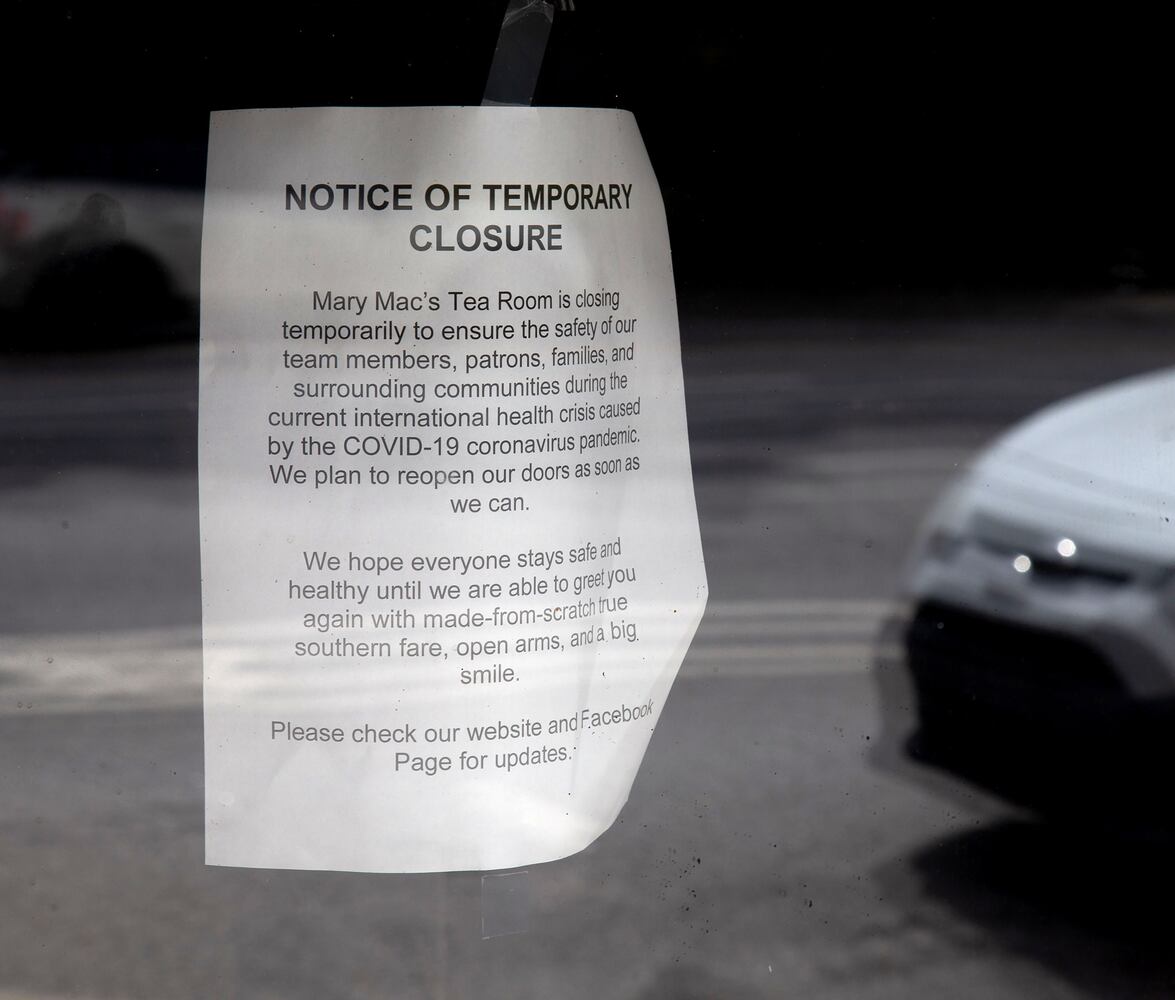

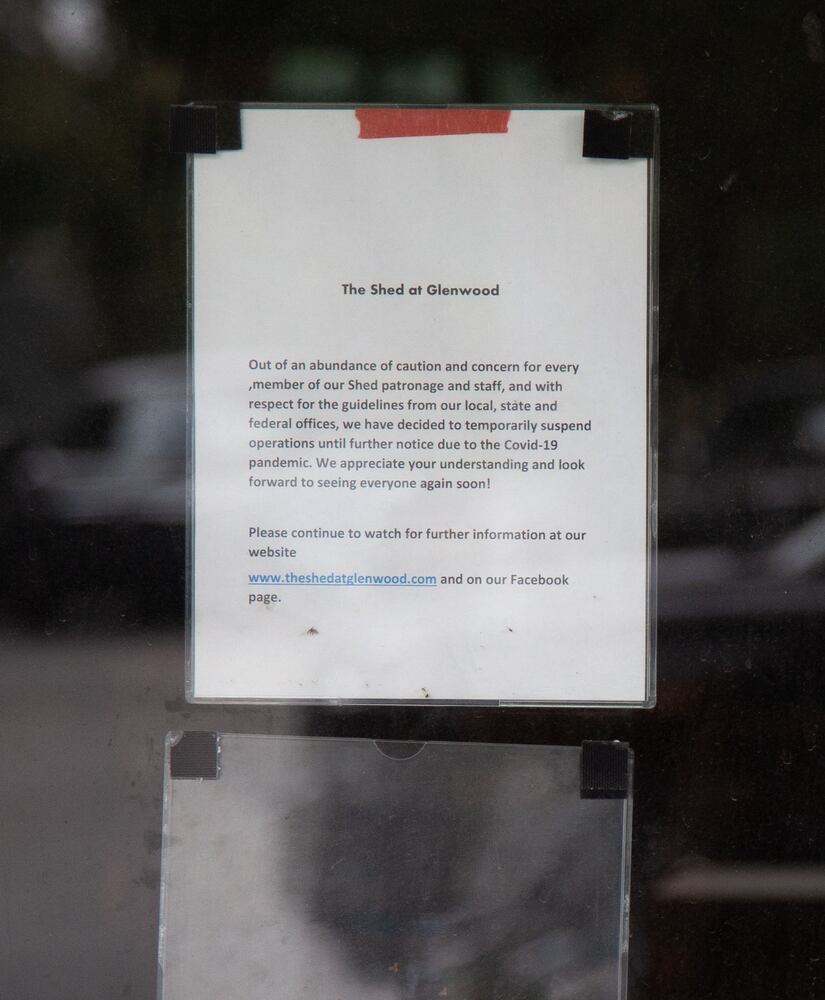

Georgia Grille in Buckhead. Noble Fin in Peachtree Corners. The Shed at Glenwood. Bone Lick Southern Kitchen in Old Fourth Ward. Mary Mac’s in Midtown.

These are just a few of the metro Atlanta restaurants that make up the 100,000 food and drink establishments across the country whose permanent or long-term closure is tied to the coronavirus.

As the pain continues, restaurant operators are pushing for government help to stay afloat.

Six months following the first shutdown of restaurants due to the pandemic, the restaurant industry is nowhere near recovery. According to a survey recently released by the National Restaurant Association, nearly 1 in 6 restaurants is closed either permanently or long term. The figure is in stark contrast to the 50,000 restaurants that close on average annually, based on U.S. census data.

Credit: Yvonne Zusel

Credit: Yvonne Zusel

For restaurants still in operation, the outlook is not good. Of the roughly 3,800 Georgia operators who completed the National Restaurant Association survey, 87% report lower total dollar sales volume in August compared to the same period in 2019, overall sales down 30% on average compared to prior years.

Independently owned restaurants are especially at high risk of being a casualty to the pandemic. This spring, some operators formed the Independent Restaurant Coalition to speak as a united voice urging Congress to pass the Restaurants Act of 2020 to establish a $120 billion revitalization fund for the industry.

On Friday, National Restaurant Association board chair and Louisiana restaurateur Melvin Rodrigue stood before the House Ways and Means Committee to urge Congress to take action before adjourning until November.

“If Congress adjourns without extending the Paycheck Protection Program or providing other enhanced relief, more restaurants will close, more employees will lose their jobs and the pandemic economic crisis will deepen,” Rodrigue testified. “What restaurants and their employees need is targeted help for the nation’s second-largest private sector employer.”

Georgia Restaurant Association CEO Karen Bremer voiced similar sentiments. “The time is now for government to step in to assist these restaurants that are the backbone of our communities," Bremer said Friday. "The restaurant industry provides many avenues for success for many people in our country by providing entry-level jobs, a pathway to leadership for minorities and other disenfranchised groups.”

“The number of restaurants and other small businesses being forced to close their doors forever is alarming," said U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson, D-Ga. “It is beyond time for the Senate to work with the House to pass legislation replenishing the Paycheck Protection Program and making it more flexible so that small businesses have more ability to pay other expenses while maintaining loan forgivable status.”

Like Johnson, the National Restaurant Association has also called on Congress to consider short-term assistance by authorizing another round of the PPP, and this time with greater flexibility in how the funds get used to cover operating expenses and payroll.

Traditionally, restaurants spend 36% of revenue on payroll and 30% on food and beverage. Fixed costs swallow up the rest, leaving operators an average of 4%-6% profit, according to Bremer. Should another round of PPP funding be authorized, the association wants operators to be able to apply a higher percentage of the loan toward fixed costs, especially as landlords come calling for rent money.

Credit: Mia Yakel

Credit: Mia Yakel

Zeb Stevenson, chef and co-owner of Redbird in west Midtown, agrees with the need for more flexibility with the way restaurant owners can allocate PPP money. “It can be used for payroll, occupancy and utility expenses. Those are great, big-line items, but there are so many more expenses in operating a restaurant,” he said.

Bruce Bogartz closed his Sandy Springs restaurant, Bogartz Food Artz, in August. Bogartz said that if the first round of the PPP had been structured differently and a second round had been authorized this summer, it might have given him a fighting chance.

Credit: Mia Yakel

Credit: Mia Yakel

Bogartz was among the many restaurants that shifted to takeout during the pandemic, but it wasn’t a sustainable business model for the less than 2-year-old eatery that relied on sit-down diners.

Even pizza joints are feeling the pain. “We are doing as OK as anybody can be right now,” said Jennifer Aton, co-owner of 1-year-old Junior’s Pizza in Summerhill. “Pizza is made for to-go. It’s not like other places where we had to drastically pivot. We just had to shut down our dining room. It’s not where we want to be. It could be worse.”

Takeout and delivery currently accounts for a higher portion of business for nearly 80% of Georgia restaurants compared to pre-pandemic days. Even for restaurants whose on-premises sales exceed those for carryout, factors such as dining room capacities and diner frequency are impacting the bottom line.

Credit: Mia Yakel

Credit: Mia Yakel

Takeout orders account for only between 12%-15% of sales at Redbird. But the majority of sit-down sales for a reduced capacity dining room and patio occurs on weekends. “Mondays through Thursdays are still very, very tough,” said Stevenson on Friday. “The books for tonight — I’m full. If you are interested in dining out and maintaining social distancing, come on a Tuesday when no one is around.”

At Noona Meat & Seafood in downtown Duluth, total sales are down 50% compared to prior years. Co-owners Michael Lo and George Yu said that the majority of their regular clientele is comfortable eating on-site and that, like Redbird, their Korean-inflected steakhouse does decent business Fridays and Saturdays. But because they reduced seating capacity by 50% as a safety precaution, on weekends alone, “we’re losing 50% of our sales,” said Yu.

Credit: Mia Yakel

Credit: Mia Yakel

“Weekdays were generally when casual friends and business associates would go out,” added Lo. “That’s what’s not happening. The weekday dining is definitely a lot lower. And everybody’s frequency: They are going out once a week where before, they might have gone out three times a week.”

Lo and Yu operate three other dining concepts, including Suzy Siu’s Baos, a stall at Krog Street Market. Even though counter-order concepts like Suzy Siu’s are ripe for takeout, traffic at the food hall is far from normal. “It’s still eerily empty,” said Yu. “Jeni’s Ice Cream used to have a line after lunch. Now, you see like one person. I think people are scared to be inside. It’s eerily creepy and different.”

- Staff writer Tia Mitchell contributed to this article.

BY THE NUMBERS

Based on a National Restaurant Association survey:

29% of Georgia operators say it is unlikely their restaurant will still be in business six months from now without government assistance.

38% of U.S. restaurants say they are unlikely to be in business six months from now if business conditions continue at current levels.

40% of restaurants across the country say they’re unlikely to be operating come spring if the federal government does not provide additional relief packages.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured