Seattle plane theft: How does Atlanta airport handle security risks?

The Friday night theft of a commercial airliner from a major airport by an airline worker, who then flew the plane around the Seattle area and crashed it into an island, is prompting new scrutiny of aviation security and screenings of workers.

In the hours and days following the harrowing event involving an empty 76-seat Horizon Air Q400 turboprop plane and the ground service agent who handled baggage and towed aircraft, there are fresh questions about whether the background checks workers undergo are thorough enough. Some are asking whether such workers with access to commercial aircraft should undergo mental health screenings.

“That’s what the investigators are going to be looking for: Where were the gaps?” said Ken Jenkins, an aviation crisis consultant.

The incident is expected to prompt reviews of security procedures by federal agencies and airlines nationally.

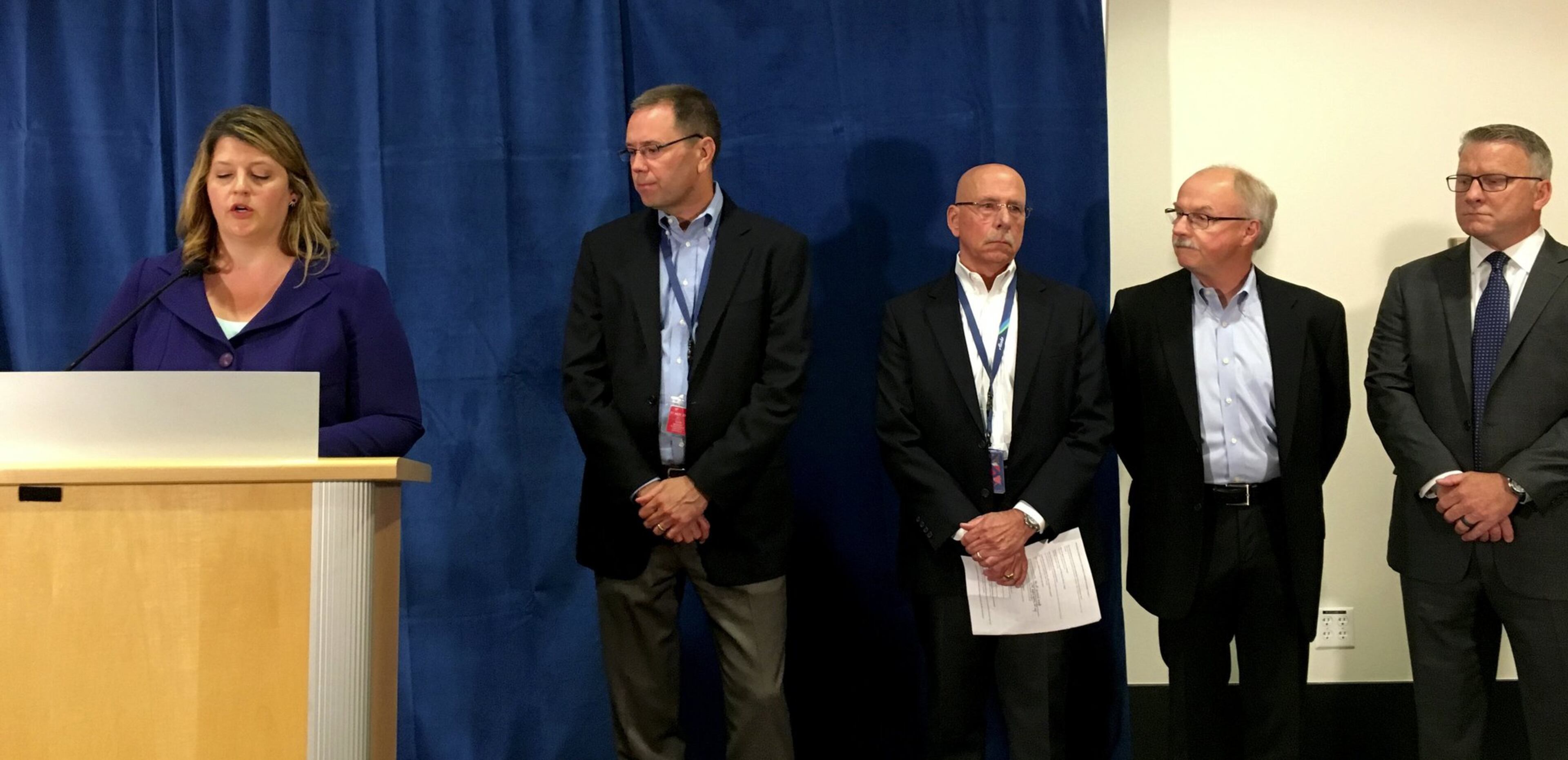

The FBI is leading an investigation and authorities have "many open questions," said Alaska Airlines CEO Brad Tilden during a Saturday press conference. Horizon Air is a subsidiary of Seattle-based Alaska Air Group.

Airline ground employees and other workers airports with access to secure areas with planes go through Transportation Security Administration background checks, including a criminal history records check and recurrent checks against a terrorist watchlist.

Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport requires an FBI fingerprint-based criminal history check of employees with badges to access secure areas, who can be disqualified for certain crimes within the past 10 years. The Atlanta airport also requires security awareness training for employees with badges.

But there are more stringent requirements for airline pilots under the Federal Aviation Administration. Pilots are also subject to a medical exam every six or 12 months, are asked questions about their mental health in a form and must disclose any physical or psychological conditions and medications or face fines, according to the FAA.

“You’re going to see an evaluating of processes and procedures to see what can be done to mitigate the risk,” Jenkins said. If something can “reduce the risk … that’s the goal.”

Some say the Seattle event was highly unusual and difficult to foresee, making it difficult to implement foolproof checks of airline workers to prevent it from happening again.

“Do you have to create more security for an event that is extremely rare, unpredictable and doesn’t follow any sort of pattern?” said Todd Curtis, an aviation risk assessment expert and founder of AirSafe.com. “It didn’t sound like someone who had some premeditated plan to do something with this aircraft. … How do you protect against human frailties? That’s an issue that goes well beyond aviation.”

And, mental health screening requirements can conflict with privacy protections, Curtis said.

Phil Derner Jr., a former airline dispatcher who started aviation website nycaviation.com, posted on Twitter: “There may be no foolproof way to totally prevent qualified, otherwise authorized people from using their job’s tools to harm themselves or others.”

But Jenkins said another major concern is how the man was able, without authorization, to push back the plane and taxi to a runway without being detected and halted.

“How did someone miss this?” Jenkins asked about the fatal disaster.

And Curtis raised questions about how large targets such as landmarks, tall buildings or stadiums full of people could be protected from an unauthorized pilot with hostile intent flying over a large city.

“Is there something reasonable that can be done?” he asked.

It’s not the first time a major incident has raised concerns about an “insider threat” among the nation’s thousands of airport workers, who have access to secure areas of airports and the aircraft that carry millions of passengers around the world.

In Atlanta, a gun-smuggling operation at the world's busiest airport involving a Delta Air Lines baggage handler in 2014 highlighted security gaps and concerns about airline workers.

That incident prompted increased background checks of airline workers.

In 2015, then-Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson said the Atlanta incident “raised questions about potential vulnerabilities regarding the screening and vetting of all airport-based employees.”

In response, the TSA boosted requirements for screening of airport and airline employees and began “real time recurrent” criminal history background checks for all aviation workers.

Hartsfield-Jackson also responded by launching new screenings of employees who work at the airport and reducing access points to secure areas.

Airport spokeswoman Elise Durham said the Atlanta airport has “led the nation” in actions “to mitigate security vulnerabilities from airport employees.”

Now, in Seattle, Alaska Air CEO Tilden said the Friday night crash “is going to push us to learn what we can from this tragedy so that we can assure this does not happen again at Alaska Air Group or at any other airline.”

Hartsfield-Jackson’s actions to mitigate security risks from airport workers include:

• Reducing the number of secured area access points from 70 to 10

• Implementing full employee screening

• Deploying more than 3,000 CCTVs to monitor activity throughout the airport

Source: Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport