Award-winning, North Carolina-based writer Randall Kenan died in 2020 at age 57, shortly after the release of his short story collection, “If I Had Two Wings.” He was renowned for his fiction and his groundbreaking portrayals of gay, poor, Black Southern characters in the novel “A Visitation of Spirits” and short story collection “Let the Dead Bury Their Dead.”

Kenan also crafted several significant works of nonfiction, including “The Fire This Time,” inspired by the James Baldwin book of a similar name.

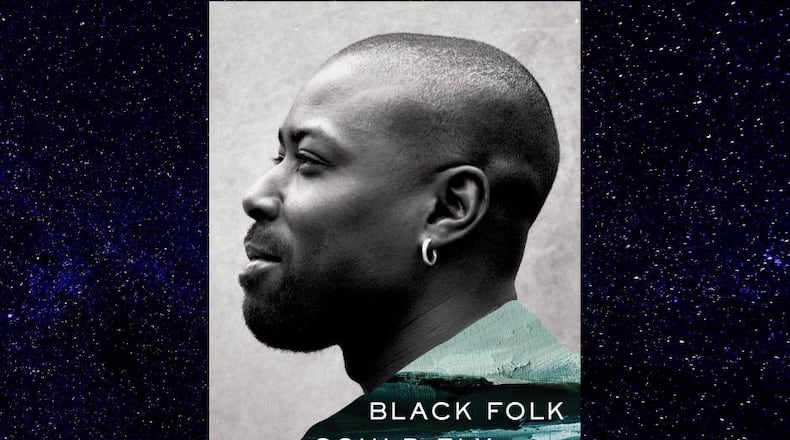

This new book, “Black Folk Could Fly: Selected Writings,” is a posthumously released collection of 22 nonfiction pieces that explore the author’s boyhood, the culture that raised him and the philosophies that honed his intellectual efforts.

By his own accounts a voracious reader and eater, it is no surprise that his pieces on Southern foodways sparkle with personality and color. “The hull is acidic and the pulp, when ripe, sweet like candy. Mr. Proust had his cookies; I have my grapes,” Kenan declares in “Scuppernongs and Beef Fat: Some Things About the Women Who Raised Me.”

Kenan was born in Brooklyn but was bought to his father’s people in Duplin County, North Carolina, at 6 weeks old. He spent his adolescence ensconced among tobacco fields, hog pens and acre-sized gardens, and his acute attention to sense of place permeates his work, no matter the genre.

Credit: Miriam Berkley

Credit: Miriam Berkley

One of the hallmarks of his writing is his ability to put his audience in vivid, sensory-filled spaces. Sometimes that is a tobacco field: “The earth, dark and loamy smelled not of fertilizer and chemical products, but of rainwater, dead leaves, earthworms and something like peace.”

In other essays it is a boxing gym in uptown Manhattan or under an oak tree when it is struck by lightning. “It is God’s hammer slicing through the sky. The Earth rocks. Graves shake. Hearts and time stop. The sound of over 3 million volts of electricity lancing down from the sky is a different sound. Thunder booms — the sound of electricity-cleaved air rushing back together.”

An unabashed fan of science fiction, Kenan’s essays sometimes take unforeseen but delightful turns, and he approaches his explorations of Blackness and “Star Trek” with the same ease and efficacy as he approaches a scene about his mother feeding him a mess of tender greens on the front porch of their homeplace.

Kenan’s ability to hold so many literary and pop culture references at once is an achievement and one that he performs repeatedly in the later sections of the book. Boxing, space operas, Eartha Kitt and Richard Pryor have their place. Toni Morrison, Isaac Asimov, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Zora Neale Hurston get their mentions. The author that gets most of his attention is Baldwin, and it is fascinating to witness Kenan engaging with and tugging on some of the ideological concepts of his forerunner.

He is at turns wry and self-aware: “By the time I met Baldwin in the fall of 1984 I had ‘discovered’ his essays in the way Columbus discovered North America,” he writes in “The Good Ship Jesus.” In “Come Out the Wilderness” he examines his hesitation about moving to Harlem without being self-righteous or defensive: “to be sure, my discomfort had little to do with the reality of my living situation and more to do with the realty of my mental state, with the real estate of my mind … how precarious a thing is identity. However, at the time I had to keep asking myself: What is Black identity?”

By the time the reader makes it to the treatise on Gordon Parks and perspective, it is clear to see what Kenan is doing — presenting the reader with many lenses before establishing how he sees things. In doing so he offers up some nuance in the subjects he works to understand, instead of the stereotypes often associated with Southern literature. The reader is meant to wonder and wander alongside Kenan as he parses through the ephemera that comprise his life and work.

If there is one drawback of the book, it isn’t with Kenan’s writings but rather with how the essays are couched. There is little signaling in the text about when these pieces where written, where they first appeared and why they were written.

They span from 1997-2020 and each one is a gem. However, his relationship to Black identity, his Southerness, his sexuality and the writing of his forerunners changes over time. The pieces aren’t presented in chronological fashion but are instead grouped by theme — which is fine — but it’s hard to keep up with where Kenan is in the evolution of his relationships to those subjects and people. Guideposts would be helpful.

Toward the end of his life, Kenan appears prescient as he begins unpacking many of the moral crises related to race, sexuality and identity that are now widening the rift in America’s cultural and political landscape. “The coming war will not be about the monuments but about mentalities,” he says in “Letter from North Carolina: Learning from Ghosts of the Civil War,” written as Confederate monuments were being removed around the South.

The collection closes with a piece called “Letter to Self.” He speaks urgently: “You have the power to define yourself — remember that power; take control. It’s like a superpower, really, to be whom you want to be, to do what you want to do, to fly where you want to fly.”

At a tumultuous time when many readers are turning to books for inspiration on how to survive unprecedented times, Randall Kenan has this to say: “even ghosts can teach us a thing or two.”

NONFICTION

“Black Folk Could Fly: Selected Writings”

by Randall Kenan

W.W. Norton & Company

272 pages, $27.95