Otis Redding: Georgia native left legacy for the world

During the month of February, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution will publish a daily feature highlighting African American contributions to our state and nation. This is the fifth year of the AJC Sepia Black History Month series. In addition to the daily feature, the AJC also will publish deeper examinations of contemporary African American life each Sunday.

He was known as the “King of Soul.”

Rolling Stone magazine called Otis Redding one of the best vocalists. Ever.

His songs were legendary. Hits such as “Try A Little Tenderness,” “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay,” “Respect,” “These Arms of Mine” and “Mr. Pitiful” were filled with raw emotion, whether he was singing about loneliness or advising men to be tender to their lovers.

To Karla Redding-Andrews, though, he was just dad.

"Dad worked hard. Mom worked hard," said Redding-Andrews, vice president and executive director of the Otis Redding Foundation in Macon, the city where the singer spent most of his life. "He went to work, and he came home."

It wasn’t until she and her brothers were older that they understood that his “work” made him an international star and etched his name in music history forever.

She remembers going with her mother, Zelma, and brother, Otis III, to watch a performance at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. James Brown and her dad were on the bill.

When Redding stepped on the stage, the audience went crazy.

»RELATED: Atlanta’s Gladys Knight

His fans included other singers, like Janis Joplin and Rod Stewart, who marveled at his powerful style and were influenced by his work. Aretha Franklin covered his “Respect.”

“The simplest way I would put it is that Otis was one of the greatest singers of the greatest generation of African American singers that we’ve ever had in this country, and that’s saying a lot,” said Jonathan Gould, author of “Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life.”

Aretha Franklin. Sam Cooke. Otis Redding.

They all came up in the church at a time when church music and preaching were being revolutionized by the amplification of radio, said Gould.

They took the expressive elements of gospel and secularized the sound.

“Otis was within that constellation of great singers,” said Gould. “Each of them had a different specialty. Sam Cooke was extraordinarily gifted as a vocalist. Ray Charles had this very raw carnality. Wilson Pickett had more of the same. Solomon Burke had this great humor. Otis, Otis I always felt had this devotional quality. The way he performed a song conveyed this enormous sense of romantic devotion.”

Born in Dawson, Ga., Redding was the son of Baptist preacher and a housewife. He was one of six children.

» MORE: Full coverage of Black History Month

As a teen, Redding would often compete in local talent shows, "winning consistently until he was no longer allowed to compete," according to Macon Music Trail, an online resource for the city's musical history.

While other African Americans were leaving the South to find better lives in the North, Redding stayed in Georgia and started his music career.

His first single, “These Arms of Mine,” was released on the Stax Records label in 1962.

“Dad never left because he loved the Macon community and had established a home base for his family outside of Macon in Round Oak,” said Redding-Andrews. He had set up various businesses in Macon and had plans to open a recording studio and restaurants.

»RELATED: Augusta’s Jessye Norman

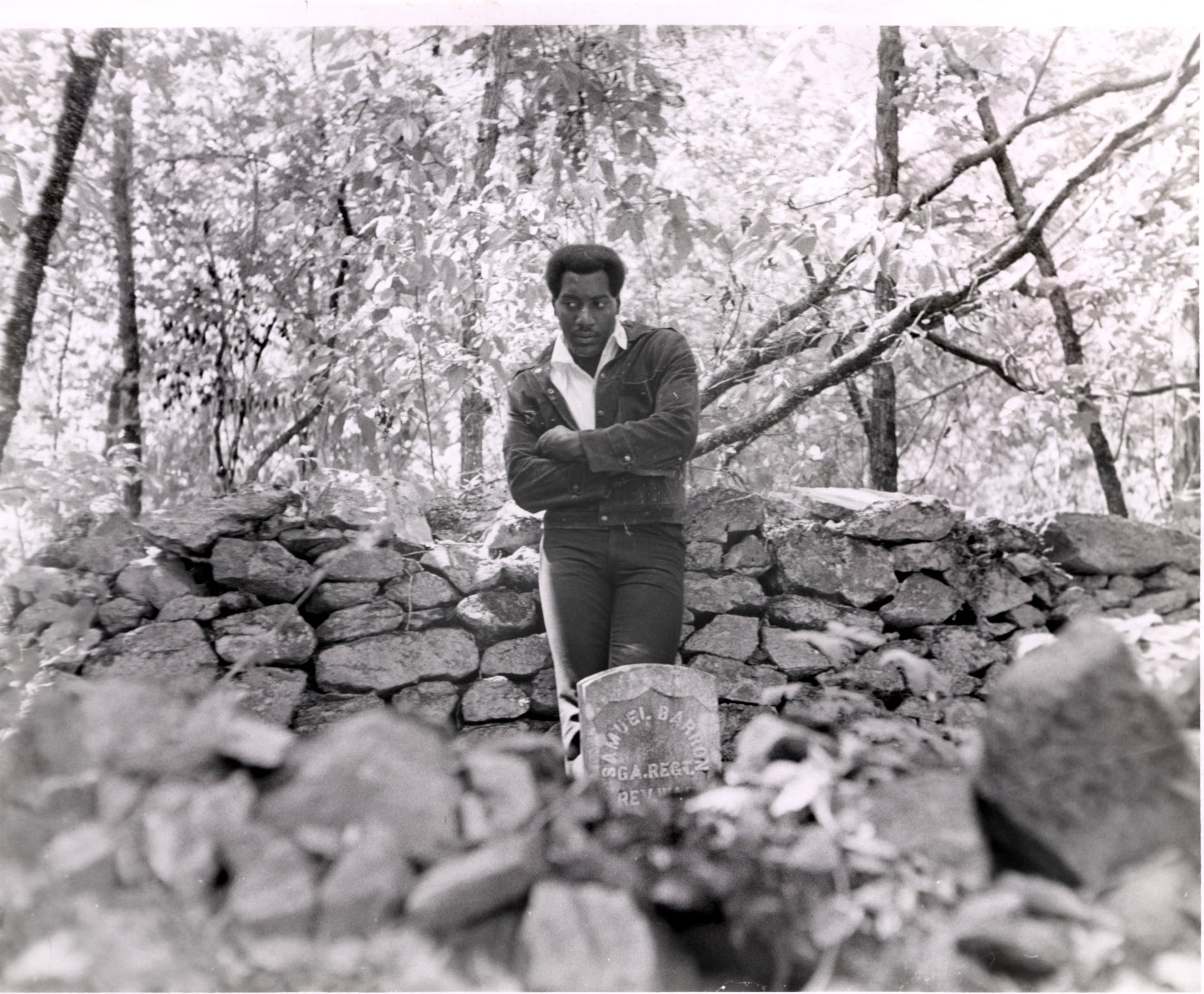

At one time, Redding was one of the largest African American landowners in Georgia. He had a 300-plus acre ranch in 1965 in Round Oak in Jones County.

At 6 feet 2 inches tall, he loved to farm and to just “be in the country, in the woods,” said Redding-Andrews. “He was more than just a musician.” He loved to fish and hunt and loved to swim.

At his home, the Big O Ranch, he had a huge, “O”-shaped, 90,000-gallon pool built. At different times, he owned two planes and had his pilot’s license.

Redding had already built a solid reputation in R&B and soul circles. Gould said he was making between $2,000 and $3,000 a night with live performances, which was a lot in those days.

However, his big break with a crossover audience was at the Monterey Pop Festival in California in 1967.

Redding came out of Monterey bursting with confidence. As one who always took advantage of an opportunity, he used the success and confidence to improve his songwriting and his approach to his music, Gould said.

“He had this enormous triumph and six months later he was dead,” said Gould. “That’s the crux of the whole tragedy of it.”

On Dec. 10, 1967, Redding and members of the Bar-Kays were traveling to Madison, Wisconsin from Cleveland, Ohio in a twin-engine Beechcraft when it crashed into icy Lake Monona. Redding, just 26 years old, had recently bought the plane.

» RELATED: The rich Gullah-Geechee history of "Kumbaya"

All on-board, except Ben Cauley, a trumpet player for Bar-Kays, perished. Another band member, James Alexander, was supposed to be on that flight, but there wasn’t enough room so he took a commercial flight.

The crash happened just a few days after Redding recorded “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” and it became the music industry’s first No. 1 posthumous record, said Gould. It won two Grammys. Redding would later be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1989, the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1994 and receive a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999.

Redding-Andrews used to feel that, with her father’s death, his notoriety would diminish. However, once she got to college, people would get excited when they found out she was Otis Redding’s daughter.

» MORE: Aretha Franklin's civil rights legacy

Redding-Andrews would often tell them, “My Dad is a big deal, but he is not Elvis. And people would respond, ‘But he is a bigger deal than Elvis.’”

Today, a life-size bronze statue of the famous singer overlooks the Ocmulgee River, near the Otis Redding Memorial Bridge.

His two sons, Otis Redding III and Dexter, are musicians. They used to perform as The Reddings.

“I don’t like to say I followed his footsteps because not very many people can do that,” said Otis III. “We chose our own path. It takes a lot of nerve to do what I do. I have my own twist. I don’t try to sing like him or dance like him. That’s not going to happen. Dad had such a vocal range and style that no one tries to emulate him.”

But, while Otis Redding is remembered for the music, Redding-Andrews hopes people also remember that he always encouraged young people to get a good education and to really understand the music business if they wanted to build careers in it.

“He took time to learn his business so he could really call his own shots,” she said. He also provided scholarship to youths from poor communities.

Her father was thorough in whatever he did, she said.

Before he died, Redding was in the midst of recording new songs and taking his music in a different direction.

He had been listening intently to the Beatles’ latest release, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” The album was considered a breakthrough in the world of music.

“The new songs he was writing took all the musical power of his early music and the rhythmic and emotional intensity and applied it to more sophisticated lyrics and more sophisticated ideas of what a song could be,” Gould said.

What if he hadn’t died on that cold Sunday afternoon?

» MORE: W.C. Handy: How musician became "Father of the Blues"

“Otis would have done what Marvin and Stevie did do,” said Gould. “He would have been the first of those R&B performers and songwriters to make the transition from putting out singles to putting out albums. Artists were finally freeing themselves from the conventions of R&B being only on radio.”

Redding-Andrews listens to her father’s music all the time. Sometimes, when she’s doing so, she grows quiet and becomes contemplative.

“I really try to analyze what he was thinking when he was singing those songs,” she said. If she could talk with her dad today, she said, she would ask him “What will you write next to unify this world? So many of his songs did.”

Throughout February, we’ll spotlight a different African American pioneer in the Living section every day except Fridays. The stories will run in the Metro section on that day.

Go to https://www.ajc.com/black-history-month/ for more subscriber exclusives on people, places and organizations that have changed the world and to see videos and listen to Spotify playlists on featured African American pioneers.