It was a week after the presidential election and the maelstrom had descended upon Georgia, now the epicenter of insanity.

The state’s two U.S. senators had folded to Trumpian pressure and called for Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to resign, a tedious recount of paper ballots was underway, and the airwaves and “interwebs” were beset by desperate, angry and increasingly nutty conspiracies.

I sent a message to Georgia elections director Chris Harvey (our kids went to school together) to say placid days hopefully lay ahead.

“I think I’m about to go back to doing something more fun,” he responded. “Like solving murders.”

Harvey, a former cop and homicide detective who helped solve a shocking December 2000 election-related murder, knows the satisfaction of bringing justice in the wake of terrible crimes. But delivering a fair election in the face of Donald Trump and his flying monkeys just hasn’t afforded him that same sense of accomplishment.

“People ask the difference between working homicides and elections,” he later told me. “In homicide, you occasionally come across remorse.”

It was well-known that Raffensperger was under constant guard because of numerous threats, as was Gabriel Sterling, the GOP operative hired to be the secretary of state’s Igor. (Sterling is the guy who famously fired back at the vermin making such threats.)

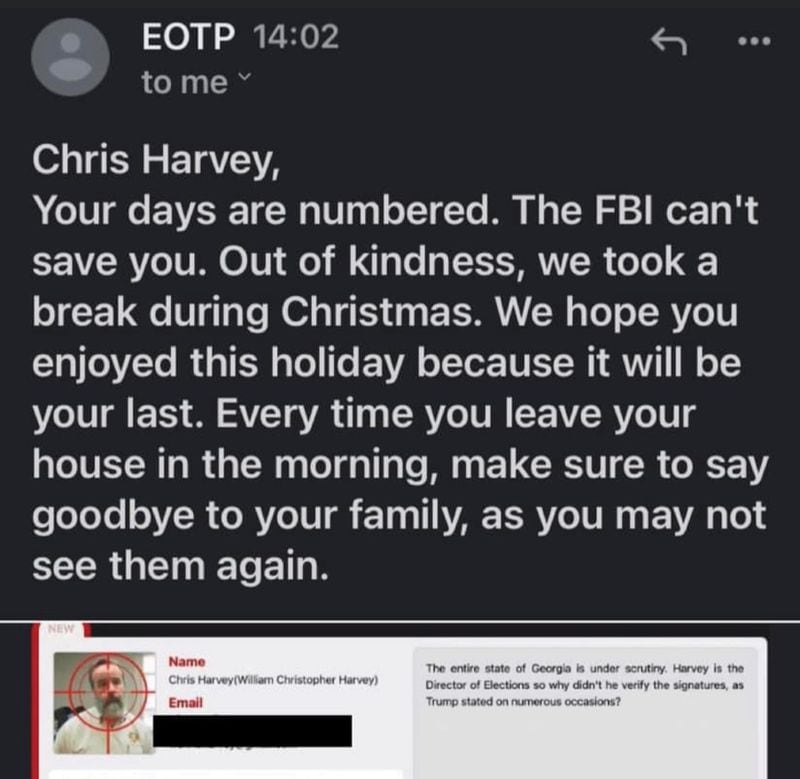

Harvey, a quiet, more behind-the-scenes fellow, did not escape the madness. On Jan. 4, the day before Georgia’s runoff election for two U.S. senators, someone emailed him a threat taken from the so-called “Dark Web.”

Credit: Chris Harvey

Credit: Chris Harvey

It included a photo of Harvey targeted in a rifle scope image, a photo of Harvey’s home, plus his address and email.

And there was a friendly note: “Chris Harvey, Your days are numbered. The FBI can’t save you. Out of kindness, we took a break during Christmas. We hope you enjoyed this holiday because it will be your last. Every time you leave your house in the morning, make sure to say goodbye to your family, as you may not see them again.”

On Facebook, he quipped that the photo on the Web let the “extremist nut-jobs” know that his house needed a paint job.

Again, the fact that the state elections director got a threat was not unthinkable. “I’m surprised that people were surprised by that,” he said. Even low-level election workers got ominous threats and were even followed by self-appointed guardians of freedom, people who got their marching orders from Q.

“I wasn’t incredibly worried about it, although I didn’t want to see my house and address online on the Dark Web,” he said. “My concern was that some of these sympathizers would decide to become a hero. You put a lot of targets out there and (someone might) try to prove they’re a ‘real American.’”

The cretin who posted the threat to Harvey was probably some sad, underachieving twerp who was angry about his own shortcomings. But it’s a time when many unstable, conspiracy-spewing buffoons are calling themselves patriots and going all 18th century, talking about hanging public officials and the “blood of traitors.”

Hell, we’re liable to elect someone like that.

But the cold-bloodedness of politics spiraling into actual bloodshed is nothing new to Harvey. Remember, almost 20 years ago he was in the middle of an infamous murder case precipitated by an election result that enraged someone.

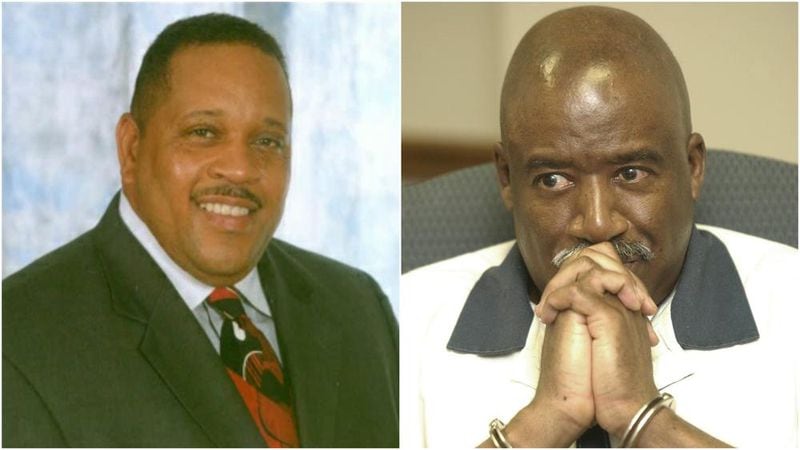

That was the December 2000 murder of Derwin Brown, who after a bitter campaign defeated DeKalb County Sheriff Sidney Dorsey, a man who did not take defeat well.

“In some cases, elections are life and death,” said Harvey. “Twenty years ago, it resulted in a death and upended the county. And here we are again. It’s come full circle.”

In 2000, DeKalb District Attorney J. Tom Morgan was investigating Dorsey for corruption. Dorsey lost the runoff election to Brown. And three days before Brown was to be inaugurated, he was shot 11 times outside his home.

Morgan immediately put Harvey — then a DA investigator who’d once studied in a seminary to be a Catholic priest — in charge of his office’s investigation. Harvey worked daily with the DA and a host of other agencies to unravel a desperate and astounding murder conspiracy.

Credit: Rodney Ho

Credit: Rodney Ho

In late 2001, as investigators closed in on Dorsey’s murder crew, Morgan was given some startling information: A hit list had been compiled by the former sheriff and his goons. And the DA’s name was on it.

For weeks, Harvey and Morgan worked side by side, both armed with guns and clad in bulletproof vests. The investigator picked up the DA each morning at his home and often delivered him back late at night.

The worry about Morgan getting bumped off was legit, Harvey said. “When you look at the brazenness of the crime, how could you not?”

Harvey was involved in a six-hour interrogation of Patrick Cuffy, Dorsey’s enforcer and a mastermind of the killing. It was the link that brought down Dorsey, who was later found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Cuffy spilled out an incredible plot to Harvey, telling him that he and another conspirator tried to buy high-powered semiautomatic rifles before the murder. But that deal fell through when the guns’ owner grew suspicious and refused to sell the weapons because the insistent buyers claimed they were to be used in a Boy Scouts program.

Harvey later went to work for the Fulton County district attorney’s office and then the secretary of state’s office, initially as an investigator.

Harvey, a devout Catholic, a Citadel grad, a conservative and a family man, is about as straight an arrow as you’ll ever meet.

“If Chris is in charge of an election, I have no question of its validity,” Morgan said.

Harvey simply sees himself as a “referee in a white hat,” adding, “The facts are the facts. You can’t pick a case to get behind that there was fraud.”

Still, the twisted rhetoric spewed by otherwise “normal” Republicans — including many in the Legislature — has fanned the flames of ignorance that’ve hit close to home for Harvey. He said he has friends at St. Thomas More (the parish where he and I sent our kids to school) who’ve shunned him because they think he’s “part of it.”

You know, part of “The Steal.”

Harvey expects the vitriol to swell again next year in the state elections and has concerns that legislators will do too much this year to limit how people vote. The GOP has a host of bills that could eliminate no-excuse absentee voting, ditch the ballot drop boxes, and impose tougher ID requirements.

“I hope they don’t worry that too many people are voting,” he said.

They are worrying EXACTLY that.

Harvey looks back proudly at having had a part in solving the Dorsey case, although during the hectic days of long ago, he thought he’d never cherish such memories.

“At some point, I’ll look back and say, ‘I’m glad I went through it,’” he said of the 2020 election. “But right now, I’m not there yet.”