If she had graduated from the University of Georgia this year, Wendy Hsiao would likely have been fending off a flock of would-be employers, picking among offers until she found what fit her best.

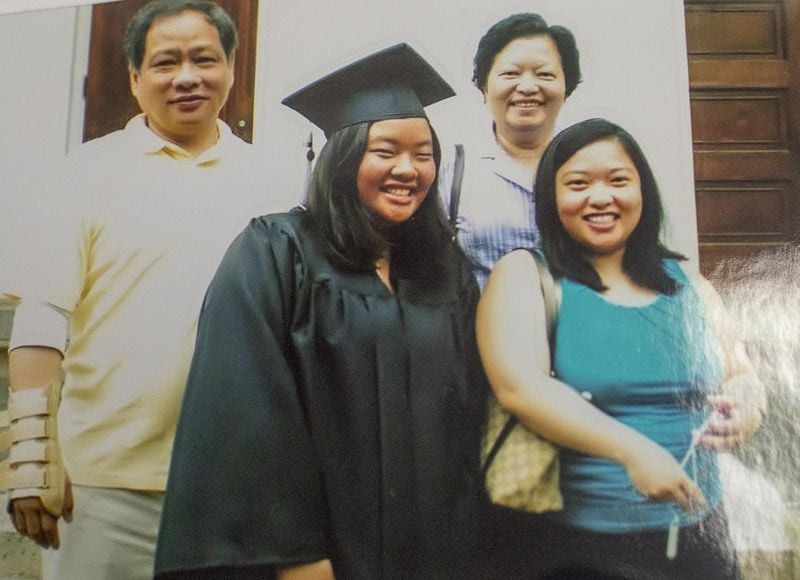

After all, she had been named to the Dean's List, worked seven internships and spoke at her class convocation ceremony. She was aggressive too, applying for about 100 jobs. Yet she received just one response, a small public relations agency offering a part-time slot, Hsiao said. "It was really disheartening. It was like 'What's the point?' if no one's going to hire me."

Her timing couldn't have been worse.

Caroline Cusick graduated from Georgia Tech's Scheller College of Business with a degree in business administration. The 22-year-old said she received multiple job offers and took a job with a global consulting company. "Almost all of my friends knew what job they would have by last November. I don't know one person who is graduating this year who doesn't have a job."

Her timing couldn’t have been better.

Hsiao graduated in 2009, when unemployment was heading for double digits, many companies were failing and the economy was floundering.

Cusick graduated this May as new job seekers waltz into a labor market with a jobless rate at just 3.0% in metro Atlanta after several years of economic growth.

Since May 2009, the metro Atlanta economy has added more than 500,000 jobs. That steady expansion has been good for white collar, but also for blue.

Good enough to convince employers to consider workers they might have disdained in the past.

Nicholas Holmes, 39, came into construction after a troubled childhood and errant adulthood that included about seven years in jail. Many ex-offenders struggle to find work, but he found that an improving job market — and some training programs — help.

His timing was good, too: He was turning his life around just as the economy was really heating up. Five years ago, Holmes landed a job installing floors, walls and ceilings.

“I am a skilled tradesman now, not just a joe walking in off the street.”

He has moved up to foreman, a job that, with experience and overtime, can put a worker in six figures, he said. “And I’m getting there.”

‘Floors of empty desks’

In the past 12 months, metro Atlanta has added more than 50,000 jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In contrast, the class of 2009 snagged their diplomas after 12 months in which Atlanta lost 148,000 jobs – and that was just a drop in the national hemorrhage.

The Great Recession was particularly tough on young people trying to enter the job market for the first time. The jobless rate for Americans 20 to 24 years old spiked to 15% in 2009, more than double what it is now.

Ben Stowers, now 33, recalls it as a trying time. His father had a small real estate business and helped him arrange some hard-to-get interviews in 2009 after he graduated from the University of Georgia.

“They literally said, ‘We can hire you, but we can’t pay you anything,’” he said. “These are some of the biggest real estate companies in the world with offices in Atlanta, and they would take me into their offices and give me a tour. It was just floors of empty desks.”

And it's not just what recessions do right away to job prospects. Studies show that graduating into a recession can undercut incomes and damage careers for years. Some people became so discouraged they stopped looking, which meant they weren't even counted as unemployed. Others took low-paying jobs for which they were overqualified.

It can take a full decade for college graduates to climb back to the income they would have had, according to a study by a University of Rochester economist. From 2009 through 2014, the median weekly pay of workers grew an average of 1.5% a year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since then, they have averaged about 3% a year.

Many graduates who faced a bad job market moved in with their parents or returned to school.

Jenny Jang did both. She had planned to teach after earning a degree in early childhood education in 2009 from Kennesaw State University. The only job offer she received was for something that didn't match her qualifications.

So she decided to get a masters in higher education.

Jang, 32, never went back to teaching. “I got a part-time job at a start-up company where I had to translate a web site, from English into Korean,” she said.

Eventually, they hired her full-time, she said. “That is how I jumped into marketing.”

Perhaps more than anything else, a recession means a shift in trajectory.

His senior year at Emory University, Matt Kelsey and his fiancé were planning to settle in Atlanta so the couple could be near her family.

It didn’t work out.

He couldn’t land a job in Atlanta. He got an offer in Tampa. He took it. They moved south.

Ten years later, they’ve done fine, but it is not what he and his now-wife had envisioned. Kelsey, 33, is now a team leader at pharmaceutical giant Bristol Myers-Squibb in New Jersey. “If I had graduated at a time when the economy was booming, I would definitely be in Atlanta.”

Jordan Pious, 32, another Emory graduate that year, thought he had it made. He had plenty of interviews and job offers, while some of his friends had neither. Some of those friends would go a year or more without work.

“It was definitely a tough time,” he said. “There weren’t enough jobs for everybody graduating with your degree. You really had to step up your game.”

But by the fall of 2008, he had taken a job offer with a consulting company.

“Then, two months before graduation, they called and said, ‘We are delaying the start date. To September.’”

Pious scrambled and found freelance work with a professor he knew. A few months later, the company called again: the job was delayed until January.

Hiding ‘interview’ suit, landing full-time job

Back in 2009, even the graduates with jobs knew how bad things were.

Bhavik Trivedi, 33, graduated from Georgia Tech’s Scheller College in 2009. He had several offers in the months before commencement and eventually chose a position at Deloitte.

But he wasn’t oblivious: He felt uncomfortable wearing his “interview suit” around people who couldn’t even get their applications acknowledged.

“In my group, we finally stopped wearing suits to class,” Trivedi said. “We kept our suits in the career center. Because you don’t want to rub it in anyone’s face that you’re getting a job.”

Slowly and fitfully, the economy improved. Layoffs ebbed and job growth resumed. Looking back, the contrast is stark, said Jamon Williams, a Labor Department official who was a supervisor in a career center in 2009.

“Now, companies are having trouble finding people,” he said. “That’s the biggest difference. I think the young workers definitely can choose where they want to work. Back then, you had to take what was left – if there was anything left.”

Now, millions of baby boomers are retiring and continued growth means that when it comes to fresh labor, it's a seller's market, said Zach Fields, vice president of the Construction Education Foundation of Georgia, which promotes learning about trade in schools.

“The industry is so short” on construction workers, he said. “Those young people are being fast-tracked into leadership positions if they show some aptitude and work ethic on the front end.”

For workers like Andrew Lamb, that spells opportunity. Lamb, 19, walked out of Kennesaw Mountain High School a year ago into a job as an apprentice in construction.

“I basically knew how to read a tape measure and that was it,” he said.

Lamb frames walls and ceilings as the buildings go up. And they are going up so fast in Atlanta, that he doesn’t fret about demand for his skills, he said. “I was in Chick-fil-A one day, and two different guys saw my vest and offered me jobs.”

For Hsiao, the 2009 graduate, the long days working internships and late nights proved fruitful eventually. She found her footing with a large PR firm in Los Angeles that offered her a job about four months after graduation. She returned to Atlanta a year later.

Hsiao, 32, now works as an account director at Hope Beckham Inc., a prominent Atlanta firm. The small company where she first found work no longer exists.

“I think I’m exactly where I should be right now,” Hsiao said.

Georgia, share of workers in the workforce, May

1999: 69.5%

2004: 67.5%

2009: 65.8%

2014: 62.0%

2019: *62.6%

*Most recent data available

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Current average starting salary for college graduates

United States: $51,347

Atlanta: $50,577

Source: Korn Ferry