COLUMBUS — Nick Norwood recently led a visitor inside Carson McCullers’ childhood home for a tour of its newly completed renovation, a major overhaul costing about $200,000.

Built in 1919 and now operating as a museum by appointment, the famous writer’s house has been repainted inside and out. The original hardwood floors have been refinished and the kitchen has been upgraded with new cabinet doors and granite countertops. Newly installed shutters keep the sunlight off McCullers’ precious belongings, now displayed in custom-made glass cases from Germany.

This is where she lived into her teenage years. Where she staged plays for her family, drafting her siblings as actors and transforming the pocket doors in their parlor into stage curtains. Where she came up with the idea for her first novel, “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.”

Six years after she moved away, McCullers published the book, an astonishing story set in the South with a wide and diverse cast of memorable characters yearning to connect with each other. It became a bestseller and made her famous. She was just 23.

McCullers went on to publish more stories, some of which were turned into films and plays, before she died after suffering from a massive stroke in 1967 at age 50.

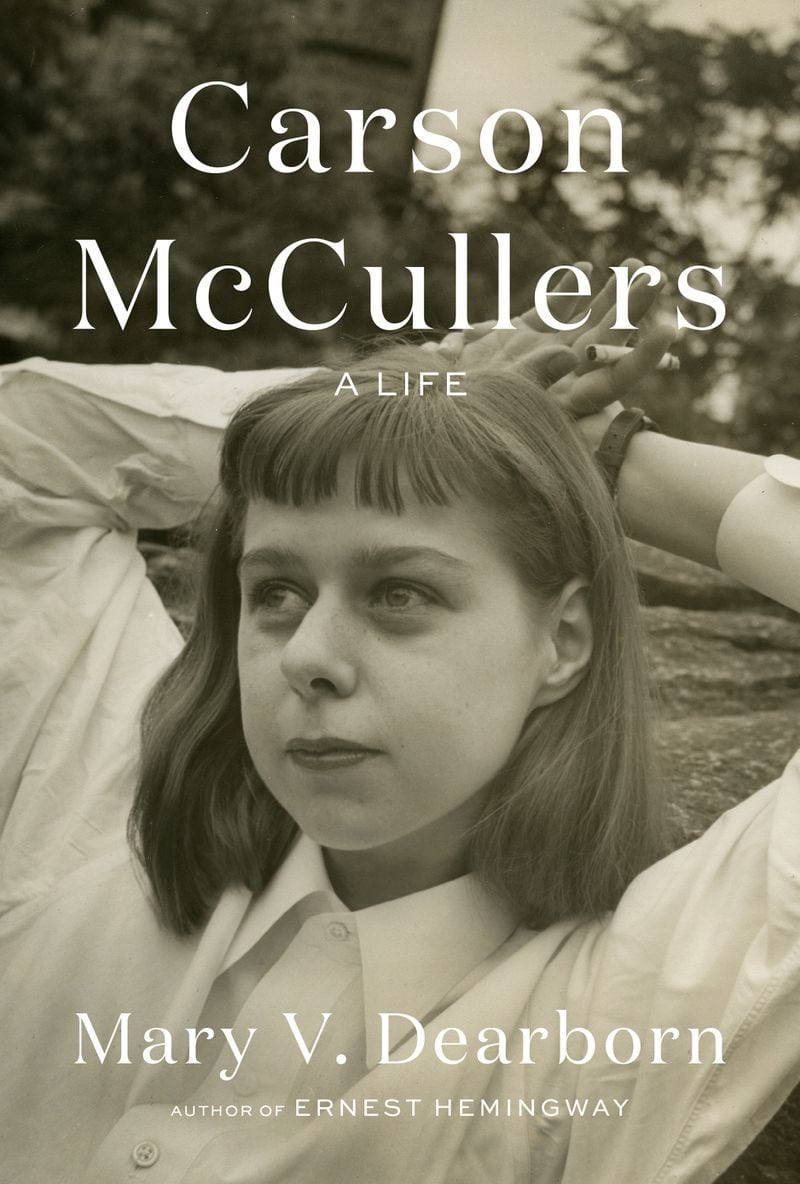

More than five decades later, McCullers is back in the spotlight with the renovation of her home on Stark Avenue and with a recently released biography by Mary Dearborn, a prolific writer known for her detailed portraits of Ernest Hemingway and Henry Miller.

A documentary about McCullers is scheduled to be released this year. A collection of her letters is due out next year. Meanwhile, her other home, in Nyack, New York, is set to undergo a $1.5 million renovation that will transform it into a destination for Columbus State University students, faculty and artists.

Norwood, who leads the university’s Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians, expects the fresh scrutiny will bring more readers to the author’s writing and what he calls her “radical empathy.”

McCullers, who endured serious mental and physical illnesses, wrote compassionately about disabled people and those experiencing poverty and racism. Bisexual, McCullers also wrote movingly about how love can surface in myriad ways. Among her most famous characters are a pair of deaf men in a tender relationship and a solitary, slightly cross-eyed giant of a woman who loves a dwarf with a hunchback.

“I would love it if the rest of the world would realize this is a writer we should be paying more attention to because what she did and how she did it are right in the middle of lots of conversations that we are having in the culture right now,” said Norwood, a poet who teaches creative writing at Columbus State University.

Credit: Knopf

Credit: Knopf

‘All the love you can use’

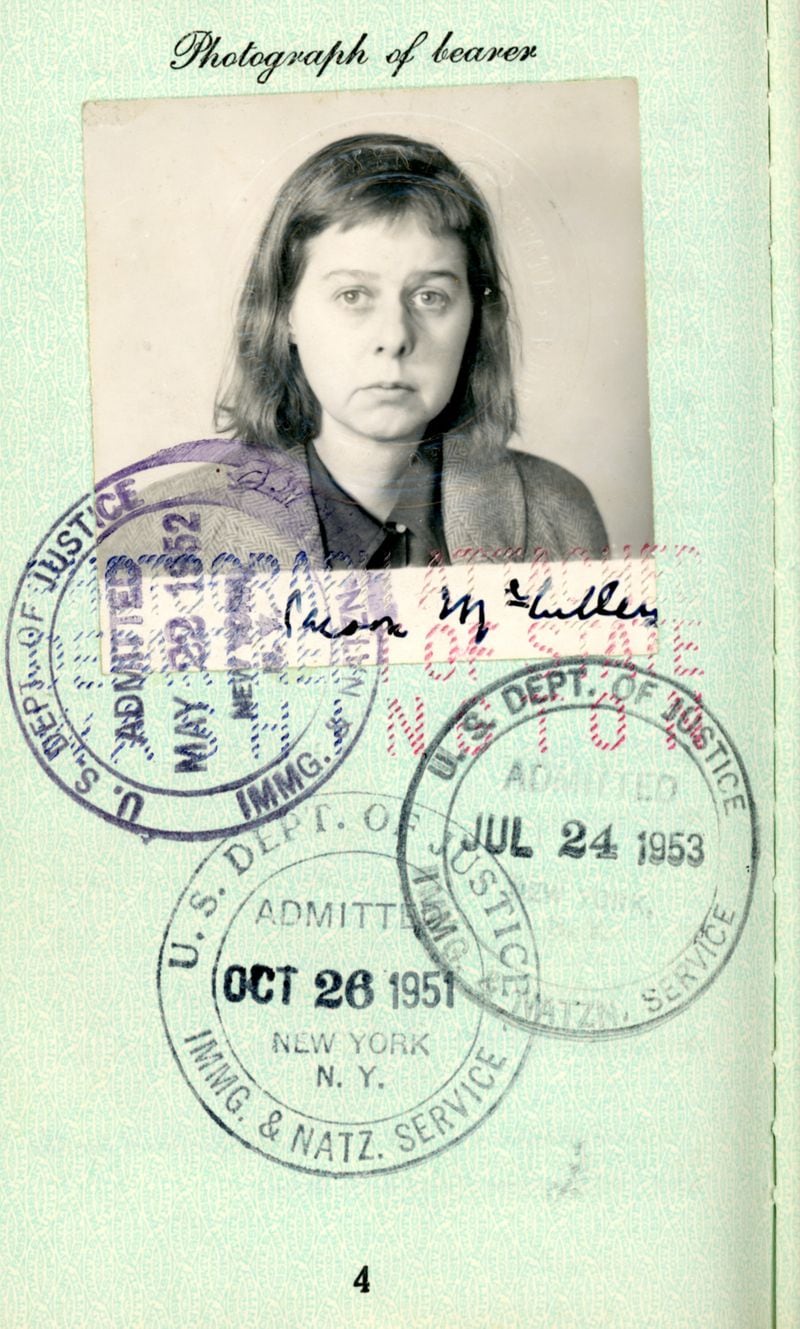

The oldest of three children, Lula Carson Smith was born in Columbus, which became the backdrop for her stories. Her parents worked in the jewelry industry. Strongly encouraged by her mother, McCullers took piano lessons and dreamed of becoming a composer.

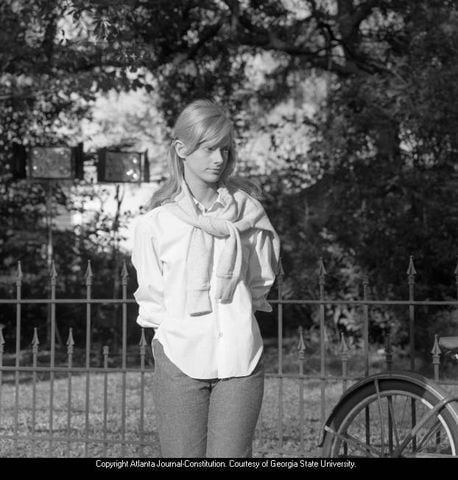

At 15, McCullers dropped “Lula” and went instead by her androgynous middle name, Carson. As an adolescent, Dearborn wrote in “Carson McCullers: A Life” (Knopf, $40), the author mostly dressed like a boy, finding that more comfortable. Later, she favored tailored men’s white shirts. She repeatedly fell in love with older women.

Eventually, McCullers decided to become a writer instead of a professional musician. She read voraciously from an early age, devouring the works of the Russian writers Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov.

She moved to New York City, where she studied fiction writing at Columbia University. She shared a home in Brooklyn Heights with the writers W.H. Auden, Richard Wright and Paul Bowles. And she befriended playwright Tennessee Williams.

Toward the end of her life, according to Dearborn, McCullers concluded she had become a “well-known fixture on the literary scene when she was too young to know what she was doing.”

“I was a bit of a holy terror,” McCullers once said.

Dearborn’s biography explores McCullers’ excessive drinking, the alcoholism that ran in her family, her suicide attempt, her weekslong stay at a psychiatric clinic, her medical abortion and her stormy relationship with her husband, Reeves McCullers, a World War II combat veteran who ultimately took his own life. Carson McCullers could be self-centered, needy and difficult.

Some of her behavior undoubtedly stemmed from her fragile health. McCullers suffered from rheumatic fever as a teenager, an illness that was misdiagnosed and untreated and that caused rheumatic heart disease. She experienced a series of strokes, which caused her severe pain and paralysis. At times, she was bedridden.

“Beneath illness and alcoholism, however, was a remarkably resilient and uncannily talented artist who proceeded as if she were on a mission to make sense of her existence and express it in her work,” Dearborn wrote. “In the process, she created what may be American literature’s most detailed, carefully observed picture of what it means to be an outsider.”

Carlos Dews, an expert on McCullers, is editing a selection of about 1,000 of her letters that he expects to publish in fall 2025. Gathered from collections around the world over the past 15 years, her letters illuminate the business side of her writing, her spirituality and her unrequited love, said Dews, who has named his book after a salutation McCullers wrote in some of her letters: “All the Love You Can Use.”

“There are quite a few love letters in the collection,” said Dews, who teaches at John Cabot University in Italy. “They are very emotional but also heartbreaking because almost all of the love she expressed in her life was not reciprocated. A lot of them are sort of tragic, one-sided love letters.”

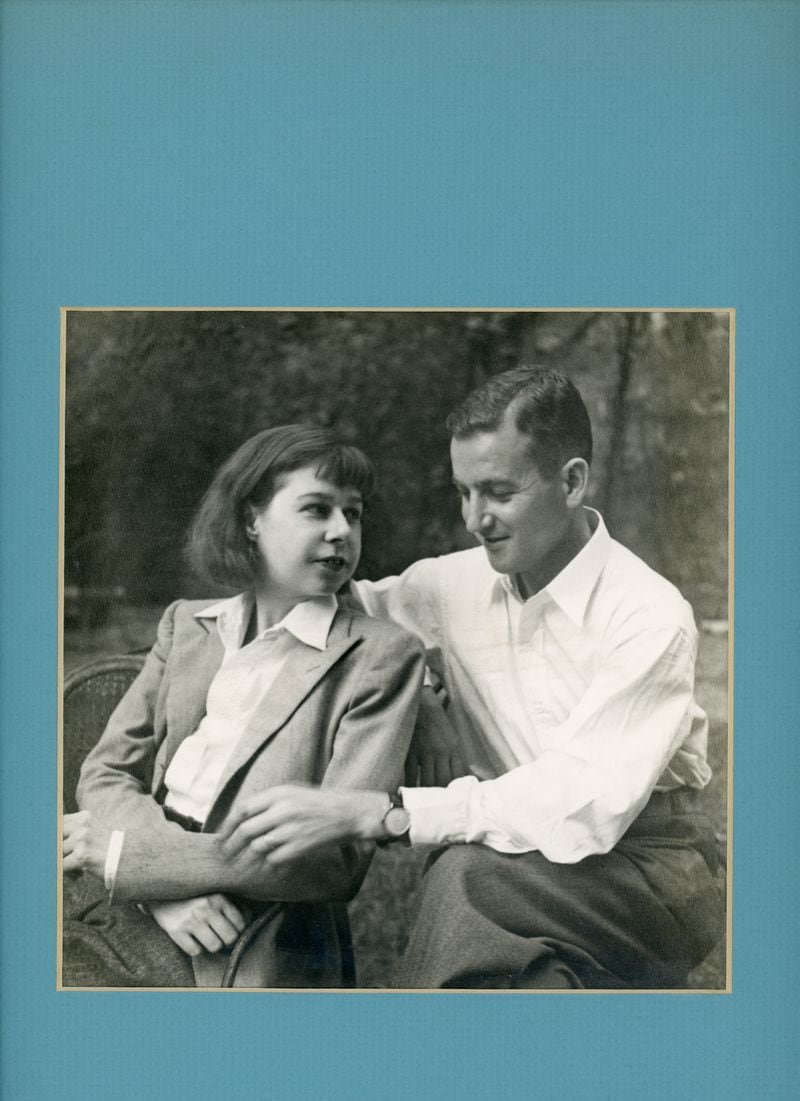

Credit: Dr. Mary E. Mercer/Carson McCullers Collection, Columbus State University Archives and Special Collections

Credit: Dr. Mary E. Mercer/Carson McCullers Collection, Columbus State University Archives and Special Collections

Wunderkind

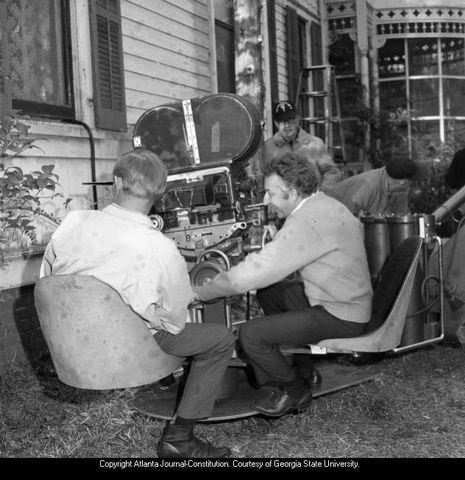

Claudia Müller, an award-winning filmmaker who is based in Berlin and known for her documentaries focusing on female artists, learned about McCullers from a friend, who recommended she read “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.” Müller was struck by the compassion in McCullers’ writing and decided to coproduce a documentary about her with the Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians.

With the support of the center and another coproducer, the European television channel ARTE, Müller filmed in Columbus and at Fort Moore last year. Previously called Fort Benning, the military post appears to be the setting for McCullers’ strange and mesmerizing story, “Reflections in a Golden Eye.”

Müller has named her documentary “Wunderkind,” based on the semiautobiographical short story McCullers wrote about a teenage musical prodigy. McCullers published it in Story magazine in 1936, when she was 19. Müller expects her documentary to air in Europe this fall and hopes for it to appear in the United States afterward.

“My aim was just to make her more known and share my passion and make people read Carson McCullers again,” Müller said. “For me, she was visionary because she brought up themes which are now in discussion.”

For her documentary, Müller interviewed Dews, Dearborn and Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega, who has been inspired by McCullers’ writing. In the film, Vega appears in McCullers’ home in Nyack, New York, reading from a famous passage about love from McCullers’ “The Ballad of the Sad Café.”

In part, the passage reads: “There are the lover and the beloved, but these two come from different countries. Often the beloved is only a stimulus for all the stored-up love which has lain quiet within the lover for a long time hitherto. And somehow every lover knows this. He feels in his soul that his love is a solitary thing. He comes to know a new strange loneliness and it is this knowledge which makes him suffer.”

Vega, who has written songs and a play based on McCullers and her writing, is gratified McCullers is getting renewed attention.

“I hope people acquaint themselves with her. There is so much there to unpack. She was such a rebel in a way,” Vega said. “I am looking forward to hearing what people have to say about her work.”

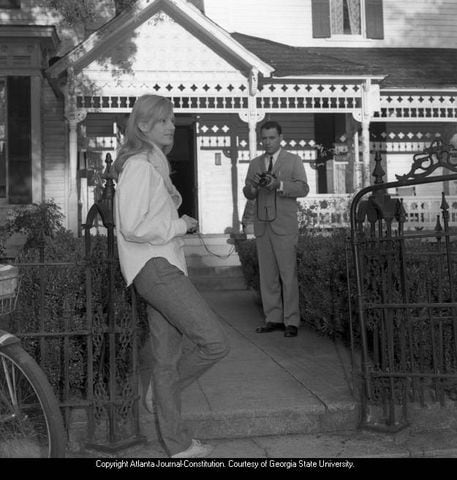

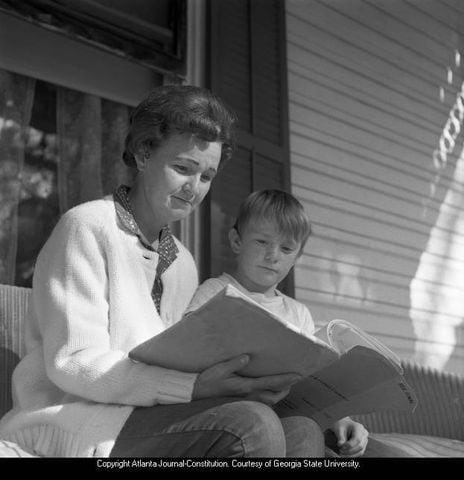

Credit: : Dr. Mary E. Mercer/Carson McCullers Collection, Columbus State University Archives and Special Collections

Credit: : Dr. Mary E. Mercer/Carson McCullers Collection, Columbus State University Archives and Special Collections

Weeping in McCullers’ bedroom

McCullers often wrote discerningly about children, which helps explain why some readers bond with her work when they are young, said Norwood, who counts himself among such fans. Her admirers trek from all over the world to Columbus so they can visit her home on Stark Avenue.

Inside, they can see her high school senior yearbook photo, her last typewriter, the cane she used and the artwork she collected, including an original dry point by James McNeill Whistler. The home also features a chair Marilyn Monroe once sat in during a visit with McCullers.

The bedroom McCullers shared with her younger sister, Rita, is where the author worked on her novel, “The Member of the Wedding,” which she later adapted into a prize-winning Broadway play. Some visitors weep when they step inside the room, Norwood said. He recalled one woman in particular who was visiting from Spain.

“She came to America to do some things, but specifically she wanted to come here because Carson McCullers was her favorite writer,” Norwood said. “And she was overwhelmed. She kept apologizing to me. She said to me, ‘She just means so much to me.’”

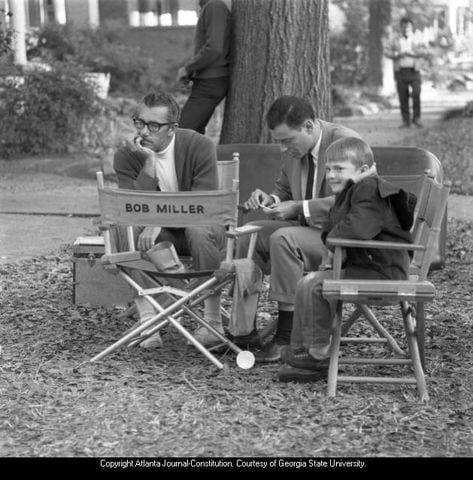

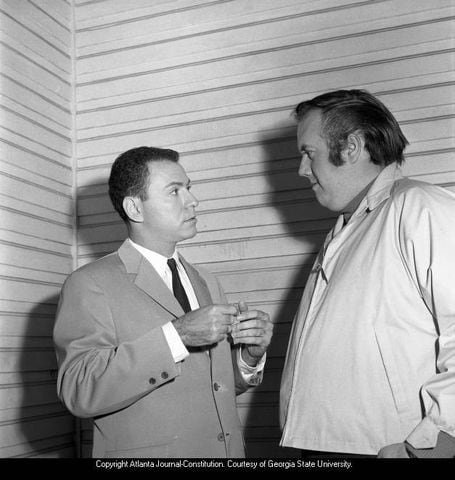

Credit: Carson McCullers Center

Credit: Carson McCullers Center

Museum tour

Carson McCullers’ House. 1519 Stark Ave., Columbus. Free, by appointment only. To schedule, email mccullerscenter@columbusstate.edu or call 706-565-1200. mccullerscenter.org

Author events

Mary Dearborn. Presented by the Georgia Center for the Book. 7 p.m. April 22. Free. Decatur Library, 215 Sycamore St., Decatur. georgiacenterforthebook.org. Also 6:30 p.m. April 23. Free. Columbus Public Library, 3000 Macon Road, Columbus. cvlga.org