Opinion: Mental health an issue in justice system

I’ve written before that crime is a social disease. In my legal experience, the criminal mind tends to justify its bad behavior by shifting blame. Somebody else lied about or hurt me, somebody else has more than I do – so I reacted. Not my fault. Sometimes it all just seems so unfair that people actually believe their own lies – maybe you’d call that an empty conscience.

Then there are those with mental health issues, the disorganized mind. Insanity at the time of the offense is a jury question – could the defendant determine right from wrong? That defense is rare and difficult to assert. In daily practice, a much more common problem is incompetence – whether a defendant can assist the attorney with trial preparation.

Here’s where it gets thorny. I can recall a handful of clients truly incoherent at our first meeting, with many of those in drug withdrawal. It takes time to develop an impression of someone, and we are not a patient society. I shall not forget the young woman arrested for breaking into a stranger’s Mercedes to sleep on a freezing night – a heartbroken delusional mother who’d lost her child and begun drifting across the country. How did she get to Atlanta? Her haunted, broken mind made me wonder about life’s fragile journey. After a couple of cycles through court, she was directed to the county health authority and I never saw her again.

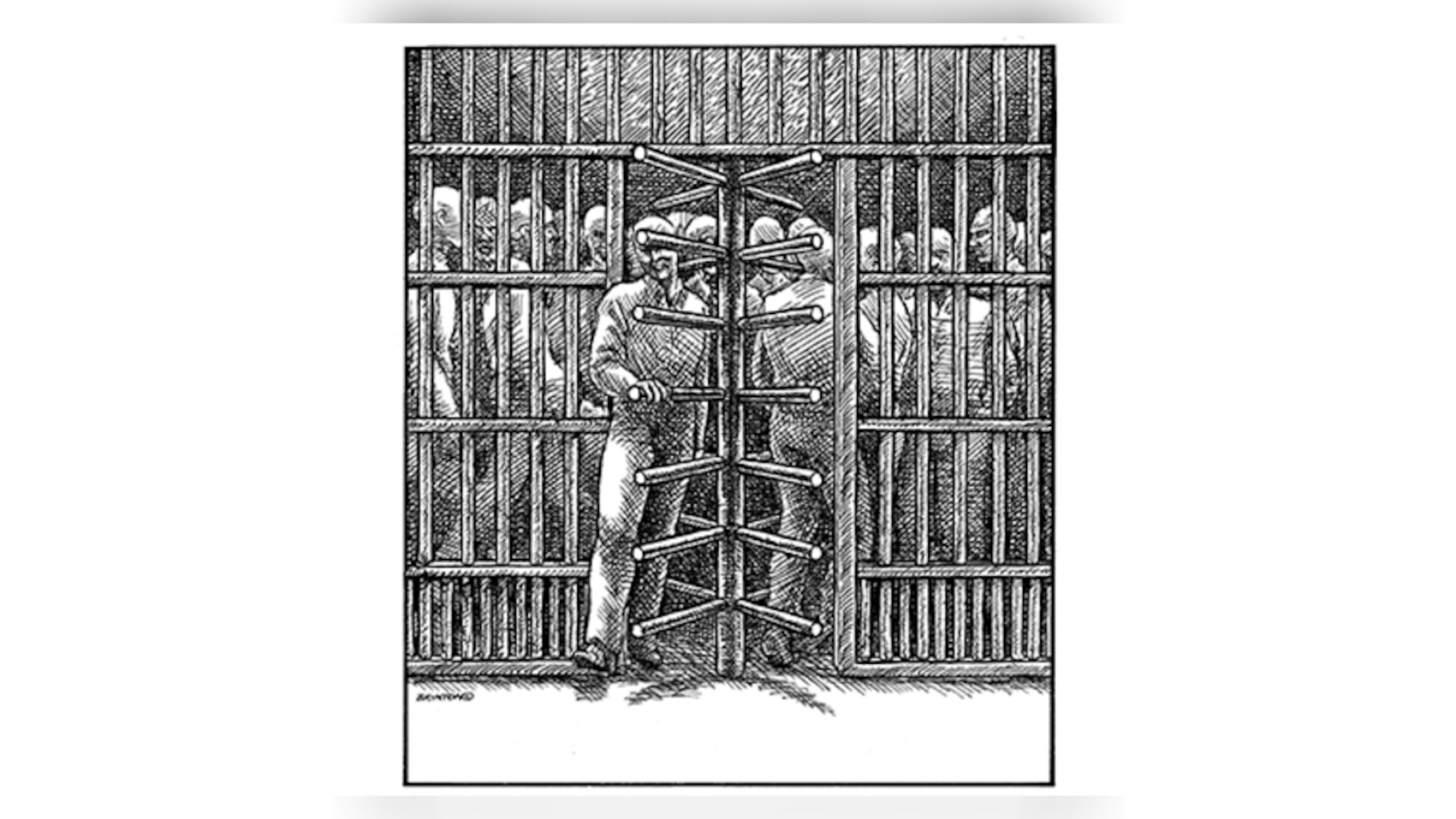

Most situations are more complicated than hers – especially when there’s a terrified or injured victim, or when dangerous drugs are involved. The problem is that our jails are de facto psych wards, detox centers and temporary housing for so many troubled people. In a society of fragmented communities and free agents, incarceration swells with outliers. Local jails are blamed for suicides and drug deaths – mental unwellness kills – but we recognize that the mentally unwell can also kill. Judges hesitate to release unstable people, and for good reason. I’m not talking about the lunkheads who won’t take a good deal.

Earlier this year, I represented a young man diagnosed with schizophrenia, arrested for marijuana distribution and fleeing. On bond, he missed a court date while institutionalized and then threatened his bondsman and previous lawyer in a manic state, resulting in new charges. It alarmed a lot of people in the county, understandably so. In jail, I encountered a religious, paranoid fellow – he understood he’d fallen below a standard, but he believed the court would reject our plea deal, and he was preoccupied with unimportant details. Law is hardly an exact science, and I had to tiptoe around the psych issues before the judge, while facilitating an outcome I knew to be in my client’s best interest.

That client really needed to stay on his medication, and I told his exasperated mother as much. She was well aware but busy working and unable to force compliance in any case – a common refrain in my practice. I often feel bad for families in this situation, because they feel responsible for a loved one’s condition beyond their control.

Still, we must be realistic – there is a strong correlation between mental health and criminality. Unwell people do not always take actions to improve themselves, preferring instead isolation and intoxication. Apathy harbors hatred, and people are hard to reach. These days, especially with COVID restrictions, it is taking months for psychological evaluations to be completed by the state, making that option less attractive to low-level inmates in lockup.

Mental health issues do not dominate the numbers of misguided and plain mean people in the justice system, but they certainly muddy things up. Viewed from a certain angle, this problem reflects a purer tragedy, laying bare the impersonal nature of our times. The asylums of old were cruel and confining, but they were stabilizing. Now, the unwell, pushed out by struggling town and family, end up in the general population. Sheriff’s deputies, overwhelmingly good men and women, are not equipped to identify and treat such people – it’s just asking too much.

We must take the world as we find it. Kudos to Sheriff Craig D. Owens Sr. of Cobb County for adding a psychiatrist to the jail. Not long ago, I had a client commit suicide there – to me, at least, the man gave no indication of depression, although he did have a serious charge in another state. Among the hysterics and politics, having a trained professional available is not going to hurt – we must acknowledge a problem to address it, and the stigma of mental health remains.

Douglas D. Ford is a commercial litigation and criminal defense attorney in metro Atlanta.