The cantankerous journalist Bill Shipp once surprised former Gov. Roy Barnes with a prediction that they’d both have good crowds at their funerals. Barnes, taken aback, noted that both weren’t exactly universally beloved.

“No,” Shipp told the Democratic governor. “They would want to make sure both of us were dead.”

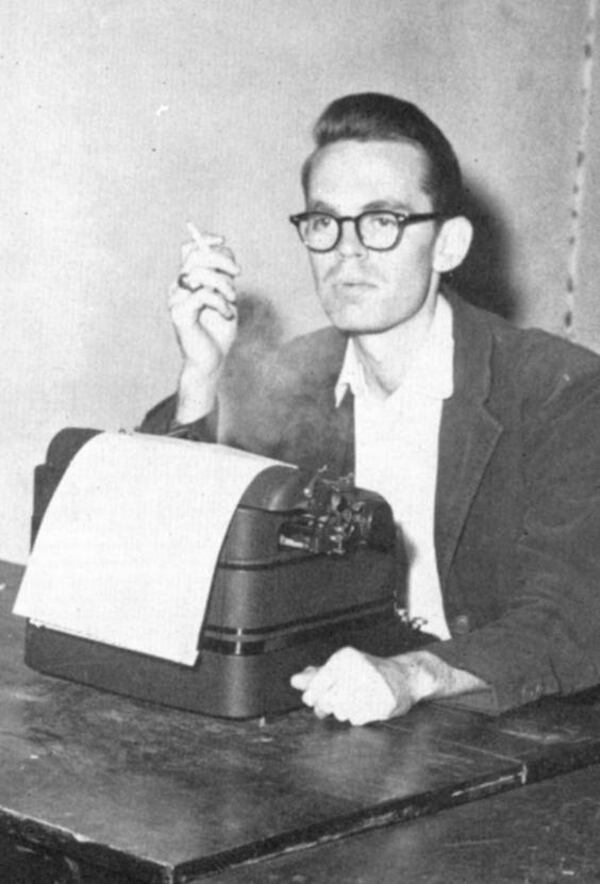

Shipp, who died this month at the age of 89, was laid to rest on Friday in a ceremony that honored his legacy as a pugnacious journalist who terrorized a generation of Georgia politicians — but also earned their enduring respect.

His friends and family members shared stories of the enterprising newsman, a Cobb County native who over more than 50 years chronicled the civil rights movement, Jimmy Carter’s rise to the White House and the state’s Republican revolution.

“He could tell you everything about everyone — good and bad,” said Barnes, who called him the state’s version of a political “Google” of the pre-Internet age.

Shipp made his mark in journalism early, as a 20-year-old managing editor at The Red & Black, the University of Georgia’s daily student newspaper, when he encouraged the segregated law school to admit Horace Ward, a Black applicant.

“What a miserable system it is when a university allows students of every race, creed and color — except black — to roam its campus and mix with us Anglo-Saxon Protestants while the southern Negro, a born U.S. citizen, is placed in a segregated group as if he were a leper,” Shipp wrote in an October 1953 column that was read aloud at the funeral by former U.S. Rep. Buddy Darden.

Credit: File.

Credit: File.

That column helped trigger his ouster from the newspaper, which was then run by the university, and hastened his departure from UGA. He joined the U.S. Army. When he returned to Georgia in 1956, he was hired by The Atlanta Constitution, where he eventually landed the premier political beat.

He threw himself into his job, developing a deep network of sources as he covered every aspect of state politics. Among his scoops was first word in 1974 that Carter, then the governor, would run for president two years later.

But Barnes also remembers how Shipp landed the news in 1971 that Carter appointed David Gambrell to a U.S. Senate seat: Apparently, Barnes said, Shipp hid in the bushes outside the Governor’s Mansion and tracked Gambrell’s arrival.

No one was spared from a torching by Shipp. Even Shipp’s pastor, the Rev. Hal Cole, noted an inscription that Shipp wrote before his death. It was addressed to the “best minister I’ve heard … lately.” But Shipp’s irascible approach and take-no-prisoners attitude earned him the begrudging admiration of the state’s most powerful politicians and power brokers.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

“He was the bane of every modern governor that has existed in the last 50 years,” Barnes said. “But you know something? We read every word he wrote.”

His family shared another side of Shipp’s story. Stephen Vreeland, who is married to Shipp’s granddaughter Hillary, spoke lovingly of conversations about the latest headlines and mundane, everyday occurrences with “Papa Shipp.”

He had an uncanny ability to not just tell stories but also make his family and friends feel like they were heard, Vreeland said. He also never lost his passion for journalism.

“I need to start writing again,” Vreeland recalled Shipp saying during particularly newsy political stretches. “This is getting ridiculous.”

Barnes, who served as governor from 1999 to 2003, shook his head as he recalled the scandals Shipp foiled and poorly drawn ideas he eviscerated in his must-read columns.

“If it were not for Bill Shipp, the things that would have been done in that Capitol by the politicians to the detriment of the people in this state,” Barnes said. “He kept them straight. And we owe him a debt of gratitude.”

About the Author