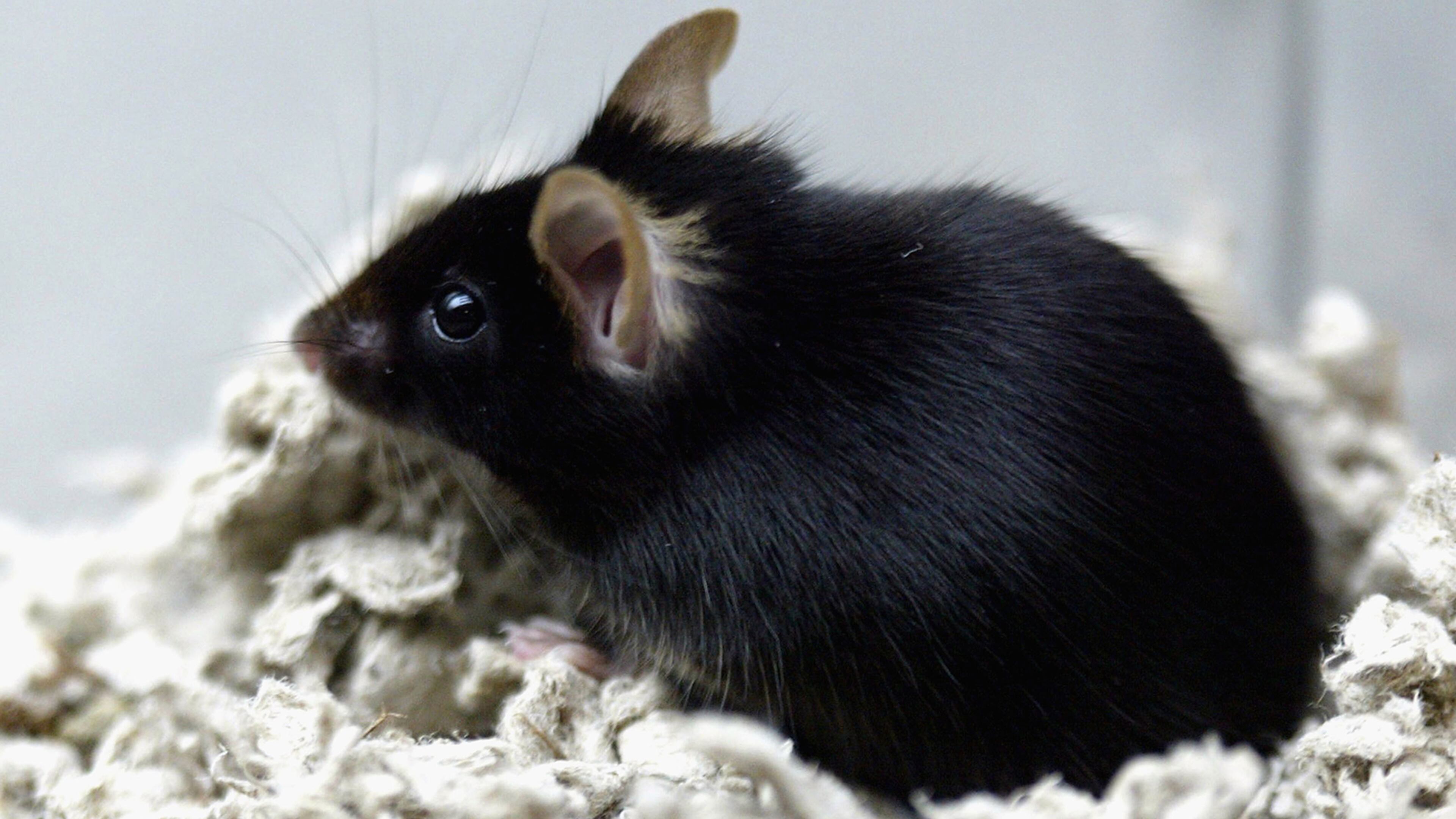

Scientists created stuttering mice to help people who stutter

- Couple found dead in Tennessee hot tub

- WATCH: Brothers convince sister of zombie apocalypse after wisdom teeth surgery

- Man goes in for routine dental surgery, wakes up with no teeth

- Baby dies on first day at daycare

- Mom stabs crying 3-month-old daughter with kitchen knife, police say

That's the sound of a mouse stuttering, and it could be the key to developing treatments for stuttering in humans.

"When we were presented to my parents for the daily viewing, she'd pinch me so that I'd cry and be handed back to her immediately," said Colin Firth in "The King's Speech."

Although many still believe stuttering is caused by environmental factors — timidity, anxiety, childhood development — scientists now know biological factors are most often the cause. In fact, scientists have been able to find a specific gene mutation in some people who stutter.

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis grew mice with that same gene mutation; one of the researchers describes what they found: "We found abnormalities — not only abnormalities in their vocalizations — but abnormalities relatively akin to human stuttering." In other words, the mice were doing the rodent equivalent of human stuttering.

Knowing the exact gene mutation responsible for a disorder potentially means being able to target that mutation for treatment.

But human genetics is incredibly complex, and the gene in which the mutation exists is involved in a whole lot more than just whether or not someone stutters.

Researchers don't quite know how the gene is linked to speech, but they do know the gene is involved in cellular digestion. "It's kind of crazy that this gene that's involved in digesting the garbage in your cells is somehow linked to something so specific as stuttering," said Timothy E. Holy, Ph.D.

And the study's senior author says that makes finding a treatment more difficult. "The apparatus for the cellular housekeeping is as old as the hills. ... How you have a mutation in those general pathways where the only known effect on people is causing them to stutter is really quite a mystery," Holy said.

This video includes clips from The Weinstein Company, TEDx Talks, Ethan O'Brien / CC BY 3.0 and Alex Raines / CC BY 3.0.