Charlotte Nash, Gwinnett County’s commission chairman, believes her residents are ready for more transit.

"We can't stop improving our road network," she said during her recent state of the county address, "but expanded transit options must also be part of any long-term solution."

Nash went on to say she wants the county to have a referendum on transit expansion in the relatively near future — probably not in 2017, but soon. And in the next 90 days or so, the county will launch a comprehensive transit study to determine what kind of options — heavy rail? light rail? expanded bus service? — might be most feasible.

In a county with a long history of reluctance to wade into the world of mass transit but an ever-evolving constituency, all of that begs several questions.

Would expanded transit in Gwinnett mean kismet or calamity? Would it be a necessary investment, congestion de-clogger and economic stimulus — or a misguided mission toward more taxes and a poorer quality of life? Would a vote even be successful?

Lawrenceville city manager Chuck Warbington says “it’s about time.” Many officials and residents from throughout the county hold similar beliefs.

But there are also folks like Melinda Snell Franklin.

“Folks that WANT expanded transit need to LIVE where they have it and quit moving out here and trying to drag it with them!!” the Snellville woman wrote on Facebook in response to a reporter’s inquiry. “NO THANK YOU!”

‘A pretty good job’

As it currently exists, Gwinnett County Transit consists of five local bus routes (only one of which operates on the weekend) and four express lines — three that leave park-and-rides near Lilburn, Lawrenceville and Buford and go to downtown Atlanta each morning before returning each evening; a fourth that starts in Atlanta in the morning and goes to Sugarloaf Mills mall and back; and a fifth that goes back and forth between Indian Trail Road andEmory University.

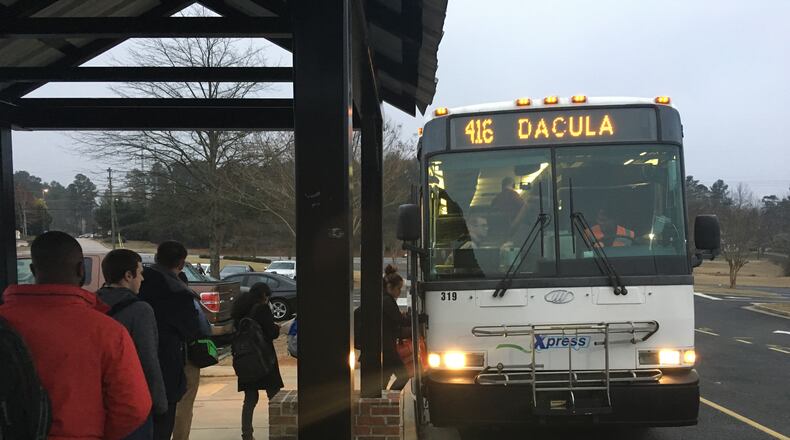

The Georgia Regional Transportation Authority also runs its own commuter bus routes to and from the county. Some go Downtown, others hit Midtown or the Buckhead area.

People like Doug Naville, a 45-year-old paralegal who takes a GRTA bus from Dacula to Atlanta every morning, think that’s enough.

“I think they do a pretty good job, absolutely,” Naville said on a misty recent morning at the bus stop.

But there are also folks like Anju Merycherian and Ann Kurian, biomedical researchers who ride the bus with Naville each morning because they don’t have driver’s licenses. They’d love more options.

“It’s really limited,” Merycherian, 25, said recently while waiting on their 7:30 a.m. departure. “This is the last bus, and if we miss it, then that’s it.”

In 2016, Gwinnett County Transit recorded a total of just under 1.5 million fares. That number includes more than 372,000 Express services fares (with each leg of a round trip counting as one fare), as well as nearly 1 million fares on local routes. The remaining 27,000 or so fares came from users of the county’s paratransit service, which serve residents with disabilities.

By way of comparison, MARTA saw an average of about 10.6 million bus and rail riders per month last year.

‘A lifetime ago’

Gwinnett voters first rejected MARTA expansion in 1971, then again in 1990.

But as Dacula Mayor Jimmy Wilbanks points out: “That was almost a lifetime ago in politics.”

While Gwinnett’s leadership has remained staunchly Republican and entirely white, the county has seen exponential growth in both size and diversity. In 1990, about 90 percent of the county’s 350,000 residents were white; more than half of the nearly 900,000 people that now call Gwinnett home are non-white.

The county, which is projected to be Georgia's most populous by 2040, narrowly voted for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump in November's presidential election. It was the first time it had chosen a Democrat since Jimmy Carter in 1976.

In 2012, Gwinnettians voted overwhelmingly against a regional transportation sales tax proposal that would’ve included seed money for unspecified transit options to link the county’s I-85 corridor to MARTA’s Doraville station.

But three years later, the Gwinnett Chamber of Commerce conducted a survey that found 63 percent of the county's likely voters were in favor of expanding MARTA into Gwinnett. About 50 percent were willing to pay a 1 percent sales tax to fund it.

The county itself is in the process of wrapping up a comprehensive transportation plan (a separate undertaking from the soon-to-launch study focusing solely on transit). Residents who completed surveys for the transportation plan listed "vehicular travel" as their top priority.

Transit service came in third, just behind “connectivity.”

‘We need to be realistic’

The long-term possibilities to be explored in Gwinnett’s upcoming study include “the development of high capacity dedicated right of way transit solutions,” meaning things like rail or bus rapid transit. The latter would operate in its own, dedicated lanes and likely have fewer stops than local bus service while connecting the county’s “activity centers.”

“I believe the county as a whole, if you ask the question, ‘Are you in favor of transit, do you want transit?’, I think the answer is probably overwhelmingly yes,” Gwinnett County Commissioner Jace Brooks said last week. Brooks’ District 1 covers much of the I-85 corridor, from the Duluth area to Sugar Hill.

“But when we get to the point of asking more specific questions … like, ‘Are you willing to raise your taxes essentially, one way or another?,’ I think you get different answers.”

Putting together the capital to launch a large transit expansion of any kind would be easy enough — it could theoretically be done through a 1-cent SPLOST like the one Gwinnett voters approved in November. But covering ongoing operation costs would be a more complicated undertaking.

Marsha Anderson Bomar is a Duluth city councilwoman and executive director of the Gwinnett Village Community Improvement District, which covers about 14 square miles along the I-85 corridor.

“I think we need to be realistic and look at what things costs,” she said. “And given the size of the county, we need to pick an option that we can afford to deploy somewhat broadly.”

About the Author