The opening scene of “My Monticello,” the titular novella of Jocelyn Nicole Johnson’s story collection, mirrors a moment in Charlottesville, Virginia, that much of America witnessed through television and computer screens: white men snarling, carrying weapons of resistance. In the photos, they are tiki torches; in the novella, they are rifles.

“White hands clutched metal canisters, swung torches spilling flames. Bright shouts, the rising haze of smoke — all that and more rousted us out. From our patchy front yards, we saw bodies blur as some of our neighbors charged forward to try to stop them.”

Thus begins the tale of a group of Black and brown neighbors who must work together to resist the machinations of a white supremacist mob bent on domination.

Da’Naisha Love, a young Black woman and the story’s protagonist, narrates the saga as survivors of the clash end up taking refuge in Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s former plantation set high on a hill above Charlottesville. Unknown to most in her group, Love is a descendant of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, one of the more than 600 enslaved people Jefferson once owned.

In Johnson’s lightly dystopian story, a reckoning happens — one where people of color reclaim the space, if just for a moment. Toward the end of the novella Love muses, “Maybe someday, someone will find our names, among books or ashes, and know that we were here, that we mattered too.”

Being forced to flee home isn’t a new fear for Black people. Racially motivated violence by white supremacists in places like Forsyth County, Georgia, in 1912 forced Black people to find new places to call home. The 2017 white nationalist Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville brought this anxiety to Johnson’s doorstep. And, as a Black woman living near the epicenter of the clash that injured counter protesters and killed Heather Heyer, Johnson has carried those things to Thomas Jefferson’s former doorstep, a place where Black people worked to survive in the shadow of the country’s much revered third President.

Johnson’s historically tethered story collection is startlingly timely. In addition to systemic racism and hundreds of years of threats of violence and terror against Black people, other topics like the breakdown of the supply chain, infrastructure issues, power grid failures and environmental anxieties from storms and fires are made to feel close to the reader’s skin. Even though the title story was written before the COVID-19 pandemic, the feeling of the characters holed up in the house in “My Monticello” is similar to the tightness and panic many people felt being stuck in one place during the early months of 2020.

Johnson is a public-school teacher and many of the collection’s stories center around education and the ways that structure shapes who the characters are and who they might become. The collection opens with “Control Negro,” in which a college professor secretly grooms his son to be a model Black boy in a research experiment that compares his treatment by society and life path with the trajectory of an American Caucasian male.

“There are many studies now about the cost of race in this great nation. Most convincing is the work from other departments: sociology, cultural anthropology. Researchers send out identical resumes or home loan applications, half of which are headed with ‘ethnic-sounding’ names … They measure who gets the job, the loan… They mark which colored human-shaped targets get shot by the police, in study after study, no matter how innocuous the silhouetted objects they cradle. All these studies, I concede, are good, great work, but I wonder, is there something flawed in them that makes the findings too easy to dismiss?”

The teacher is willing to sacrifice his son to test his theory, but no one is prepared for what happens next.

All the stories are set in Virginia, where Johnson was born and lives, and they deal with the psychological and emotional costs of racism in haunting and unsettling ways. “Buying a House Ahead of the Apocalypse” is composed in the style of a checklist for a single mother. Items such as “Look for hardwood floors and hardwood trees, an arbor raising vines. Look for a patch of sun that might nourish a kitchen garden” are juxtaposed with “Vote, but don’t expect it to save you. March, but don’t expect it to save you. Pray, but don’t expect it to save you.”

The stories are a close study of the characters’ relationships to one another, the concept of home, the idea (real or imagined) of Virginia and all the hopes and promises America holds. Johnson is unafraid of experimentation, nimbly switching styles and perspectives. She constantly provides fresh, interesting characters, even in less agile stories like “Something Sweet On Our Tongues,” a series of vignettes that take course over a day at an elementary school. Johnson’s well-tuned poetic ear thrums throughout the text: “We hadn’t realized how hungry we were: We’d never once felt skin so prize beneath our own.”

A compilation of vivid, complex stories, at times reminiscent of works by Octavia Butler, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison and Colson Whitehead, “My Monticello” is a startling, beautiful debut collection of short stories worthy of its inclusion as a finalist for this year’s Kirkus Prize.

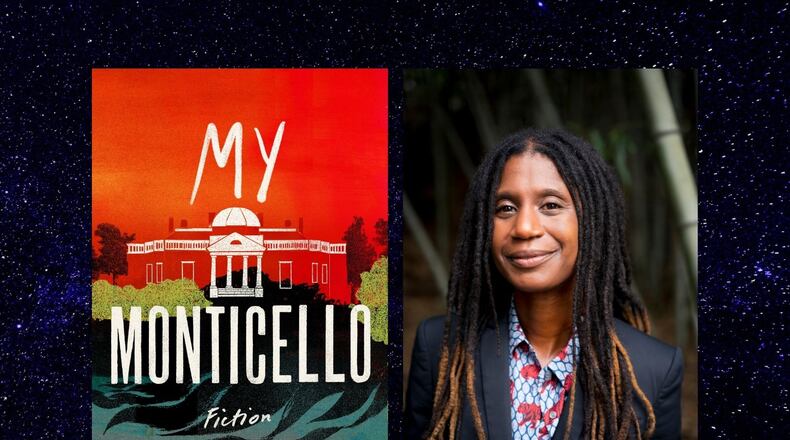

FICTION

By Jocelyn Nicole Johnson

Henry Holt & Company

210 pages, $26.99