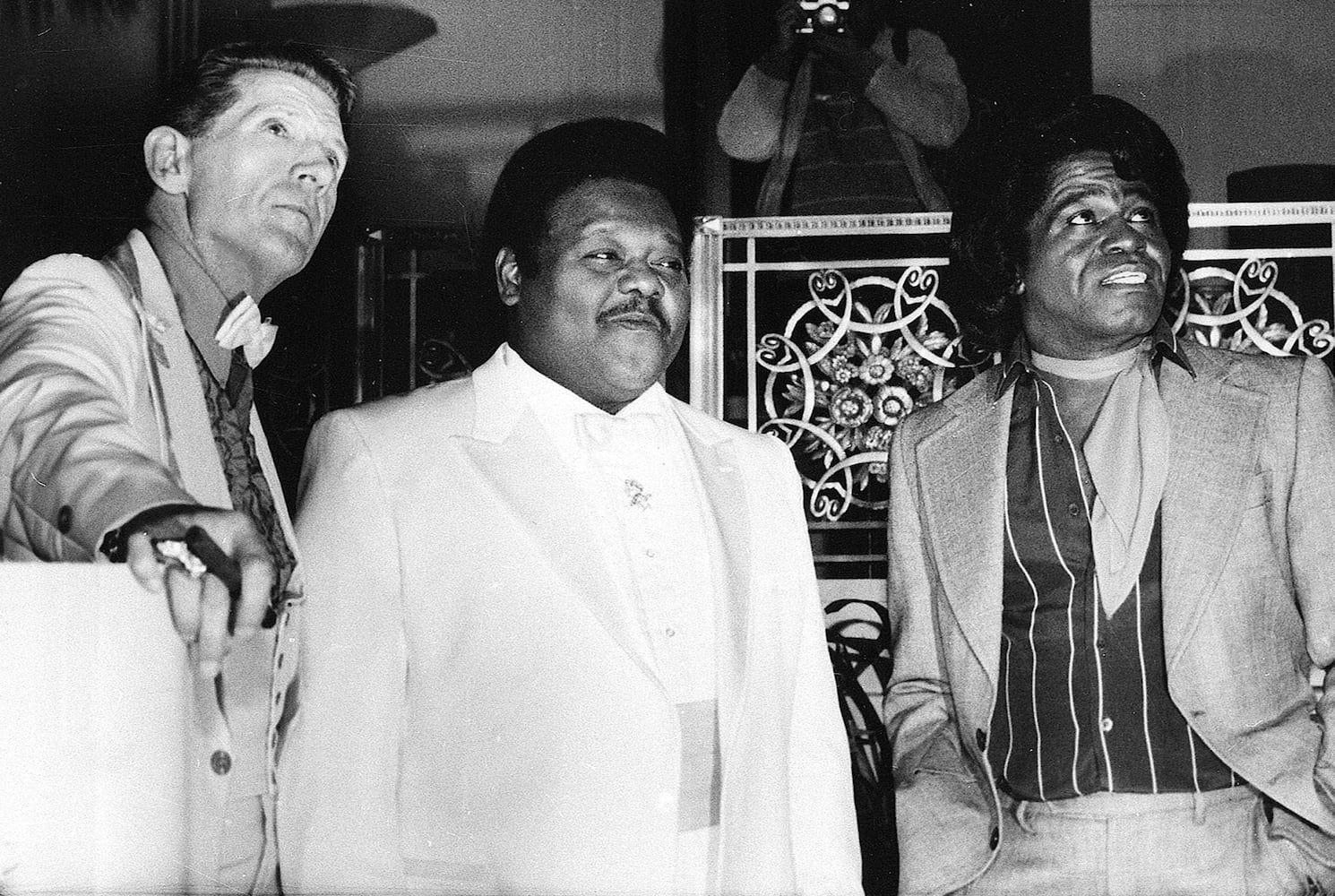

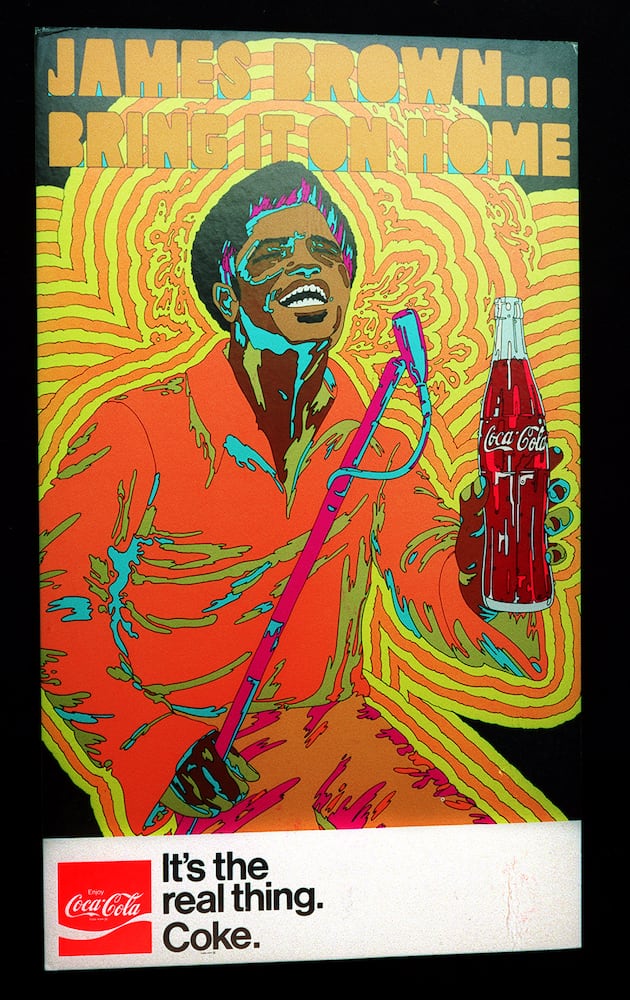

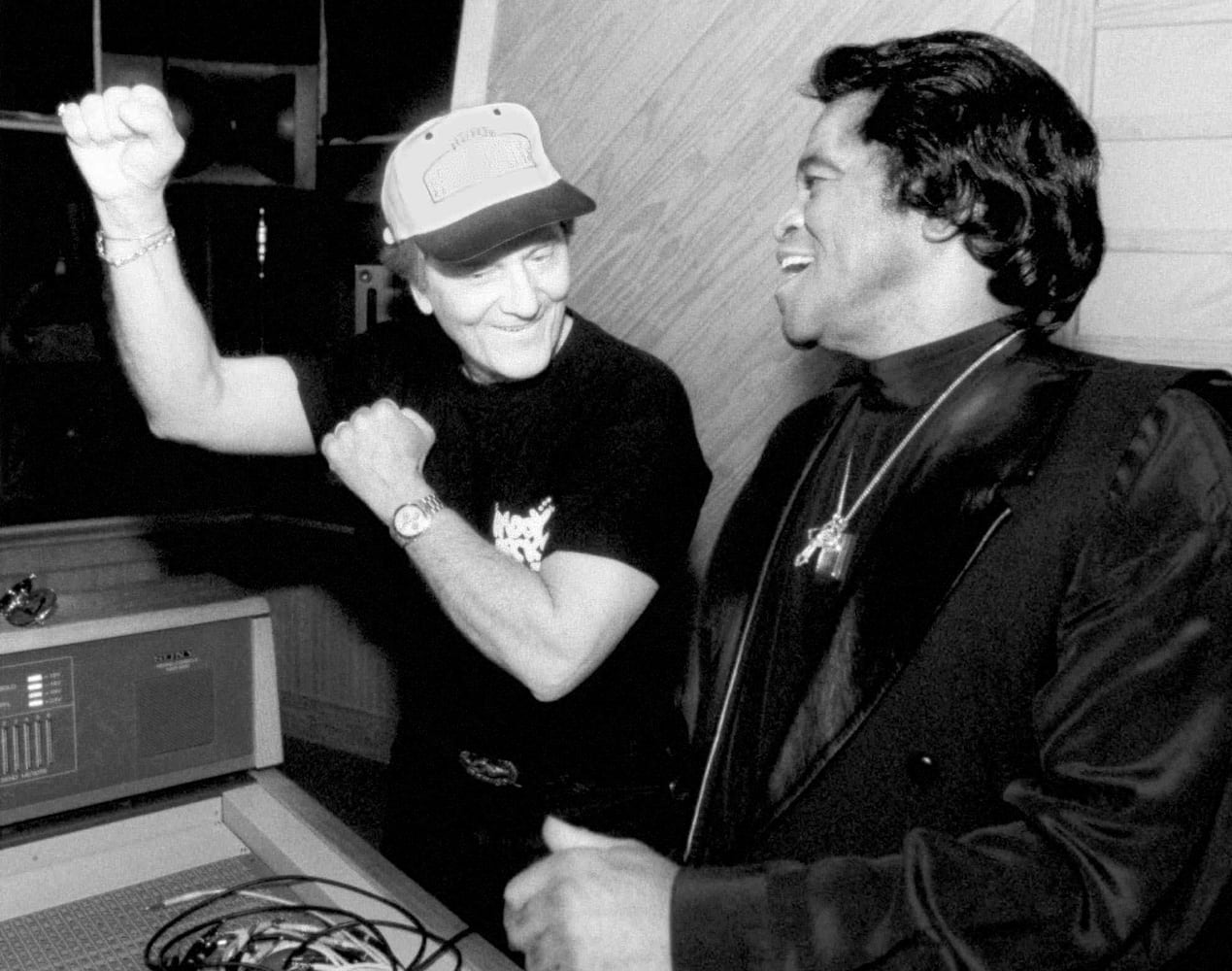

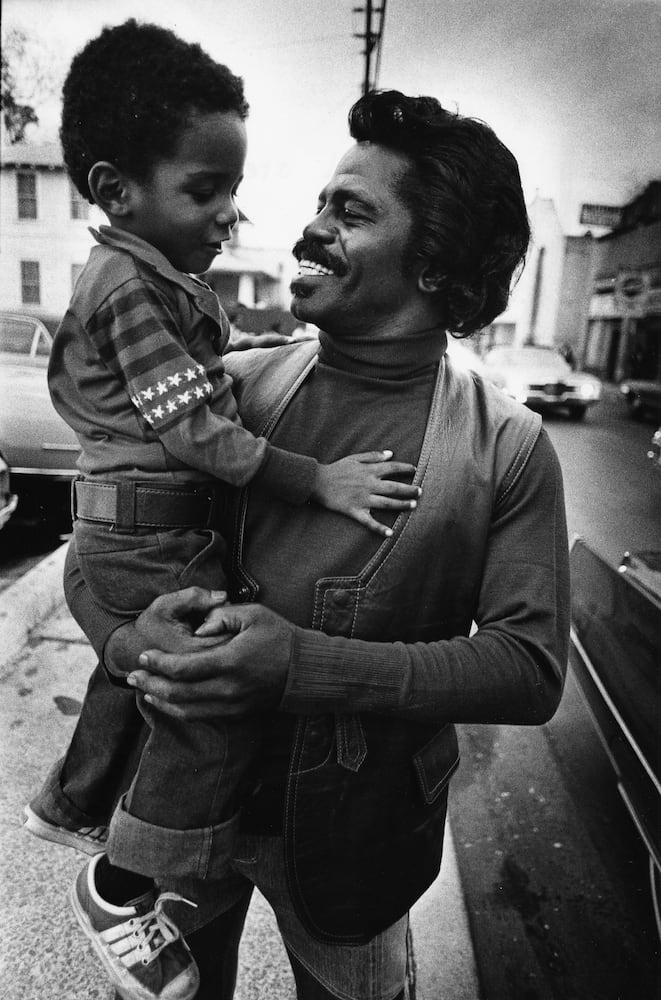

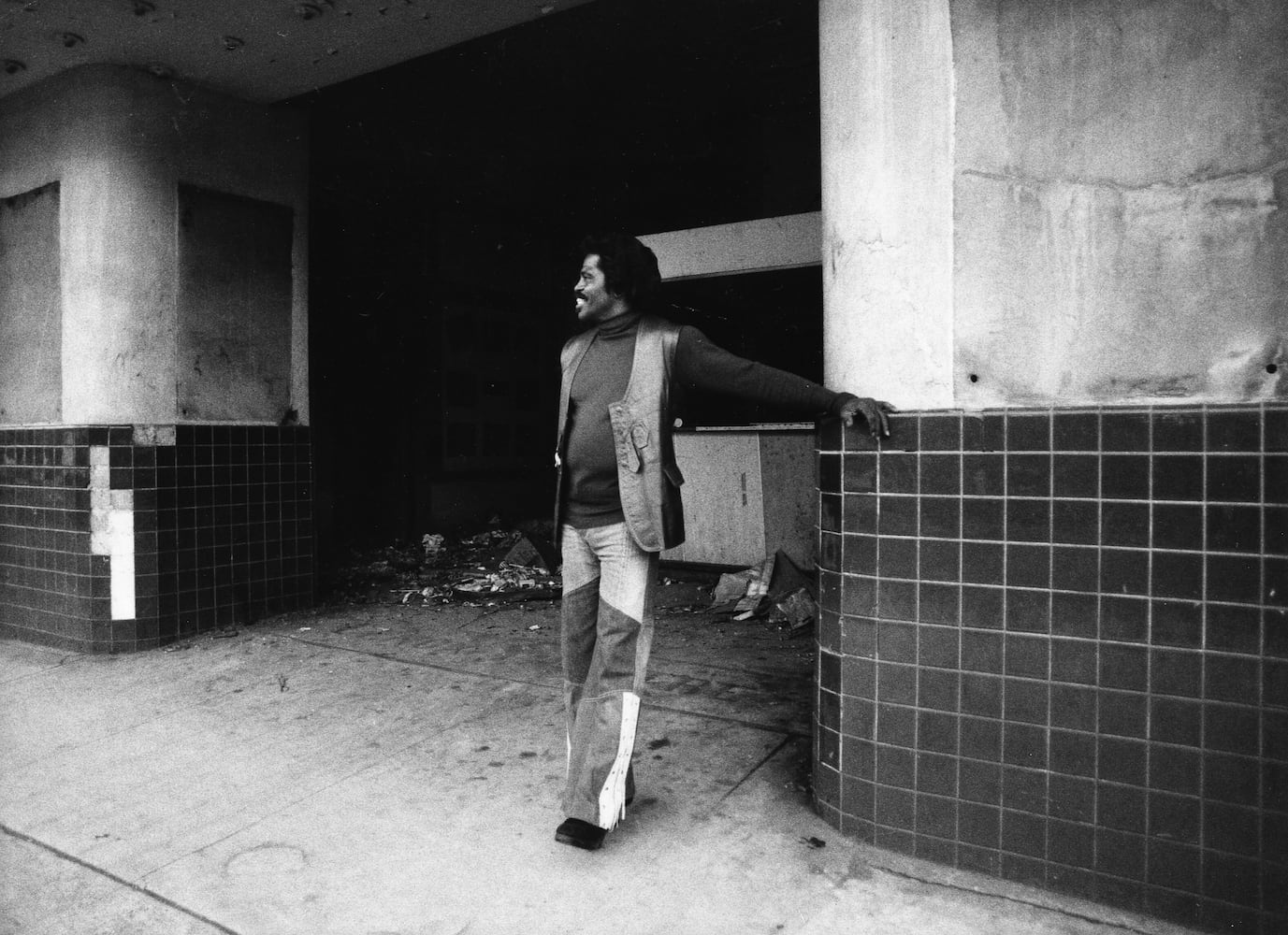

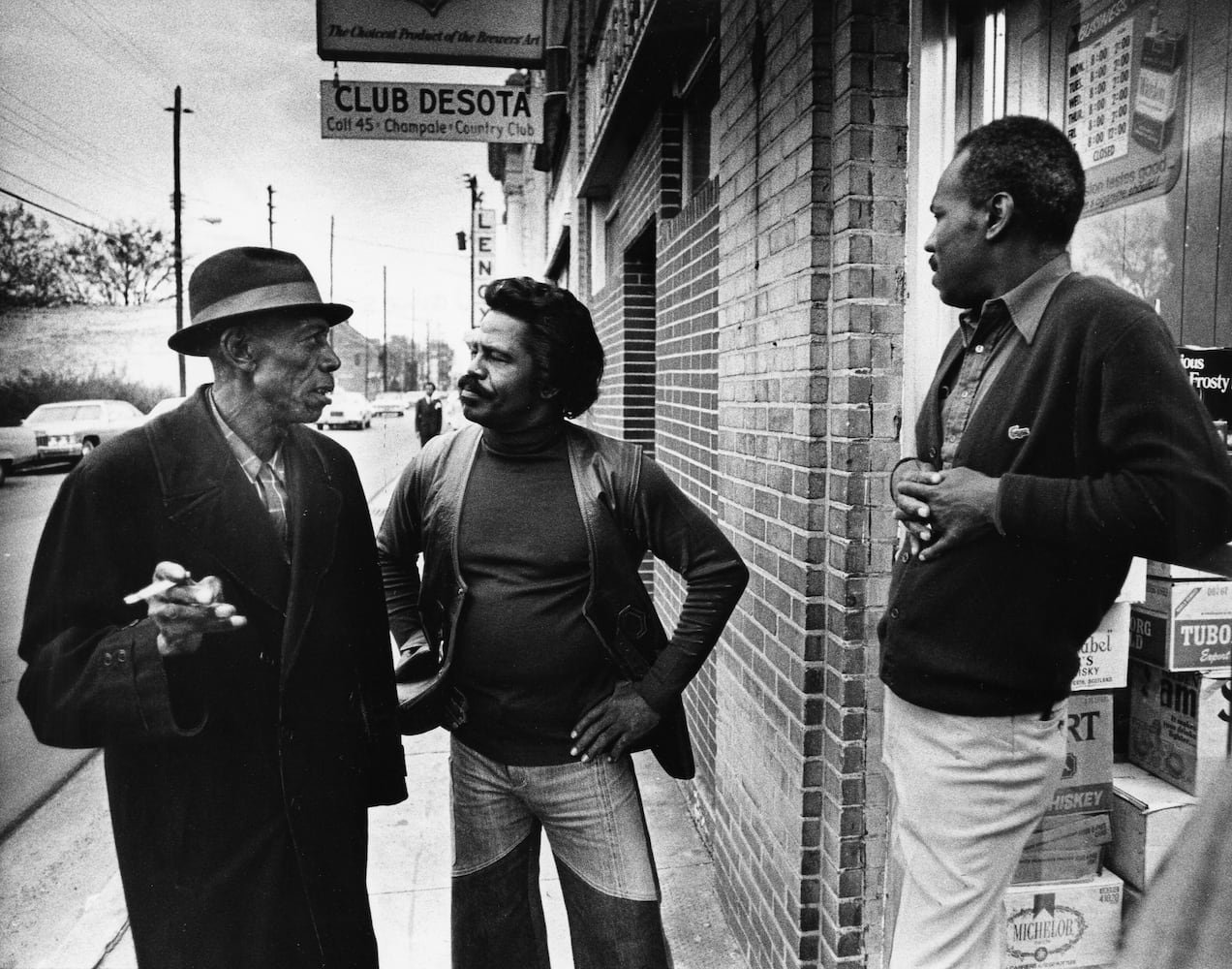

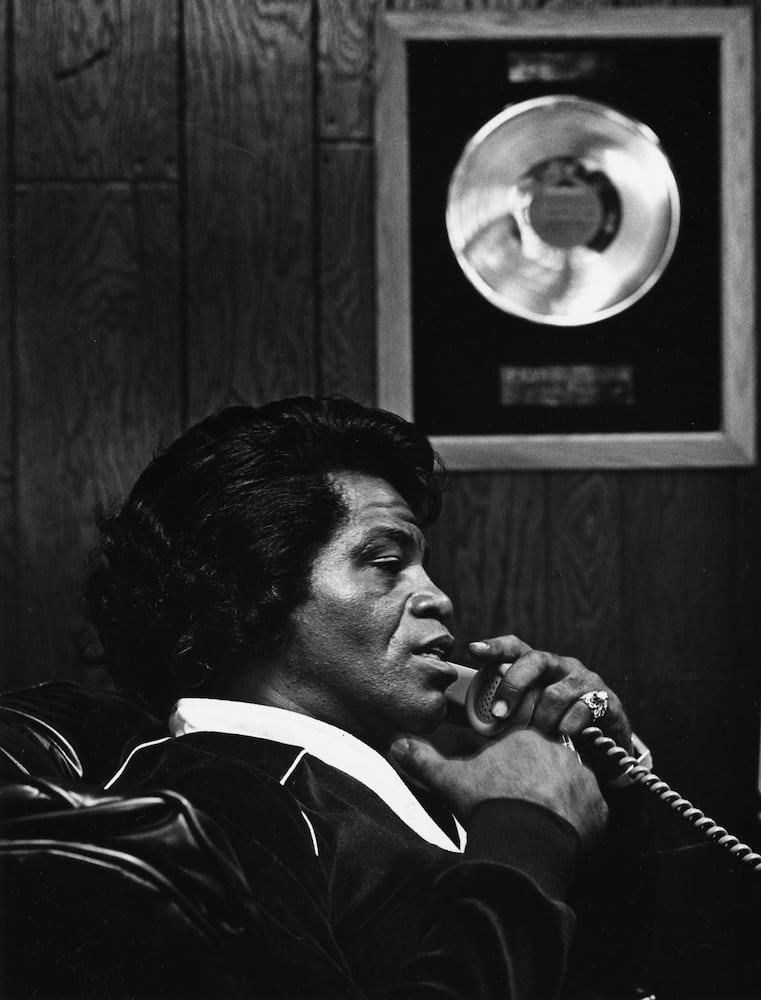

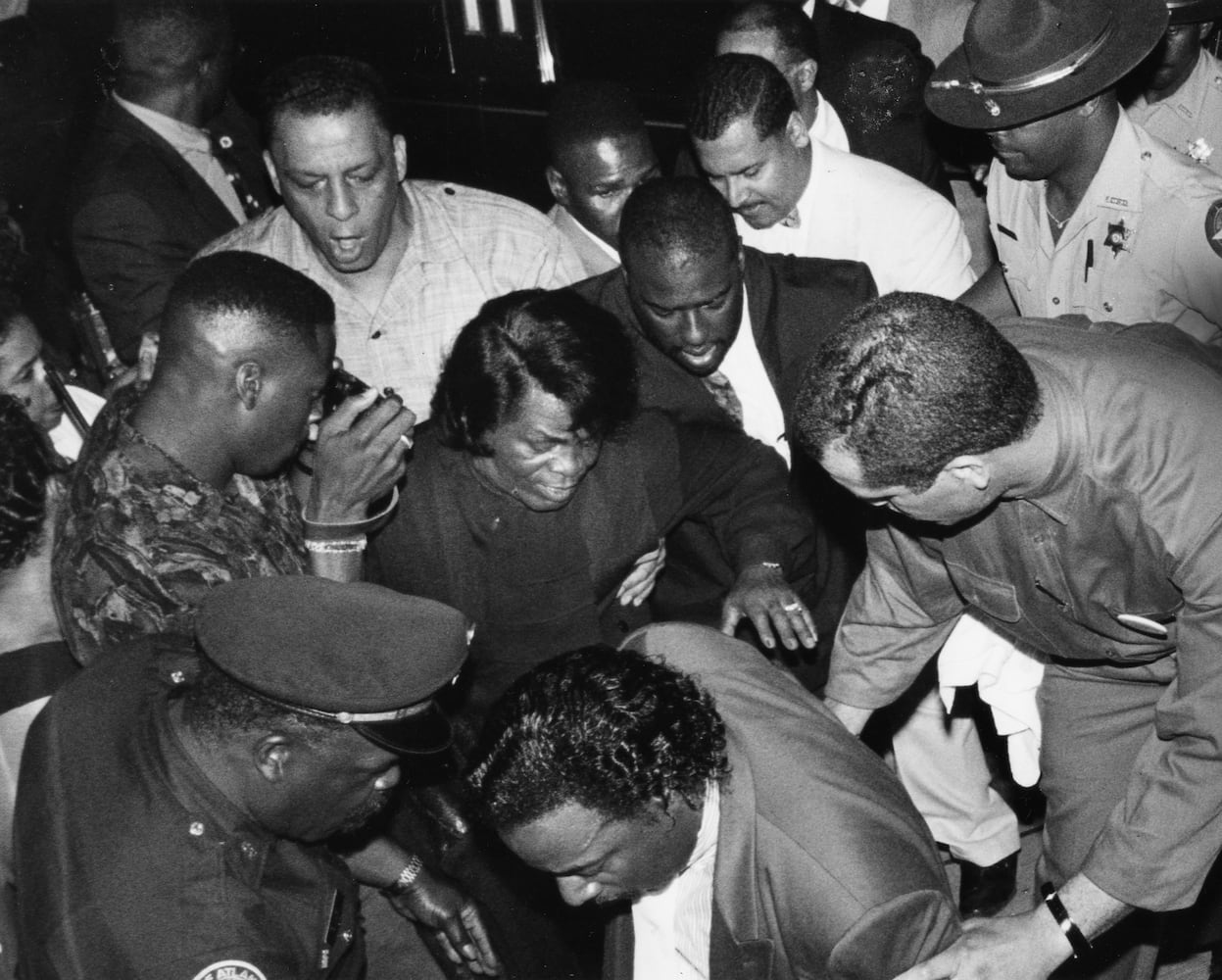

The Godfather

Credit: Photo courtesy of the University of Georgia

Credit: Photo courtesy of the University of Georgia

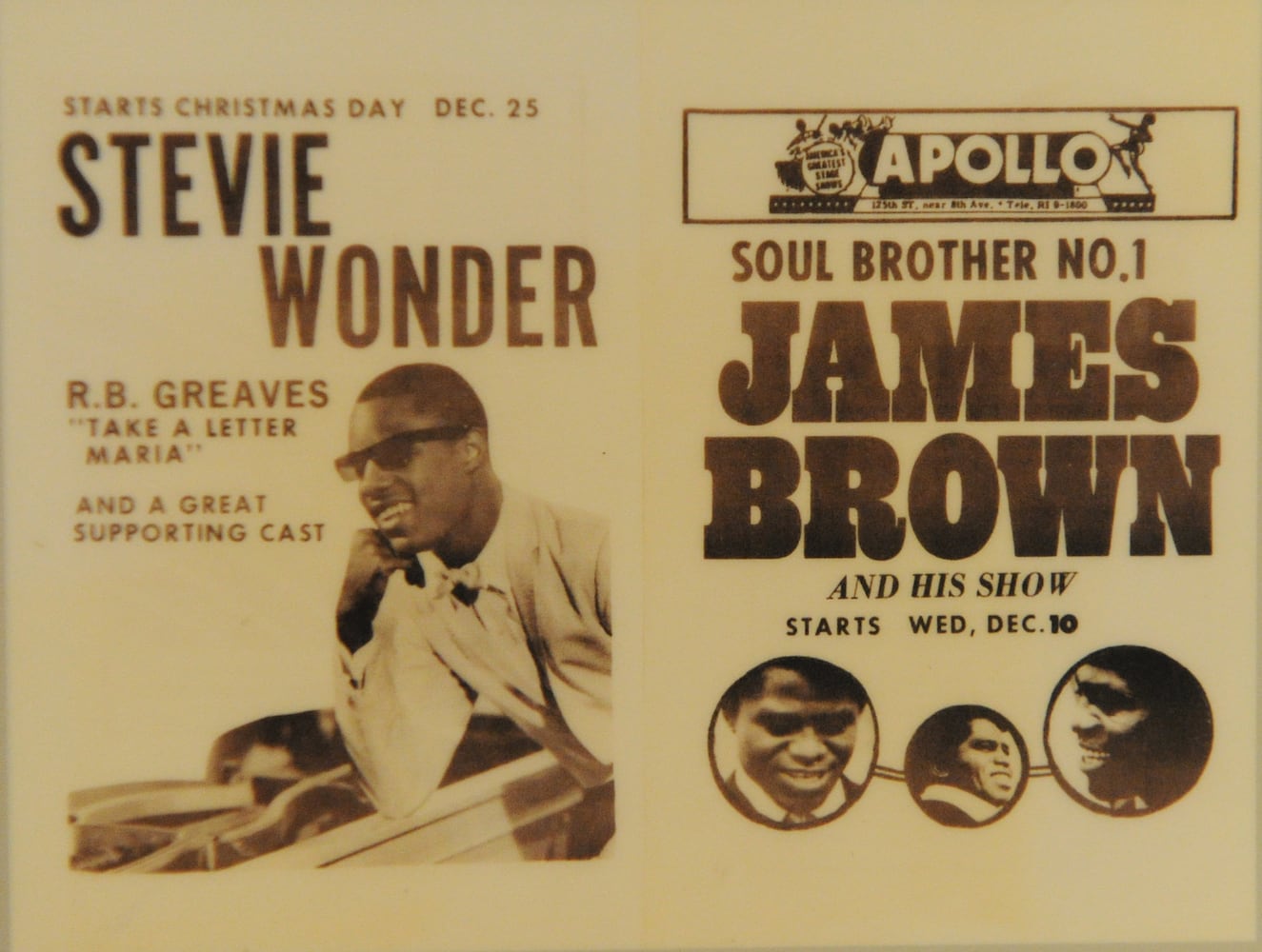

After Clint Brantley brought James Brown and the Famous Flames to Macon in 1955, he arranged for them to visit radio station WIBB and cut a demo of “Please, Please, Please,” featuring Brown’s sobbing, begging vocals.

That recording earned them a deal with Syd Nathan’s King Records in Cincinnati; the Flames all signed, though Brown quickly emerged as the leader. Their singles did not sell well, but Brown’s dynamic, sweat-soaked stage show, perfected through relentless touring, attracted a growing following.

R&B historian Nelson George writes that Brown played “five to six one-nighters a week from the mid-sixties through the early seventies.” The occasional day off would become a work day when Brown became inspired and went into the studio to record tunes such as “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” and “I Got You (I Feel Good).”

“He could call up the engineer [at King Records] any time of the day or night, and say, ‘Meet me at the studio,’” said Deanna Brown.

With the help of band members such as saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis and bassist Bootsy Collins, he wove together the sharp, spiky horn stabs, multiple drummers and abrupt, stuttering bass lines that became funk.

Serving as his own promoter, writer, arranger, choreographer and iron-fisted band-leader, Brown turned himself and his band into an industry. “As a businessman with a long and lucrative career based on astute self-management, he was a sterling example, and advocate, of black self-sufficiency,” George wrote.

Though a conservative believer in capitalism, Brown also promoted Black power. His 1968 song, “Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud,” worried some white audiences. “Radio stations pulled that song because it was ‘too militant’,” said his daughter.

Nathan wouldn’t pay for a live recording of Brown’s performance at the Apollo, so Brown paid for it himself, recording the midnight show on Oct. 24, 1962.

“Live at the Apollo” became one of the greatest live albums of all time, capturing the intensity of an evening with Brown and his entourage of two-dozen musicians, singers and crew.

Of the four giants, James Brown maintained the strongest connection to Georgia until his death in 2006, giving out turkeys and toys in Augusta each Christmas.

But it was Ray Charles whose voice became the voice of Georgia. His 1960 recording of “Georgia on My Mind,” floating on a cushion of strings and close-harmony backup vocalists, became his first No. 1 single. In 1979 the Georgia legislature designated his version as the official state song. And in 2007 a bronze statue of Charles was erected in Albany, his birthplace, and, for a very brief period of time, his home.

So whether it’s soulful, doleful, blazing, bawdy or funky, y’all can thank Georgia for that old sweet song.

About the Author