Standing shoulder to shoulder with her lawyer, the defendant pleaded guilty in a Fulton County courtroom.

She agreed to testify against her onetime boss and others in a wide-ranging racketeering case, avoiding a lengthy trial and possible jail time. She apologized to the judge and the people of Atlanta and said she wanted to move on with her life.

The Donald Trump criminal trial? Nope. The Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal in 2014.

As Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis advances her criminal case against the former president and his top deputies, she is following a well-worn playbook, legal experts say, working her way up the hierarchy by leveraging Georgia’s sprawling anti-racketeering law.

The approach has created momentum in Willis’ investigation of Trump’s failed attempt to overturn Democrat Joe Biden’s victory in Georgia following the 2020 presidential election. Four of the case’s 19 defendants have pleaded guilty, including three lawyers who had prominent roles both in front of the cameras or behind the scenes in the Trump campaign. Each has agreed to be a cooperating witness as Willis zeroes in on Trump and his inner circle.

“Her case is getting stronger by the day,” said former DeKalb DA Gwen Keyes Fleming of Willis.

With the pace of guilty pleas accelerating, speculation now centers on which defendant will be next. Lawyers with knowledge of the case say prosecutors have floated plea offers to several other defendants, with some turning down offers of a misdemeanor and a sentence of probation.

Many outside observers argue that defendants have more incentive to agree to such deals now, especially if the DA’s new cooperating witnesses — Sidney Powell, Kenneth Chesebro, Jenna Ellis and Scott Hall — could implicate them.

“As they have their various motions decided, as they receive the discovery and as it becomes more clear that these co-defendants could start providing testimony against them, you’ll start to see others race to the DA to try to get the best deal possible,” said Fleming.

‘Bargaining chip’

Willis has successfully used Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act in other high-profile cases for years. Working with John Floyd, an Atlanta civil litigator widely considered to be Georgia’s leading authority on racketeering and conspiracy law, she has secured charges for a broad pool of defendants. This includes those in the APS test-cheating trial to the current Young Slime Life gang case, whittling down the field ahead of trial.

In the APS case, 35 educators were indicted but only 12 wound up at trial. Eleven of them were convicted. In YSL, 28 people were initially charged and eight have so far taken plea deals.

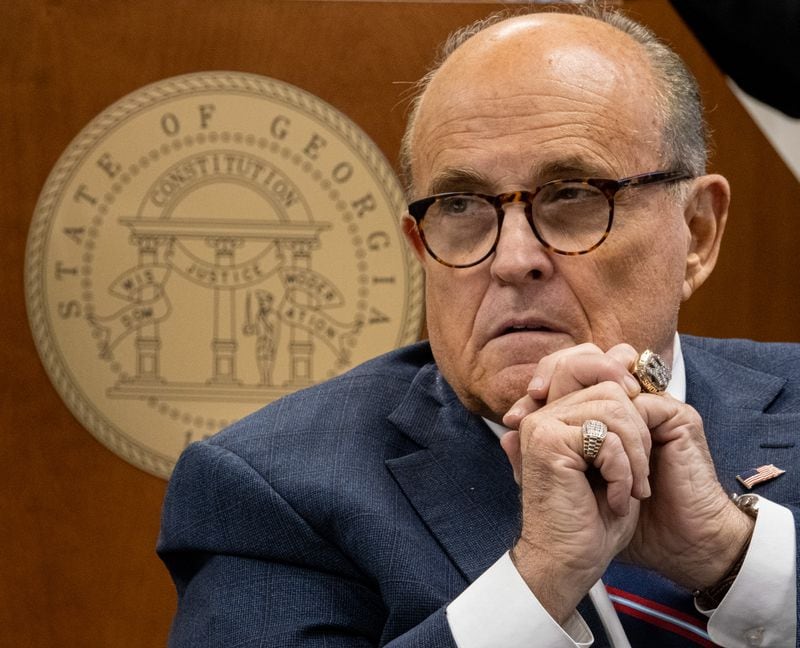

The 41-count indictment in the Trump case cites 161 actions allegedly taken by the former president and his colleagues, including former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani and White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, in what prosecutors call a “criminal enterprise.” The charging document also includes 30 unindicted co-conspirators.

“This is not only a classic organized crime conspiracy formula for success for a prosecution team, this is the classic format for a prosecution of any organization,” said Morgan Cloud, a law professor at Emory University. “If this were a white collar investigation of a corporation for alleged wrongdoing, it’s the same mechanism.”

The approach, however, has many critics.

“I think it’s overused and misused,” said defense attorney Bob Rubin.

Opponents argue that prosecutors use the threat of stiff sentences under Georgia’s RICO statute to intimidate defendants.

“It’s so broad that it can be used to put pressure of very strong penalties — 20 years in prison — on people who shouldn’t be facing anything close to that,” said Rubin, who represented Dana Evans, a principal who initially faced the prospect of more than two decades of prison time as part of the APS case.

Steve Sadow, Trump’s lead attorney in Fulton County, similarly called Willis’ RICO case “nothing more than a bargaining chip for DA Willis.”

APS strategy

In the APS cheating case, educators were accused of inflating the standardized test scores of thousands of students to make the district look better. Early plea deals Willis cut with some participants led to testimony that helped convict others involved in the cheating.

One of those who pleaded guilty was Millicent Few, the district’s human resources director. Originally charged with two felony counts, Few pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of malfeasance in office.

She agreed to testify against other defendants, including former Superintendent Beverly Hall. As part of her plea agreement, Few said Hall was aware of cheating and ordered her to destroy investigations of suspicious score increases on standardized tests.

Credit: KENT D. JOHNSON / AJC

Credit: KENT D. JOHNSON / AJC

Hall was charged with orchestrating the scheme. She pleaded not guilty but died of breast cancer before her case could go to trial.

Improving credibility

In the Trump case, Willis’s approach has yielded some early results.

Last month, Atlanta bail bondsman Scott Hall pleaded guilty to five misdemeanor counts for his role in a Coffee County election data breach. Last week, Powell pleaded guilty to six misdemeanor counts for her role in the same incident in south Georgia.

Two other attorneys, Chesebro and Ellis, subsequently pleaded guilty to felonies for their roles in the election interference case. Chesebro was an author of Trump’s alleged plan to use Republican electors to overturn the election in state legislatures and in Congress. Ellis made false claims of voting fraud as Trump’s campaign lobbied lawmakers in Georgia and elsewhere to overturn Biden’s victory.

Credit: Ben Gray

Credit: Ben Gray

Each of the defendants agreed to cooperate with prosecutors in upcoming proceedings as part of their plea agreements.

Fleming, the former DeKalb DA, said it’s notable that Willis now has deals in place with people involved in three of the subplots identified in the RICO indictment: Coffee County (Powell and Hall), Trump electors (Chesebro) and false statements about Georgia’s elections (Ellis).

“The law says you only need one witness to establish a fact. But having more than one demonstrates consistency, which always improves credibility, and could be more persuasive to a jury,” said Fleming.

Jeff Grell, a Minneapolis-based attorney and law professor who specializes in RICO, said he’s surprised that “pretty big players” like Powell and Chesebro have already struck deals.

“I would expect to see Fani Willis plead out a lot of the lower people a lot more quickly now that she’s getting some of the higher people,” Grell said. “If I were someone like Rudy Giuliani, I would be working night and day to get myself pled out. And if I were representing Trump, I think everybody who pleads out makes his case that much more difficult.”

For his part, Sadow has said he thinks the truthful testimony of people like Chesebro will help, not hurt, his defense strategy for Trump.

‘Nails them to the wall’

Critics of RICO say prosecutors use financial pressures to bring defendants who aren’t wealthy to the negotiating table to avoid hefty legal bills. Several defendants in the Trump case, including Eastman and Ellis, have taken to crowdfunding sites to help pay for their legal defense.

“Who has money to hire an attorney to be on a case for a year?” said Rachel Kaufman, a defense attorney unaffiliated with the Trump case. “It just nails them to the wall.”

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Rubin said that to represent Evans, the principal in the APS case, he personally “took a financial bath” because he knew his client couldn’t afford his usual sticker price. But many attorneys aren’t in the position to offer the same, he noted, since participating in a RICO trial typically requires turning away other clients.

Emory’s Cloud said such critiques of RICO have been common ever since Congress passed the federal anti-racketeering law in 1970 and Georgia enacted its own version a decade later.

“It is inherent in the structure of the RICO statute, which is crafted very aggressively and very broadly to reach root conduct,” he said, adding that the U.S. and Georgia supreme courts have consistently upheld the laws.

Looking ahead, most observers believe there will be more deals — perhaps with some big names. But they noted that the offers floated by prosecutors tend to get worse with time.

Willis’ plea deals historically are “more like fish than like wine,” said Norm Eisen, President Barack Obama’s onetime ethics czar who has closely tracked the Fulton case. “You want to make the first move.”

Staff writer Bill Rankin contributed to this article.