Asians have long, complex history navigating Georgia’s racial divides

Nearly 100 years ago, as a wave of nativism enveloped the country, a DeKalb County state representative introduced a bill that expanded the ban on intermarriages in Georgia.

Under the legislation, which became law in 1927 and remained on the books for 40 years, no one with an “ascertainable trace of either Negro, African, West Indian, Asiatic Indian, Mongolian, Japanese or Chinese blood in their veins” could marry a white person.

Much has since changed in Georgia, but difficult questions about race haven’t gone away.

Authorities haven’t settled on a motive for the March 16 killings of eight people, including six Asian women, at three metro Atlanta spas by a 21-year-old white male suspect.

Many Georgians of Asian descent believe the shooting spree was a racially motivated hate crime. To some, the violence on March 16 was a reminder of their status as perpetual outsiders in a part of the country where race is so often discussed in terms of Black and white.

It is a view that some historians say is reinforced by more than 150 years of Asian American experience in the region.

Metro Atlanta today is home to a fast-growing and diverse Asian community, representing 6% of the population and spanning about two dozen nationalities, from more established Chinese and Indian families to more recent arrivals from South Korea, Vietnam and Cambodia.

Some say they have long felt trapped in a gray area, alternately ignored, targeted and lauded for being a “model minority.” That they are not fully accepted as American — even if they’re citizens or have spent their entire lives here — and at the mercy of shifting political winds and the whims of the white majority.

“The bigger picture is not going to change until there’s at least a growing, deeper acceptance that this anti-Asian hate and violence is an outcropping of racism, not something else,” said Helen Kim Ho, a Gwinnett-based attorney of Korean descent.

“Locally we’re still fighting for people to even embrace the concept that racism is not just between white and Black people,” added Ho, who founded an Asian civil rights group.

‘Constantly being on edge’

For much of Georgia’s history, Asians remained a minuscule segment of the population. Because of that, white leaders largely didn’t view them as a threat to the racial order, according to researcher Daniel Aaron Bronstein, who wrote about Georgia’s early Chinese communities in the 2013 anthology “Asian Americans in Dixie.”

For the few Asians who did live in Georgia before the 1960s, they quickly had to navigate a system that was built on white dominance over Black people.

Indeed, many of Georgia’s first Asian residents were Chinese laborers hired to fill the void created by the abolition of slavery. In the years following the Civil War, wealthy plantation owners in need of cheap labor hired East and South Asian indentured workers that the British and Spanish empires had used for years to harvest sugarcane in the Caribbean.

Those workers, known derogatorily as “coolies,” were viewed with suspicion particularly on the West Coast, where poor whites argued they took away American jobs building the railroads and pushed down the price of labor. Nevertheless, in 1873 a construction company hired 200 laborers from south China to widen and deepen the Augusta Canal.

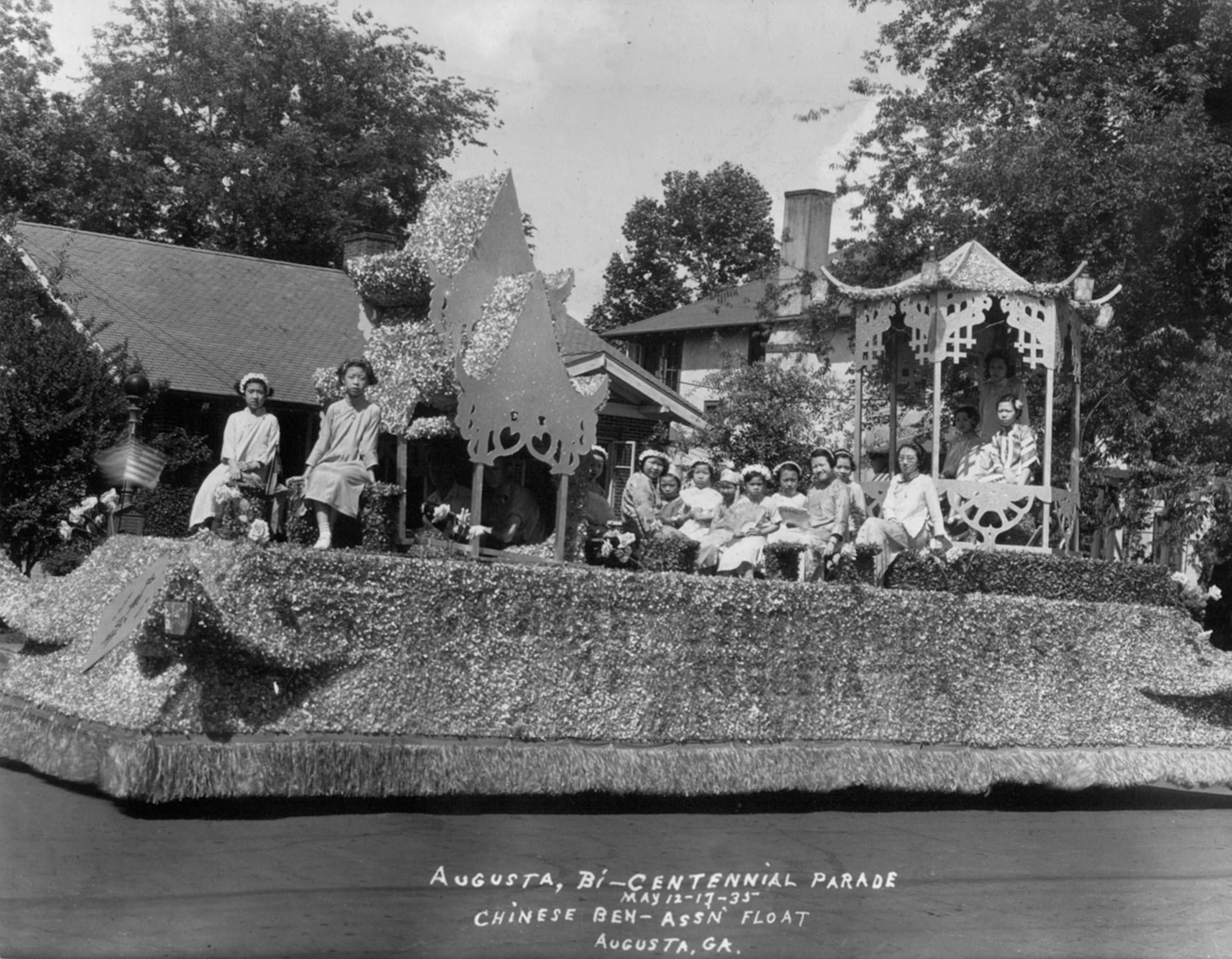

Raymond Rufo, a lifelong resident of Augusta and historian for the city’s 94-year-old Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, said the laborers were viewed largely as “curiosities” by local residents.

“Nobody had seen Asians before in this part of the country,” said Rufo, highlighting an Augusta Chronicle story from the time that marveled at the hardworking men who kept their living expenses to a meager $7 a month while sending the remaining $28 they earned in gold back to their families in China.

After the project was done, most of the workers left the region but a few stayed, opening up grocery stores and a tea shop in Augusta. Chinese migrants also operated laundry businesses in Savannah and Atlanta, often in Black neighborhoods where whites didn’t want to do business. In 1894, 13 towns in Georgia reported at least one Chinese resident.

Because of an 1875 immigration law that restricted Chinese women, whom the U.S. government believed were likely prostitutes, most shop owners were single men.

They mainly socialized with one another while steering clear of Black residents, mindful of what the latter could do for their social standings under Jim Crow, according to some historians.

“They really did try to stay to that middle ground, keep their noses down, keep moving forward and try to distance themselves from African Americans as much as possible,” said Stephanie Hinnershitz, a research adviser at Alabama’s Air University who wrote a book about Asian American civil rights in the South.

In the early decades after the Civil War, Asian immigrants enjoyed some privileges that Georgia’s Black population — and people of Asian descent in other Southern states — couldn’t. That included attending white schools, riding in the white sections of railroad cars and being classified as white on state issued driver’s licenses.

At the same time, according to historians, they were rarely accepted as part of the white community, and access to economic, political and social opportunities was unpredictable.

“It really did vary,” said Hinnershitz. “But something that kind of tied all those experiences together was not knowing where their place was and constantly being on edge. They’re accepted one day, they’re seen as good economic partners, but that could turn at any moment.”

That didn’t stop some Asian leaders from making gestures to win favor.

Leslie Bow, a University of Wisconsin–Madison professor who’s written about how Asians lived under Jim Crow, said some Chinese American civic groups in the South donated to hospitals even if they were sometimes barred from using those facilities due to segregation.

In some instances white elites aimed to build bridges with Asians.

Chris Suh, an assistant professor of history at Emory, said the university was one of several southern Methodist schools that recruited elite students from East Asia in the 1880s and 1890s to train as missionaries in the southern conservative tradition.

“This is a time when Blacks and Jewish Americans are being persecuted, and you randomly have these Asian elites who are invited to dinner parties with the most influential southerners because they’re Christian, because they’ve conformed to what the white Christians believe is a great way for a non-white person to behave,” said Suh.

But Suh said most students were keenly aware there were lines they should not cross — mainly not to marry white women.

Records of lynchings and brutal violence against Asians from that time are spotty in Georgia, but many of the known instances of intimidation involved people suspected of relations with white women.

William Loo Chong, a grocer and tea dealer of Chinese descent, and his business partners were threatened with violence and told to leave Waynesboro, Ga. in the early 1880s after white residents found out Chong was married to a white woman, according to Bronstein.

One Georgia case involving a white Fulton County teenager and a Filipino yo-yo exhibitionist accused of raping her made it all the way to the state Supreme Court in 1933.

But there’s also evidence that the Chinese community in Augusta, at the time the largest in the state, had enough political clout to stop some attempts to roll back their rights, even when Jim Crow was in full swing.

“People didn't know what to do with me. I wasn't white, but I wasn't Black, and on top of that I was Hindu. What is that?"

In the late 1880s, the Augusta City Council rejected an effort to block business licenses to Chinese shop owners after white merchants complained they couldn’t compete. Augusta’s mayor personally reaffirmed the council’s ruling after Chinese immigrants locked themselves in homes amid fears of violence, Bronstein wrote.

Nearly 50 years later, the Chinese community and allies blocked a bill in the state Legislature that would have defunded white public schools that enrolled Chinese students. That effectively allowed Chinese children to attend white schools in Georgia, unlike in Mississippi, where the U.S. Supreme Court had upheld a decision that defined Chinese students as “colored” a few years earlier.

Bigger community, still apart

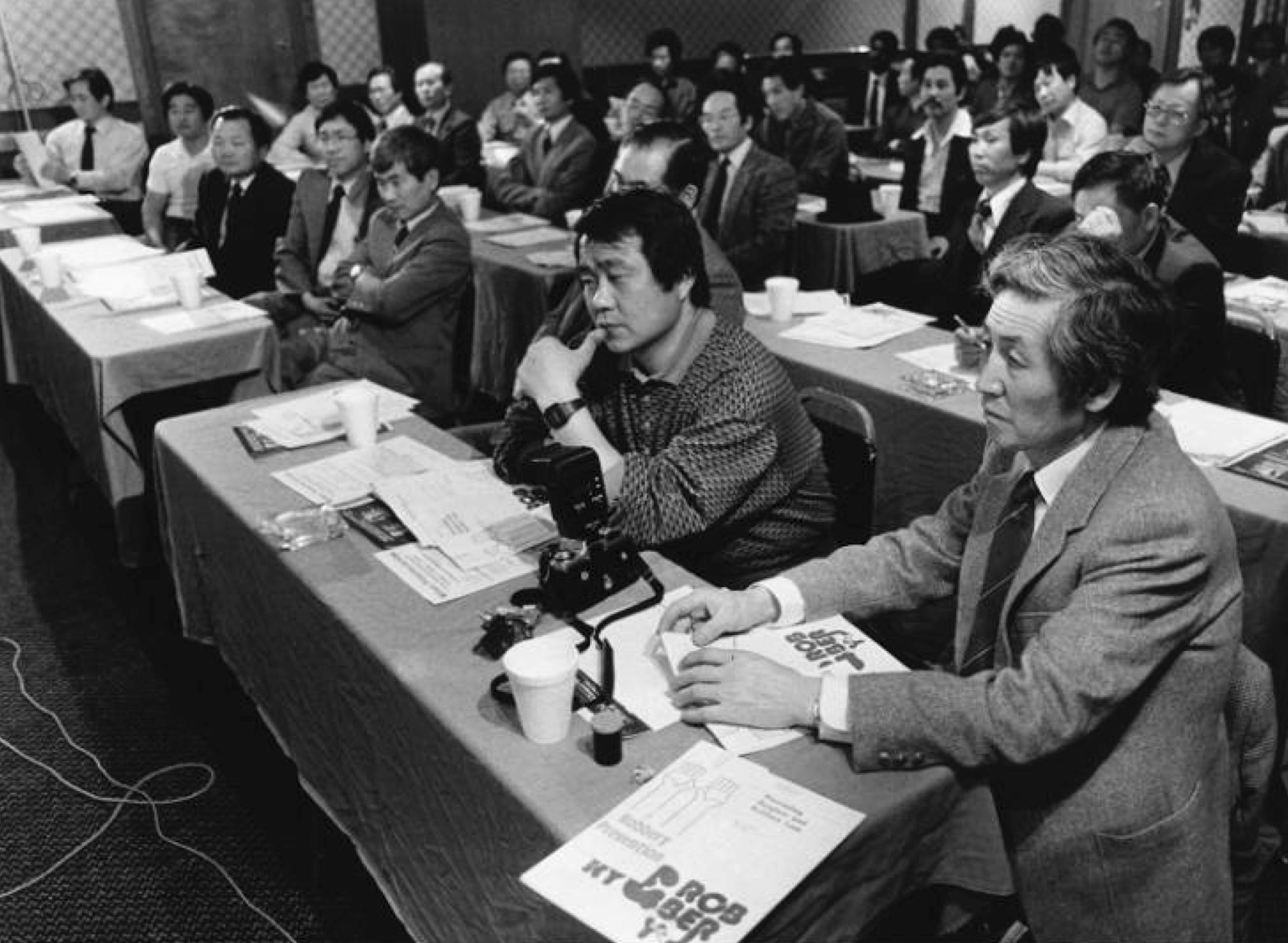

The 1960s brought major changes to Georgia’s immigrant communities. The Civil Rights Act barred discrimination, and a year later Congress overhauled national immigration quotas, opening up more opportunities for family reunification. The new system also prioritized professionals such as doctors, engineers and scientists. Metro Atlanta, with its universities and large hospital systems, became a magnet.

But some who grew up here in the subsequent decades remember being bullied and harassed for being different.

“People didn’t know what to do with me,” said Khyati Joshi, an Indian American professor at Fairleigh Dickinson University who grew up in Mableton in the late 1970s and 80s and co-edited “Asian Americans in Dixie.” “I wasn’t white, but I wasn’t Black, and on top of that I was Hindu. What is that?”

Top five countries of descent for metro Atlanta’s 343,760 Asian residents:

India: 125,724 (36.6%)

China (excluding Taiwan): 48,684 (14.2%)

Vietnam: 46,719 (13.6%)

Korea: 45,644 (13.3%)

Pakistan: 11,824 (3.4%)

Source: Atlanta Regional Commission analysis of 2019 U.S. Census data

More recent immigrants also recall feeling isolated and not welcome.

Grace Ko, a 29-year-old theology student who lives in Duluth, came to the United States from South Korea a decade ago. She remembers going into a dealership to buy a car and a salesperson providing less detailed information after realizing she didn’t speak fluent English. She says the same thing happened on a trip to buy a sofa.

“I think some Americans look down on you when they realize you are not a native speaker,” she said.

Advocacy groups say they’ve seen rising prejudice against Asians since the coronavirus pandemic, and some view comments from former President Donald Trump and his allies describing COVID-19 as the “China virus” and “kung flu” as particularly damaging. The group Stop AAPI Hate recorded nearly 3,800 “hate incidents” against Asians across the country between March 2020 and February 2021.

Ho, the Gwinnett attorney, describes “being stared down with hatred” by patrons at the grocery store early last year when she was an early mask adopter. She said it’s the latest in a pattern she’s experienced her entire life living in the South.

“Getting that weird look. Having my children looked down upon. Being told to step back. The ‘ching chong’ China comments,” she said. “It’s always been there.”

Staff writer Matt Kempner contributed to this article.