The Alday family murders are still notorious in rural southwest Georgia, even after a half-century.

On May 14, 1973, escaped prisoners from a Maryland work camp massacred members of a Seminole County farming family who had interrupted a burglary.

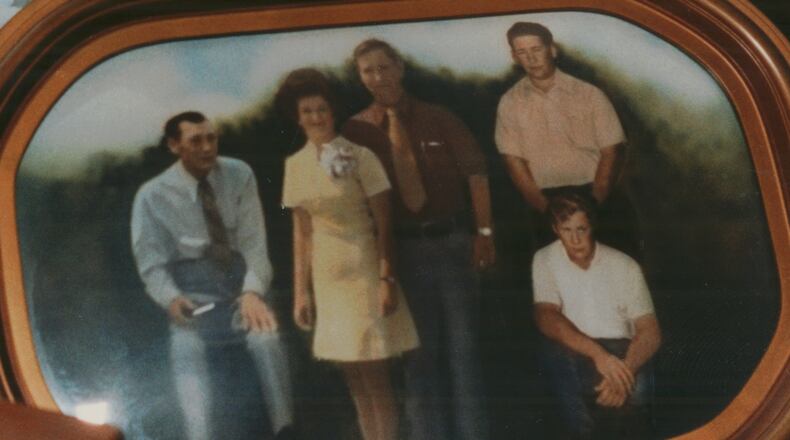

Ned Alday, 62, and five members of his family were shot to death: three sons, 35-year-old Jerry, 30-year-old Chester and 25-year-old Jimmy, as well as Ned’s 57-year-old brother, Aubrey. The body of Jerry Alday’s 26-year-old wife, Mary, was found in a wooded area, shot in the back. She also had been raped.

Five of the Aldays were shot execution style, according to police and court testimony, in Jerry Alday’s trailer about a quarter-mile from Ned Alday’s home. The Aldays farmed in the Spring Creek community, not far from the Chattahoochee River and Georgia’s border with the Florida panhandle.

The suspects were captured in West Virginia five days after the slayings. Three were escapees from the Maryland work camp: Carl Isaacs, 19; his half-brother, Wayne Carl Coleman, 26; and George Elder Dungee, 35. A fourth, Isaacs’ teenage brother, Billy Isaacs, was not an escapee but was traveling with them.

Bill Montgomery, a reporter who covered the Alday killings and the suspects’ trials for more than three decades, said the men were shaped by “foster homes, reformatories and prison.”

When they stopped at the Georgia farmhouse, they were in a stolen car that they planned to drive to Florida, he wrote in 1986, “to see the ocean.”

“Their journey would bring them to the doorstep of strangers, to the home of a clannish, religious and self-reliant rural family,” Montgomery wrote.

Isaacs, Coleman and Dungee were convicted and sentenced to death in brief back-to-back trials in Seminole County. Billy Isaacs received a plea deal in return for testifying against the other defendants and served a 20-year prison sentence on lesser charges.

The U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in December 1985 dismissed the earlier convictions, citing “inflammatory” pretrial publicity and what was called a widespread presumption of guilt in the tiny, rural county.

Three years later, Isaacs and Wayne Coleman were again convicted. Isaacs was sentenced to death by a Houston County jury. A DeKalb County jury deadlocked on the death penalty for Coleman. In July 1988, state and local prosecutors opted not to retry Dungee, citing a new state law barring the death penalty for intellectually disabled defendants. Dungee scored 68 on an IQ test, which was determined to be borderline intellectually disabled. Coleman and Dungee were given six consecutive life sentences.

Dungee died in custody at the Georgia State Prison near Reidsville in 2006, according to the Donalsonville News. The newspaper said Billy Isaacs died in Florida in 2009. He had been paroled in 1994.

Coleman, now 77, is being held at Wilcox State Prison in Abbeville, according to the Georgia Department of Corrections.

Carl Isaacs was executed by lethal injection in May 2003, 30 years after the murders, at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison in Jackson. He was 49.

Three members of the extended Alday family, including Faye Barber, daughter of slain family patriarch Ned Alday, witnessed the execution, the AJC reported at the time. More than 60 relatives were outside the prison, after arriving in a caravan of six cars and a bus. Eighteen state and local law enforcement officials were also on hand.

The story of that day continued:

“It’s 200 miles from Donalsonville to Jackson, Georgia, but it’s taken us 30 years to get here,” said Paige Seagraves, Ned Alday’s granddaughter.

Isaacs declined to ask for a final meal and was given the “regular institutional tray” of pork and macaroni, pinto beans, cabbage, carrot salad, dinner roll, chocolate cake and fruit punch. He pushed the meal away.

Isaacs’ last appeal to avoid execution argued that spending nearly three decades on death row is “cruel and unusual” punishment. The U.S. Supreme Court briefly stayed the execution shortly before 7 p.m. but minutes later, without comment, allowed the death sentence to be carried out.

Jack Martin, Isaacs’ defense attorney, witnessed the execution. “I just saw a person being killed by the citizens of Georgia,” he told reporters. “We have become one with the killers, and we are all the lesser for it.”

-This story was written and edited from earlier reporting by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

About the Author