Remembering soccer’s Chiefs, 50 years after they won it all

It was a busy late-September Saturday in 1968, the day Atlanta won its first professional championship.

Both Georgia Tech and Georgia had home dates in football, Bud Carson’s boys tangling with a ranked Miami down the road at The Flats. And the Braves were putting the bow on their third season in town – a break-even, 81-win campaign – with a matinee at what was then called simply Atlanta Stadium. They lost to the Dodgers and some pitcher named Don Sutton that day, in front of an intimate gathering of 6,095.

“If the Braves had gone into extra innings, we would have been in big trouble,” remembered Bob Hope, whose baseball job came with the bonus of hyping up a subsidiary of the Braves, the Atlanta Chiefs of the first-year North American Soccer League.

He had come to that task eminently unprepared. “I thought s-o-c-c-e-r spelled saucer,” Hope said with a chuckle. “I had no idea what soccer was, which was pretty typical for Atlanta at the time.”

Quickly, the home of the Braves and the American Pastime was transformed into a soccer pitch. The mound was shaved. The stands were cleared. A crowd a fraction of what their heirs, Atlanta United, would draw a half century later took up the Chiefs cause as they played the San Diego Toros for the NASL title. Still, a better draw at least than the Braves that day, nearly 15,000 watched the Chiefs win 3-nil.

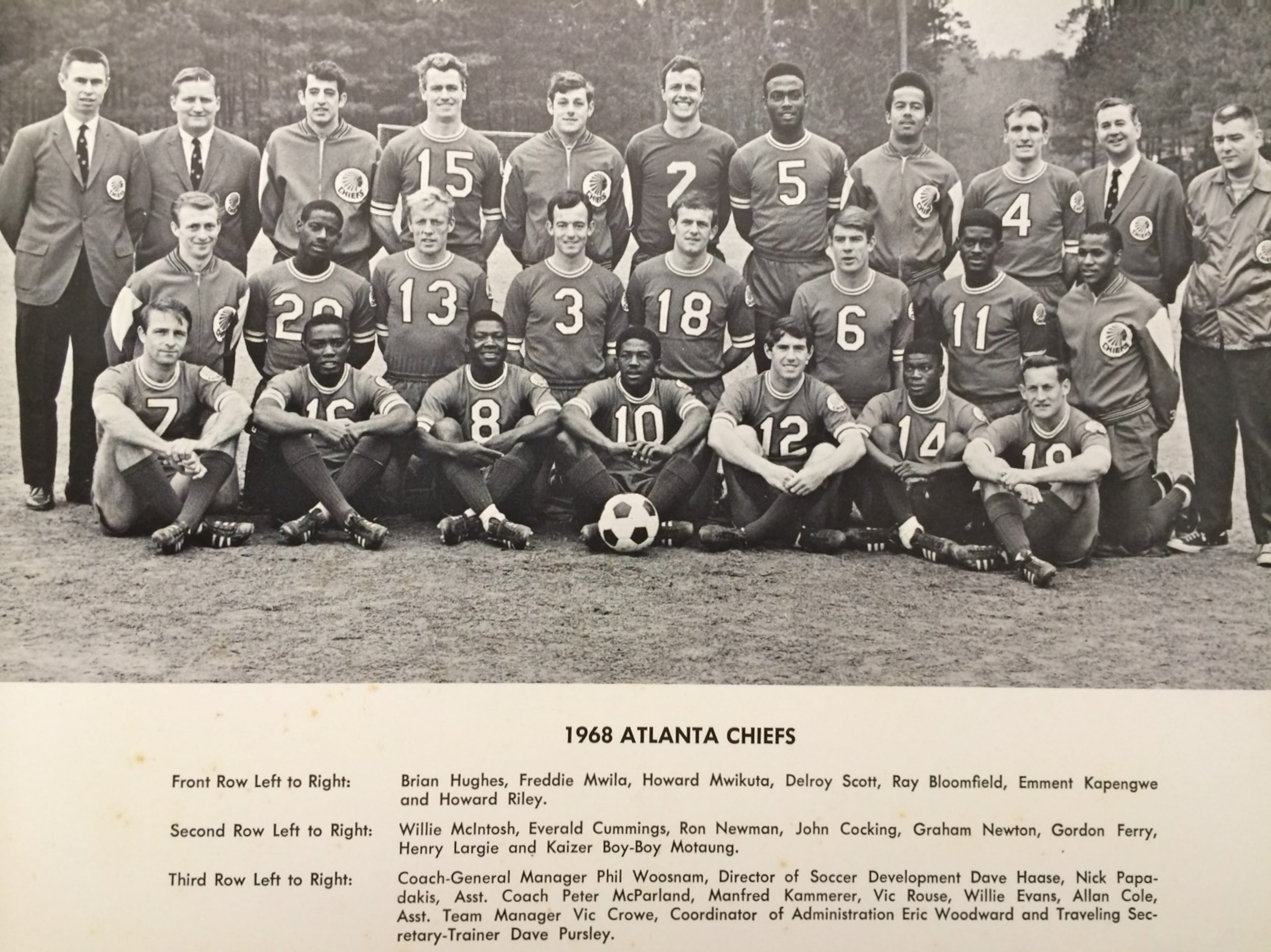

Those Chiefs introduced an emerging Atlanta to the world’s game. And this championship broke all the bounds of provincialism. Scoring those three goals and showing the way to the kind of victory still so elusive to a city fully grown were a Northern Irishman (Peter McParland, a decade removed from World Cup stardom back home), a Jamaican (Delroy Scott) and a South African (Kaizer “Boy-Boy” Motaung, the Chiefs star and league’s rookie of the year that season).

Here it is, the 50th anniversary of a championship that is seldom remembered for a team that existed but 10 seasons in two different incarnations (1967-73 and 1979-81). Yet, in light of the civic stir created by Atlanta United as it begins its second MLS season, how can you not reach back to these beginnings and appreciate the Chiefs as a spark that lit a very slow-burning fire?

Dick Cecil, the former Braves executive and Chiefs VP who was charged with keeping the stadium filled with all kinds of amusements, including soccer, gets downright insistent on the topic of the Chiefs place in Atlanta’s sporting history.

“This is the first professional championship in Atlanta. I’ve been to things that they just talk about the (Braves 1995) World Series. Well, excuse me. I always want to underscore that (the Chiefs) paid their dues, they did a hell of a job and they are really responsible for Atlanta’s soccer scene. They were the base. And Atlanta United exploded on top of that,” he said.

It is worth noting that the Braves owned the Chiefs, so, in essence rather than argue which team produced the first “real” championship, it can be said that one franchise can just go ahead and claim both.

“(The Chiefs) opened the door. Every journey has to begin with a first step,” added Elliott Levitas, a state representative of that era who was among those drawn to the foreign concept of soccer as practiced by the Chiefs.

To look back on that time is to recognize how much foundational concrete had to be poured before a phenomenon like Atlanta United could stand.

Born in 1967 as a member of the renegade National Professional Soccer League, the Chiefs were folded into the new NASL a year later.

Soccer was a counter-culture game for a counter-culture time. And it proved to be another avenue for an ambitious city, one that was just adding pro baseball, football and basketball, to show how cosmopolitan it could be. Those doubting a southern city’s ability to pay the slightest attention to soccer included many in the NASL itself.

“People in the league said we were crazy,” Cecil said. “But it was the right time to introduce soccer.”

From Cecil’s perspective, he had never witnessed a soccer match before signing on to add the game to the stadium’s menu of events. He had, though, read accounts of the thrilling 1966 World Cup, won in extra time by host England. And eventually became enchanted by the personalities involved while traveling the world with Chiefs player-manager Phil Woosnam to stock the new team with players.

Like any good missionary, the Chiefs invested heavily in proselytizing. Spreading the new word of soccer was a large part of the players’ responsibilities, and they were thrown to a curious, if sometimes skeptical, community.

“There was a great deal of interest if, for nothing else, you were an Englishman and you were different,” said then-midfielder John Cocking, one of the few former Chiefs who settled in Atlanta – veering into banking after his playing days.

“I used to tell them, ‘Soccer is played in more countries in the world than those where Coca-Cola is sold.’ And even that often times had little to no effect,” he said.

And, like any good propagandist, the Chiefs realized they had to sell their ideas to the children. Arriving at a landscape nearly devoid of youth soccer, the team went to work developing programs from scratch. According to a 1968 report by the Chiefs, there were fewer than 150 souls playing organized soccer the year they arrived.

And, by mid-1968, the report stated, “nearly 16,000 Atlantans are playing soccer on amateur teams in the area.

“Where there were only six high schools fielding varsity teams in 1966, 42 teams with more than 2,000 players competed for the Georgia High School Associate state championship last winter.” The team purported to have held 390 clinics around the state.

The 1968 season-ending NASL report lauded Atlanta: “Where soccer was virtually unheard of and unknown before 1967, the interest among youngsters has been one of the amazing stories of the year. Thousands of new fans have been created virtually overnight.”

Atlanta United drew 67,000 to its one home playoff game last season. It set a MLS season and single-game attendance records. In advance of Sunday’s home opener, season ticket sales for Year 2 were approaching 40,000. Two generations after the Chiefs began sowing seeds, that is the harvest.

The ’68 Chiefs in particular were the model for how to sell pro soccer to the hesitant American consumer of that era. They were winning, and that, as United proved, is always vital in this market. In Woosnam – whose off-field gifts were such that he eventually rose to rank of commissioner in the NASL – the Chiefs had an able and willing pitchman.

The wacky promotional gimmick was always in play, like the time in advance of an international exhibition game against Coventry, the team commissioned an attractive young woman to ride horseback down Peachtree Street. The intent was to recreate, in a slightly more modest way, the ride through the streets of Coventry of another famed equestrian, Lady Godiva.

And, by the time Santos of Brazil, and a 28-year-old Pele arrived in Atlanta for another exhibition, the Chiefs had built him up so that “these people who a month before had never really heard of Pele mobbed him at the end of the game,” Hope remembered.

In what many considered a larger accomplishment than winning the first NASL title, the Chiefs not once, but twice, beat English First Division champion Manchester City in exhibition matches. It didn’t hurt that Man City was winding down from its season and that the canny Woosnam made sure to wine and dine and entertain his guests in the midday southern sun as much as possible before the game. But the wins still resonated even across the pond, and long before the arrival of the Summer Olympics, Atlanta enjoyed a smidge of international cachet.

“I like to say back in 1967-68 there were five things Atlanta was known for internationally: Coca-Cola, Dr. (Martin Luther) King (Jr.), Lockheed, ‘Gone with the Wind,’ and the Atlanta Chiefs,” Cecil said.

Atlanta still owes its first champion a victory parade. The Chiefs, through Levitas, got a nice proclamation from the Georgia Legislature, but little other fuss was made. Cocking remembers receiving a championship ring, but somewhere through the years he lost it.

While the NASL enjoyed some serious ownership – like Lamar Hunt in Dallas and William Clay Ford in Detroit and Jack Kent Cooke in Los Angeles – it expired as America’s premier pro league in 1984, outliving the Chiefs by four years. While stimulating a certain amount of interest in soccer, the Chiefs could not transform that into a profit.

They would not fade, however, before commanding a page in the skinny pamphlet that is the history of Atlanta professional championships.

Fifty years is ancient history in a world of manic change and flighty tastes. Atlanta United very much owns the moment. Who has time to think about the Chiefs much anymore? There’s chanting and drinking and a bit of reclamation to be done after United’s blowout loss to the Houston Dynamo on Saturday.

But, that’s OK.

“I see us very much as pioneers,” Cocking said. “I do take pride in that, yes, I do.

“I don’t bother reminding people about (winning a title). I’m very proud of it, it’s part of my life, but it doesn’t have to be part of anyone else’s life. I don’t have to try to sell it to people. I’m happy with what I accomplished here and the life I’ve lived here.

“I don’t have to say, ‘Remember 1968, when the Chiefs won the championship?’”