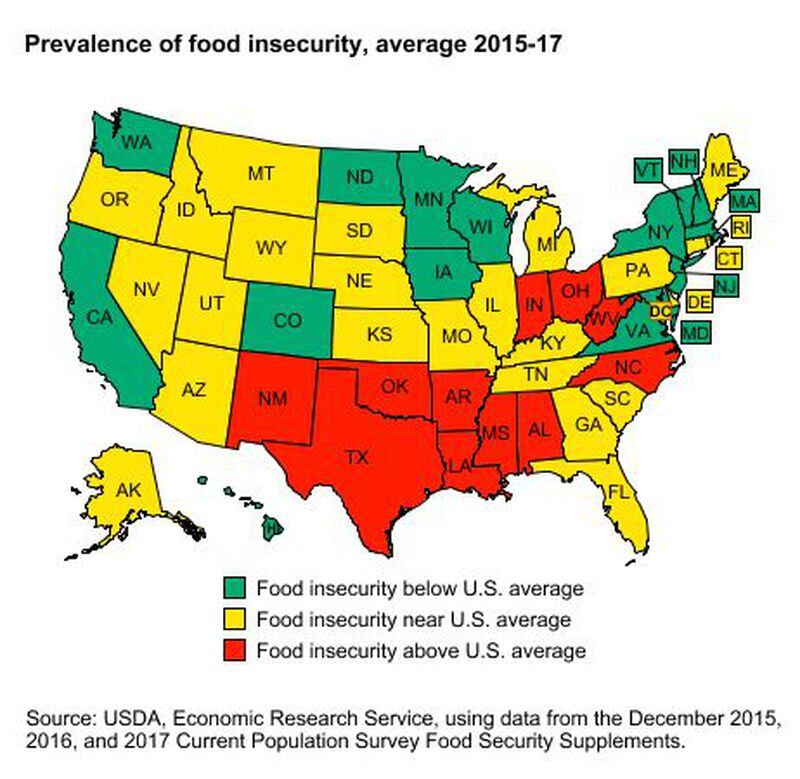

If you look at a map of Gwinnett County School Board districts, you might be surprised that each one has pockets where at least 10 percent of the residents often have to choose between rent, keeping the lights on, gas for the car or food for the children. They have what advocacy groups call “food insecurity.”

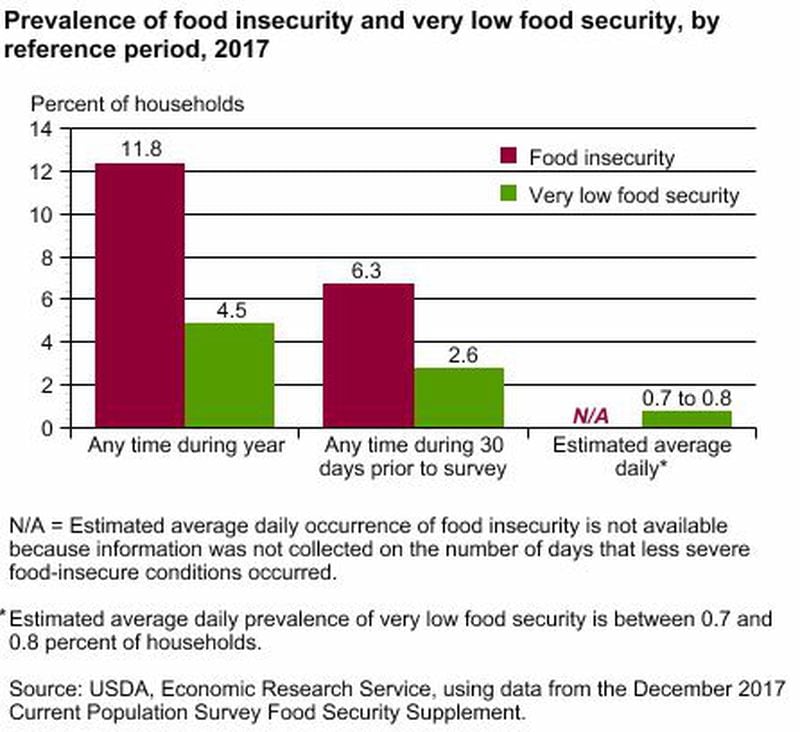

The term defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture is the lack of consistent access to adequate food resulting from the lack of money and other resources during the year. And it doesn’t just affect people who are below the poverty level, according to data from the Atlanta Community Food Bank.

Poverty is just one factor that can make it difficult for families to make ends meet. With the federal poverty level at an annual income of $24,250 for a family of four, people who make far more than that often find themselves going without.

Graves Elementary School is an area where a few miles in either direction shows income levels across the spectrum. With 93 percent of the students receiving free or reduced lunch, making sure they actually get to eat became a goal. With 1,200 students arriving in the morning at virtually the same time, there was often a bottle neck in the breakfast line.

The Atlanta Community Food Bank awarded the school $6,000 of a $30,000 grant for Gwinnett County Schools. Graves used its portion for food carts in different parts of the cafeteria that allowed several access points so everyone could have something in their bellies to start the day.

“The success of that program was encouraging,” said Michele Chivore, director of the Children’s Nutrition Program at Atlanta Community Food Bank. “We saw 15 percent more students eating breakfast.”

Principal Clayborn Knight worried that many of his students were not eating again after they left school. He met with Food Bank officials in October and in January Graves became the first school in Gwinnett County to launch the Atlanta Community Food Bank Food Pantry/Market Day Program. It allows parents to "shop" for both perishable and non-perishable items that serve five to seven meals per household. For most shoppers it amounts to 40 to 50 pounds of food with about a quarter of it being fresh produce.

The next market day is set for 3:30 to 5:30 p.m. Feb. 19. Subsequent Market Day events will be held the third Thursday of each month.

“We expected about 60 families and about 70 showed up,” Knight said of the first Market Day. “We even had people coming in after it was over. We’re going to shoot for about 75 next time.”

The program, launched in 2017, has seen success in other school districts. Graves became the 40th participant. Most are in Atlanta Public Schools, but Clayton, Cobb, DeKalb, Floyd and Fulton counties have schools involved.

“Unlike programs where students take home a backpack of food on Fridays, we wanted to connect kids to resources through their parents,” said Chivore.

Eventually, Chivore said, they'd like to see these pantries self-sustained by the schools. Besides the individual schools, the district nutrition program has a hand in making it work.

An educator for 25 years, Knight said he’s excited that this partnership provides another resource for helping educate the “whole child.”

“You can’t focus on a test or a lesson if your stomach is rumbling,” he said.

“This was a lot easier than I thought it would be,” said Knight, adding that there are specific guidelines and recipients have to fill out paperwork. But for four hours a month, his school gets to extend its community reach and take a burden off families.

“This goes hand in hand with what we do already,” he said. The school doesn’t roll up the doormat at 4 p.m. There are often movie nights, school dances, homework help and other ways to keep students, parents and community members engaged with the institution.

“This program is certainly a gift that keeps giving,” said Knight.

About the Author