Stacey Abrams, a burnt '56 flag, and that feeling of deja vu

That déjà vu feeling just got a bit stronger.

Late Monday, the Democratic campaign of Stacey Abrams confirmed that, as a firebrand at Spelman College, the future candidate for governor participated in the barbecue of the ’56 state flag and its Confederate battle emblem.

Let us be clear: This was June 1992. Only a few weeks earlier, Zell Miller had begun his unsuccessful attempt to pull that same flag down. “We need to lay the days of segregation to rest, to let bygones be bygones, and rest our souls,” Miller had said. “We need to do what is right.”

If a young African-American woman couldn’t one-up a sitting Georgia governor over Confederate symbolism, she wasn’t going to have much of a future in politics. And a spokeswoman for the Abrams campaign on Tuesday noted that the demonstration wasn’t just peaceful, but properly permitted.

This isn’t a huge bombshell. Abrams made her position on historic secessionists well-known last year, when she called for the removal of the giant Confederate figures carved into the side of Stone Mountain.

In any case, if you’re still pining for the restoration of a flag that was intended as a middle-fingered protest against racial integration, it’s very likely that you weren’t going to vote for a black woman anyway.

Which isn’t to say that this revelation about Abrams is insignificant. Because it drives the narrative of this year’s race for governor deeper into already familiar territory.

On Monday, Republican Brian Kemp held a pair of events in suburban Cobb County with U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla. – territory that Rubio won in the 2016 presidential primary.

On Tuesday evening, Kemp appeared at the Atlanta Press Club debate in midtown Atlanta, at the studios of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Both events were notable exceptions in the GOP nominee’s schedule.

On Wednesday, Kemp reverts to form with a three-day, 20-stop bus tour of small-town Georgia. The first destination is the Piggly Wiggly in Jeff Davis County.

We’ve told you time and again of Abrams’ untested strategy for winning on Nov. 6, by drawing to the polls thousands of younger voters and voters of color – people who normally don’t participate in mid-term elections, and who certainly won’t blink at news that she scorched a Confederate symbol 26 years ago. Nov. 7 will tell us whether it worked.

Meanwhile, Kemp is working from a blueprint that has become almost standard for statewide Republicans. Yes, there are some elements in his campaign that were stolen from President Donald Trump, who is in his corner.

But the playbook was written in 2002 by Sonny Perdue, who became Georgia’s first Republican governor by beating the Democratic incumbent who had finally done what Zell Miller couldn’t. Gov. Roy Barnes had brought down the ’56 state flag.

In September of that year, Perdue and his campaign minions were headquartered in north Fulton County, close to the southern bank of the Chattahoochee River.

In that office, Perdue walked me through his plan for making history: He would concede a split with Democrats in metro Atlanta, but run up the score in rural Georgia. Specifically, he would target the 70 counties that had been won by Barnes in 1998, but had also voted to re-elect U.S. Sen. Paul Coverdell, a Republican, on the same ballot.

None of those counties were in metro Atlanta.

My superiors weren’t particularly impressed with Perdue’s plan. The piece on his strategy was buried on a back page with the obituaries.

Creating the skepticism was the fact that Perdue had anchored his strategy on a segment of Georgia’s population – white, rural voters – that was slowly disappearing. That November, we would learn that a population that feels its influence slipping away may be indeed be shrinking in numbers – but becomes far easier to unite, especially if one has the right hot-button message.

We would learn this again in November 2016, when much of metro Atlanta went blue, but Trump racked up extraordinary numbers in rural Georgia. “If you live in Marietta and you’re a Republican and you’re part of the establishment, you still think you’re the center of the Republican Party,” one party veteran would say when the dust settled. “But it’s shifted under their feet.”

Yet it was the 2002 race that provided the foundation, then and now. There were other issues, certainly. But it was Barnes’ removal of the ’56 flag that became visceral, interpreted as a cultural threat by a significant number of white Georgians. (Perdue promised, but as governor couldn’t deliver, a statewide referendum on the ’56 flag and its Confederate emblem.)

Other topics are being used to drive white rural voters together in 2018 — witness Trump’s constant pointing to a caravan of Central American refugees who remain a thousand miles away from the Texas border. Kemp himself often characterizes the race for governor as a contest for “the soul of the state.” And using a vague, “buried” sentence in a lawsuit, he has accused Abrams of inviting illegal immigrants to the polls.

But it is also clear that Abrams’ very persona, in some quarters, is now considered a unifying cultural threat on par with the flag that was burnt in ’92, and lowered in ’01. We are united not by what we are for, but what we fear.

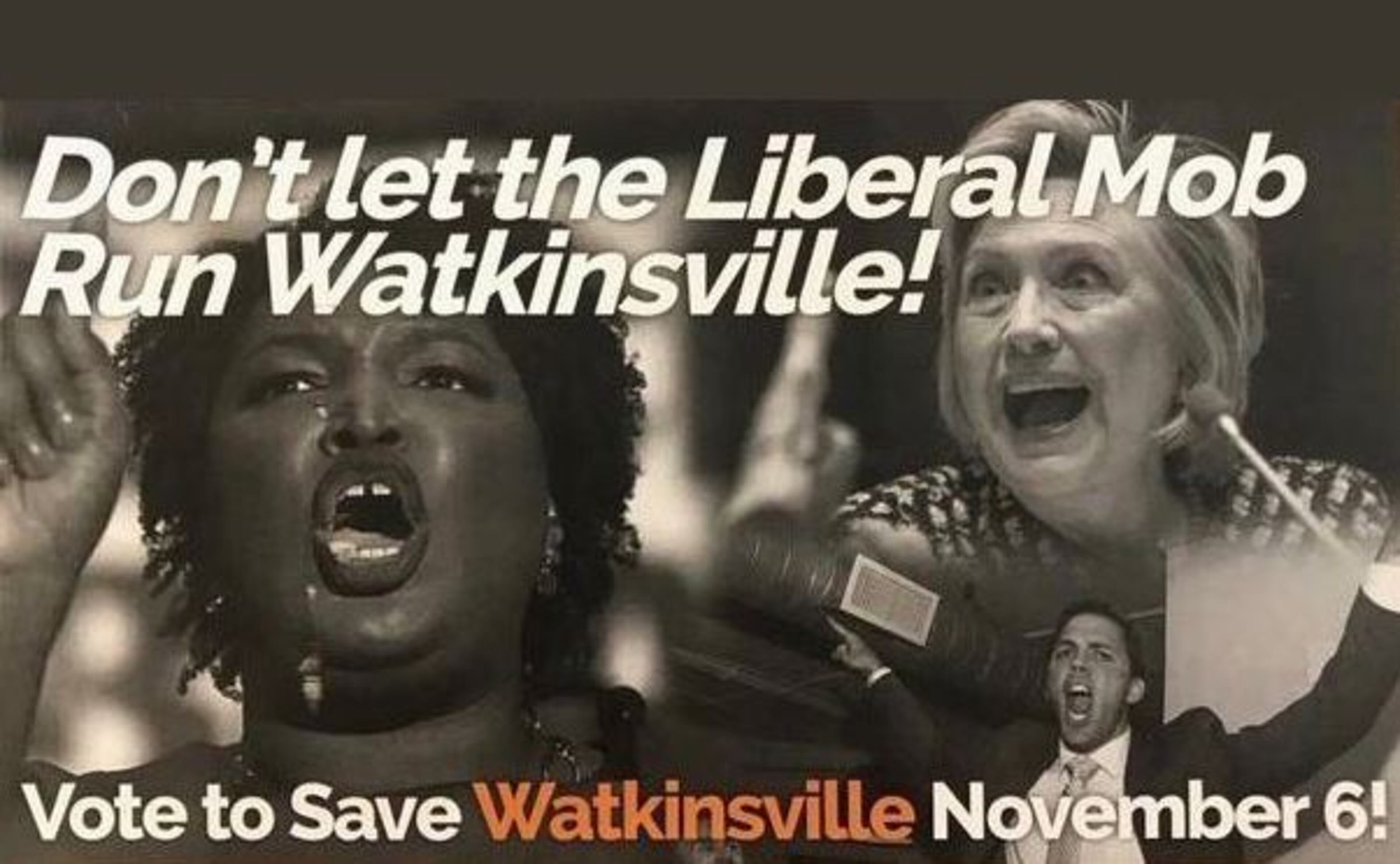

An anonymous flyer came our way over the weekend, dominated by a darkened image of Stacey Abrams and a dire headline: “Don’t let the liberal mob run Watkinsville.”

The flip side of the flyer made clear that this had nothing to do with the race for governor. Abram’s image was being used to drive voters in a trio of city council races in rural Georgia.

I would say this is déjà vu all over again, but we haven't been here before.