“As If We Were Ghosts,” a documentary about African American athletes, coaches and teams of the old Georgia Interscholastic Association, shines a new light on how their athletic and social exploits have impacted the state for more than 50 years.

The one-hour special, which will premiere Monday night at 9 on Georgia Public Broadcasting with a second showing on Juneteenth Sunday at 5 p.m., will have interviews with NBA great Walt Frazier and Olympic gold medalists Wyomia Tyus and Edith McGuire, all former standouts in the GIA, which administered sports for Georgia’s all-Black high schools from 1948 through 1970.

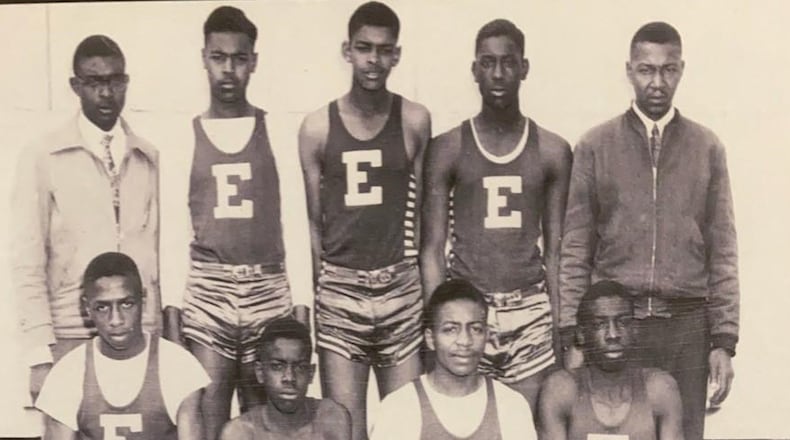

The documentary also will spotlight lesser-known athletes who never got media coverage in their day, such as 91-year-old Charles Freeman, a member of Eatonton Colored School’s basketball team from 1950.

The documentary is nearly two decades in the making. Former GPB executive Herb White, the former Decatur High, Georgia and Atlanta Hawks basketball player, initiated the project in 2004, but GPB shelved it in 2011, when White retired.

Then last year, Atlanta real estate developer Ron Bivins, a former outstanding GIA athlete, was inspired to fund its completion himself. Independent filmmaker Monty Ross, working with DeKalb County-based Our Studios, is the director, brought on in March. Fox Sports sportscaster Pam Oliver, who began her broadcasting career in Albany, serves as a voice actor.

Co-producer Bivins said his passion for the project is personal. He was a three-sport athlete and starting quarterback at A.L. Staley High, which now might be called a ghost school. The all-Black school became a junior high in 1970, when Americus High integrated, merging student bodies. The original Staley school building burned down suspiciously, according to Bivins, in 1972. Its sports history seemed to die with it.

Bivins was Staley’s quarterback. His counterpart at the crosstown white school, Americus High, was Chan Gailey, who would make the AJC’s All-State team and gain more fame as a coach with the Dallas Cowboys and Georgia Tech.

The media infrequently named or recognized GIA all-state teams, but the GIA had newsworthy athletes just the same. Bivins recalls a basketball teammate, Paul Jones, who scored nearly 70 points in a game and a track sprinter, Frank Seay, whom he says was faster than Americus High great Mackel Harris, an African American football star who came along a few years later and gained notoriety statewide at the previously all-white Americus school.

Harris and Americus High teammate Kent Hill went on to star at Georgia Tech, and Hill would be the first Black player from Americus in the NFL, but Bivins’ contemporaries went unrecruited by the top historically white college programs and were unknown outside their local Black communities and virtually ignored by the media. Yet Bivins said they were looked up to by young Black kids such as Harris and Hill and made a difference in their towns.

“We had great athletes that could have played for anybody, but they didn’t have the weight room and the training,” Bivins said. “We didn’t even have a track team. When they went to Americus [after integration], they had everything. We had nothing but natural talent.”

White, now living in Mexico, is thrilled that Bivins has championed the project. When White was playing at Decatur in the mid-1960s, The Atlanta Journal published weekly rankings of the best basketball players in the state but ignored GIA stars such as Frazier, who graduated from Atlanta’s Howard High in 1963. In White’s senior year of ‘65, White was ranked No. 1 with no African American players listed.

“I had been playing in the summer with guys from all-Black gyms around Atlanta for three years,” White said. “I knew there were guys with talent equal to mine who were never mentioned. I felt somewhat embarrassed.”

Among them were Garfield Heard of Hogansville and Don Adams of South Fulton. Both would play many years in the NBA.

But “As If We Were Ghosts” isn’t simply about recognizing GIA athletes who went on to fame, and there are many, including the NFL’s Emerson Boozer and MLB’s Donn Clendenon, along with Tyus and McGuire, the Georgia best friends who finished 1-2 in the 1964 Olympic women’s 100 meters.

Ross, known for his film projects with fellow Clark Atlanta classmate Spike Lee, was moved by the story of Freeman, a surviving player from an Eatonton GIA team that won a basketball championship who still remembered plays his team ran 72 years ago. Ross also enjoyed the story of Houston High’s 1969 championship team, which got no recognition outside the GIA in its day. The city of Perry honored the team with championship rings in 2020.

“The thing that stood out to me was the resilience of the athletes and former students,” Ross said. “They were holding out for the day they could have a piece of their history that has languished in their brains for so long so they could finally show their relatives, their grandkids, that all the stories they’ve been talking about for 20-30 years were true.”

Bivins said he hopes the documentary brings to light the accomplishments of forgotten stars but also serves to give modern African American athletes a better perspective of history.

“I look at the money these kids are making today. They need to know whose shoulders they’re riding on, the people who came along before them to help pave the way,” Bivins said. “They are the benefactors of what was done in the ‘40s through the ‘70s. And I tell them to give back. Reach out and pull some others up just as some of them pulled you up but never were recognized.”

About the Author