Remember when we were lifting our spirits with loaves of homemade sourdough during the early days of the pandemic? It was only 23 months ago, but it feels like a lifetime.

Cooking and baking have been reliable mood boosters during COVID-19, but pots, pans and muffin tins aren’t bringing me the pleasure they normally do. Cold weather, gray skies and barren trees are downers. I worry about work and family — frankly, the whole human race. And, this darn plague continues to rain down gloom and doom. Sometimes, a score of 2/6 on Wordle is the singular bright spot of the day.

My culinary creativity has been so subpar and uninspired that my husband kindly has tried to pick up the slack in the kitchen. The other day, he came home from the grocery store with a package of fake meat and the grand idea to make stuffed biscuits. I don’t know where he got his recipe, but the brown shaggy blobs that came out of the oven were as appealing as hardtack.

Yet, when I think about it, those Impossible beef-filled, stone-solid biscuits were wholly appropriate for the moment. Hardtack long has been survival food, and we’re all just trying to survive everything right now — from a global public health crisis to financial hardship to wildfires and bomb cyclones.

Apparently, hardtack remnants have been discovered that are more than 6,000 years old. And, the recipe for this ancient survival bread hasn’t changed much since the before-times. Made from flour, water and salt, the dough had holes poked in it (a process called “docking”) to make sure the cracker stayed flat, then baked for a long time, to remove the moisture. Folks might have had to choke it down, but it provided nutrition, transported easily and lasted for eternity.

I wonder if hardtack was a staple for the poor souls living in 536 A.D., the year that Harvard University medieval scholar Michael McCormick nominated as the worst for folks on Earth. You might think that the 2020s are uncertain times, but 536 A.D. takes the cake. The misery began with a volcanic eruption in Iceland that spread ash across the northern hemisphere. Parts of Europe, the Middle East and Asia didn’t see the sun for 18 months. (Think about that, all of you suffering right now from seasonal affective disorder!) Temperatures plunged. Crops failed. Starvation ensued.

Two more volcanic eruptions, a few years later, led to the coldest temperatures in 2,300 years. Of course, a bubonic plague just had to break out, and pile on the despair. One-third to one-half of the population of the eastern Roman Empire died from the plague of Justinian — as many as 50 million people. Happy times.

It makes sense that hardtack, as a food of survival, also is a food of war. The Codex Theodosianus stipulated that, during expeditions, a Roman soldier should be supplied with rations of hardtack, called buccellatum, as well as bread, wine, vinegar, bacon and mutton. It was a very exciting menu: hardtack, mutton and vinegar for two days in a row; with bread, wine and bacon on the off day. Ad infinitum.

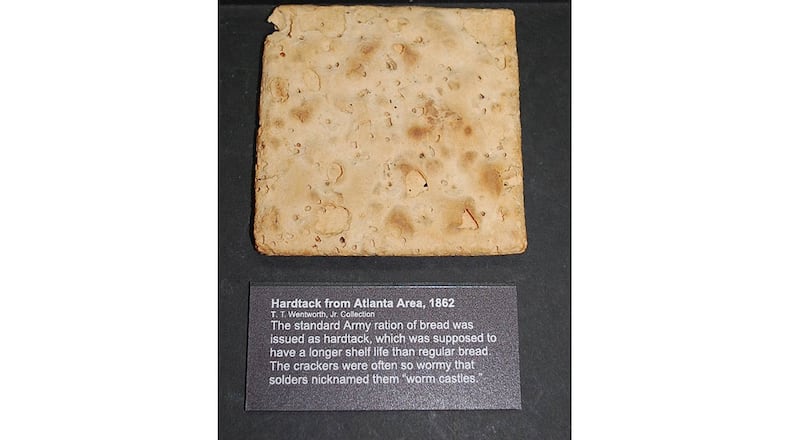

What was good enough for Roman legions was good enough for crusaders, and even soldiers during the American Civil War, where hardtack earned the nickname “sheet iron crackers” and “tooth duller.” As if being rock solid wasn’t enough, it would get moldy, and insects sometimes would lay their eggs in it, hence another moniker: “worm castles.”

On display at the Pensacola Museum of History at the University of West Florida is hardtack from the Atlanta area that dates to 1862. I wouldn’t risk a dentist trip to bite into that piece of history, but there is a guy — he goes by the handle Steve1989 — who makes a hobby out of eating old military rations. You can find a YouTube video of him eating hardtack from a Civil War equivalent of today’s MRE (meals ready to eat). “We got a really special one this time,” he said, before biting into a 153-year-old cracker packaged by G.H. Bent Co. of Milton, Massachusetts. He described the relic as smelling — and tasting — like old mothballs and library books. Delicious.

Soldiers did try to doctor them up. Union soldier John Billings described in his 1887 memoir “Hardtack and Coffee or, the Unwritten Story of Army Life” how men would crumble the crackers into a pot of coffee to soften, which had the added benefit of killing the weevils that lived inside them. The little buggers then would float to the top, and the soldiers would skim them off. Other resourceful military cookery saw troops toss hardtack into soups. If bacon fat or lard was to be had, they could fry it, to make “skillygalee.”

Getting your hands on packets of hardtack is just a click away. I found plenty of brands on Amazon — along with other best-selling, “just in case” edibles perfect for an apocalypse, including butterscotch-flavored “survival tabs,” described as being able “to supply the body with all the daily essential vitamins and minerals needed when facing uncertainty” — and with a shelf life of 25 years. Sold!

Ah, but what about the blasted supply chain that’s causing manufacturing disruptions and delivery delays? Will the hardtack even arrive in time?

Drastic times call for drastic measures. I need my husband to kick his biscuit-making into high gear. I am not going to get caught unprepared like those suckers in 536 A.D.

Sign up for the AJC Food and Dining Newsletter

Read more stories like this by liking Atlanta Restaurant Scene on Facebook, following @ATLDiningNews on Twitter and @ajcdining on Instagram.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured