Finding family history a world away in Belgium

This story is told from the perspective of the reporter’s husband, offering a deeply personal account of his journey to find out more of his father’s history.

I could almost touch the Eiffel Tower from my window on the fifth floor of the Hotel de Sers in Paris. Steps from the Champs-Élysées and the Arc de Triomphe, this space situates me in a city moving in overdrive, a juxtaposition from the village of Dochamps, Belgium, I had just left.

My time here has been decades in the making, and with Paris providing reflection, I might not have found all the answers I wanted, but I made a tangible connection to my father for which I longed.

I’m easily distracted by Paris, in a very good way. Not surprisingly, its centuries-old architecture — from Notre Dame to the Louvre to the snakelike wrought-iron dressing Paris buildings — defines a city not willing to have its treasures destroyed during World War II. Here, history moves in every direction.

It’s formidable to think of the story’s ending had the French not surrendered. My eyes shift from the window to the desk and atop the hotel’s stationery, the letterhead reads, “We are stories.”

We are stories. And I am here to continue mine.

Unbeknownst at the time yet so defining, every moment becomes an integral part with each piece fitting snugly to complete life’s puzzle.

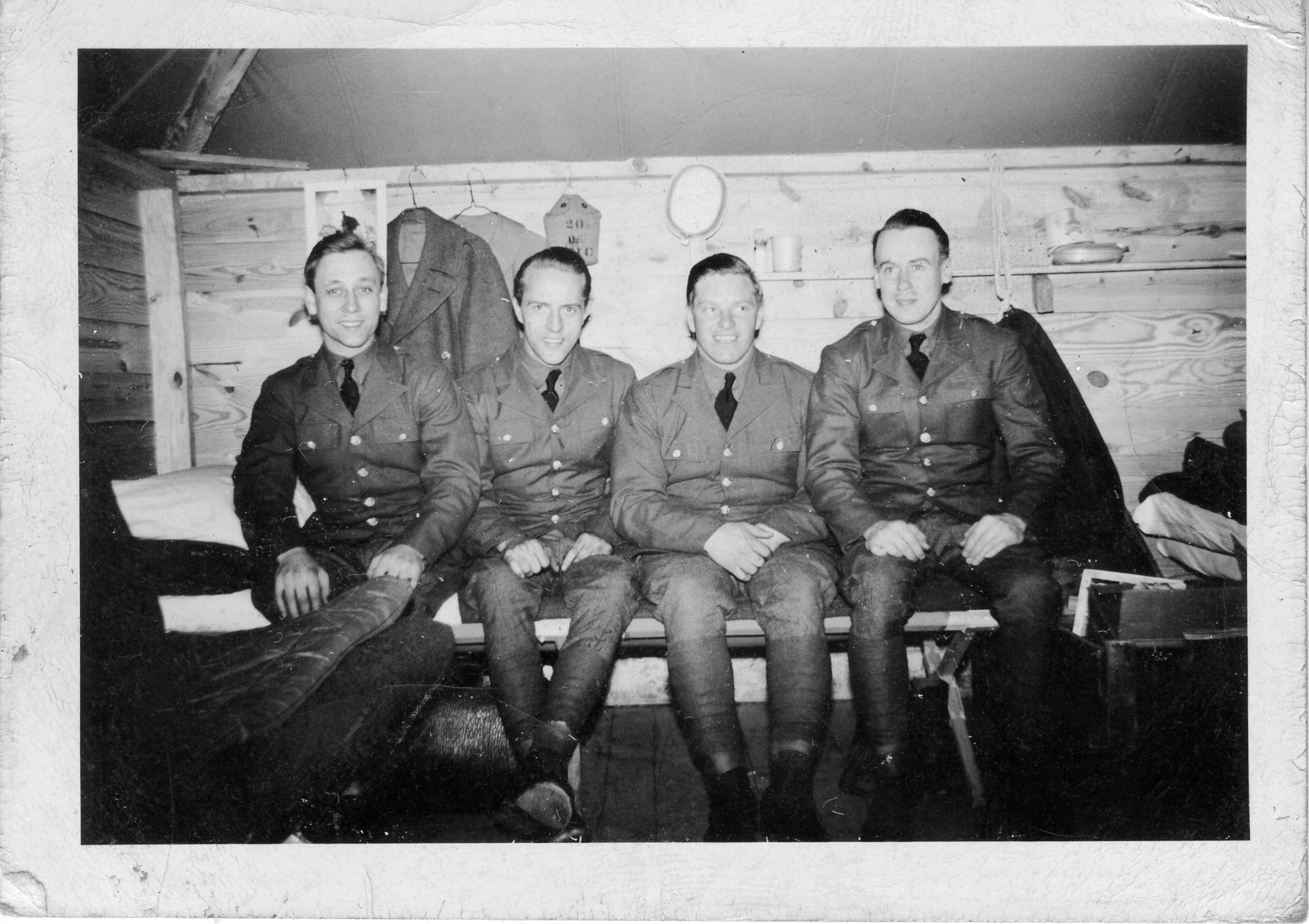

One story preoccupying me for over 50 years was my father’s military service. The details were a mystery because my father, Neil J. Garrison, never spoke of World War II, the brutal winter in Lamorménil, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge, or his Silver Star — the third-highest award in military service, given for valor in combat and gallantry in action — with his family or anyone else.

His enigmatic Silver Star

His commendation was my only reference.

“On 4 January 1945 … attacked the town of Lamorménil … troops entered the town at 1500 over snow-covered terrain and proceeded to clear it in house-to-house fighting … subjected to direct fire … S. Sgt Garrison and two other men assaulted the house … 24 enlisted men were forced to surrender … the building was a [enemy]communication center. After destroying the equipment, [he] and his squad continued to fight through the town until it was secured that evening. [His] courage, aggressiveness, and coolness under fire were an inspiration to his comrades and a credit to himself.”

It wasn’t until decades later that my father held his medal in his hands, after friends and family convinced him to apply and receive the actual medal. He didn’t want it; in fact, he never took it out of the box. He believed that it belonged to his entire squad, not simply him.

I needed that connection to him now, and I wanted to know more. With the citation as my guide, I focused on Lamorménil.

Go where the bad guys were

Most soldiers found themselves where the bad guys were. Through North Africa, Sicily, France then Belgium, my dad’s liberating assignments weren’t metropolises, but small villages, crossing open fields, taking machine-gun fire, meeting his objective, day after day.

The Ardennes region — parts of Belgium, France and Luxembourg — is mountainous, smothered in towering pine trees, much the same as in 1945. Small hamlets like La Roche, Dochamps, Bastogne and Lamorménil, all of which had been liberated before, became the site of intense fighting during the winter of 1945. These villages held no prize like Paris, but they stood in the way of Hitler’s objective: the port of Antwerp. Enter the Allied Forces, multiple disciplines, including the 2nd Armored Division, ‘Hell on Wheels’, my dad.

With local author and historian Eddy Monfort as guide and translator, we drove into the heart of Lamorménil — equivalent to a Southern one stoplight town, if that — entering from the northwest, the same as my father entered on foot. The stone church’s bell tower, confirmed to have been hit during the invasion, remains standing defiantly at the crossroads.

The only sign of life in the village was two older men leaning against a house enjoying the shade. Monfort took the opportunity to ask questions. Speaking in an old dialect of French, the two welcomed us.

When Monfort explained our presence, and before answering, each offered, “Thank you.” Every time, without exception, once my purpose in Belgium became known, a word of gratitude for my father’s service followed. One remembered being a young child and his parents gathering everyone and running for the woods. Day after day, they hid within the trees, sneaking back at night to feed livestock, then fleeing back to their hiding place.

Over 80% of Lamorménil was destroyed. Walking down the road where a handful of homes stood, Monford explained that many were built postwar on existing foundations, displaying remnants of shrapnel dug deep in corners and frames. Most evacuated Lamorménil when the Germans arrived, but some, like Monfort’s grandparents in Dochamps, remained.

Walking the Lamorménil road

My brother Arthur is quick to state that our father didn’t think of himself as a hero.

“He remembers other guys who were doing heroic things, were maimed and some gave everything they had. These men were just trying to win the war as soon as they could, so they could go home,” he said.

But then again, Arthur said with a laugh, they didn’t hand out Silver Stars like Skittles.

My father did do something heroic and, although I will never know the entire story of that winter, other than his entry into Lamorménil, he did what he was ordered to do.

The soldiers of that generation never hesitated in the fight. They knew the effort was much bigger than this one village at the end of the road, and every move made contributed to shortening the war and saving lives.

Walking that road, although simple and relatively insignificant to the story I sought, I felt him with me. His rugged, calloused hands signaled the way. The only difference, in my mind, was the Silver Star was there, pinned strategically on his uniform’s left chest pocket, completing his extraordinary story of service.