Another NFL Sunday is upon us, another afternoon of noting who kneels, who stands, and who sits when the national anthem is played.

The potential for racial animus is significant, as President Donald Trump well knows. Some two-thirds of pro football players are African-American. Close to 80 percent of NFL fans are white. Team owners are a rather pale lot, too.

And yet last week, when Trump — eager to distract from the failing Alabama senate candidate he was attached to — called for owners to fire the next SOB who took a knee, the collective response from most NFL clubs was surprising. The Falcons and Arthur Blank included.

On team after team, some stood, some knelt, but arms were locked or hands linked. White and black players alike.

Most Americans would acknowledge that kneeling is an acceptable, even laudable, way to address the Almighty. But a Fox News poll, conducted after Trump's remarks in Alabama, showed that only 41 percent of Americans think it to be an "appropriate" form of protest. Fifty-five percent described kneeling as "inappropriate" — a downward shift from last year, when 61 percent condemned it.

Still, those numbers mean that many locking arms on the sidelines last week might not have agreed with Colin Kaepernick’s form of personal protest against police violence, but joined in anyway.

Trump blamed the owners. “I think they’re afraid of their players, if you want to know the truth, and I think it’s disgraceful,” the president said Thursday.

I have a better explanation: Unit cohesion. It was the sanctity of the locker room that dictated the NFL's response to Trump.

In military parlance, unit cohesion is the ability of a group to ignore and even accept individual differences for the sake of collective survival and the mission beyond, be it the Super Bowl or the next hill.

Given that football, with all its gladiatorial aspects, is the most militarized of American sports (ask George Carlin), this is not a great leap. State Rep. Scott Holcomb, D-Atlanta, a former Army lawyer, quickly saw the connection.

“You fight for something bigger than yourself, but when you’re there on the battlefield, what’s most important are the people who are right next to you,” he said. “That camaraderie, that tightness, I think it’s a more powerful force than the bigger, flag-waving stuff that gets talked about.

“In many ways, it’s a family-type thing. You can say bad things about your brother, but Joe better not. Because you’ll beat up Joe,” Holcomb said.

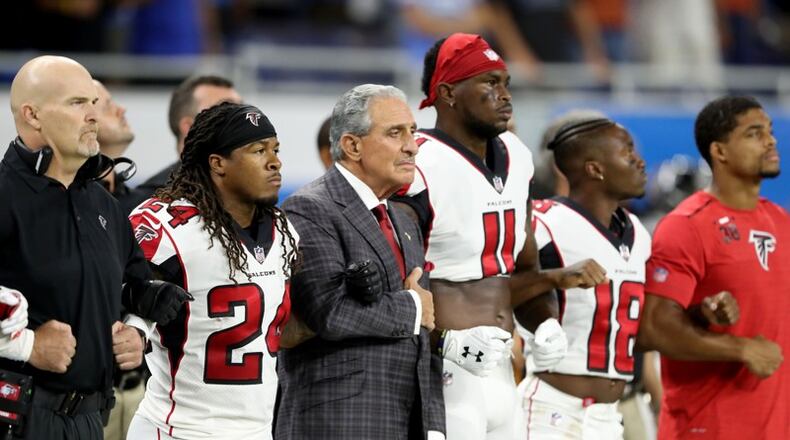

Sun Tzu speaks of it. Carl von Clausewitz, too. Unit cohesion travels horizontally within the ranks, but also has a vertical aspect. Even generals are required to participate. Which is why you saw Blank sandwiched between Julio Jones and Devonta Freeman in Detroit last Sunday.

Trump is familiar with the concept. This summer, he justified a ban on transgender troops in the U.S. military because, he claimed, it posed a threat to unit cohesion.

Unit cohesion was cited as a reason for segregating black troops from white ones, until Harry Truman said otherwise. For keeping women out of combat zones. For making “don’t ask, don’t tell” one of the most peculiar phrases to come out of the 1990s.

Military texts will tell you that cohesion isn’t just about unity. It is the absence of isolated individuals who might elsewhere be dismissed as the unwanted “other.”

In Huntsville, when Trump profanely called out anthem-kneelers, he was calling for the creation of pariahs within the ranks of dozens of NFL teams. Owners certainly understood the implications. After all, theirs is a $75 billion commercial venture. But players did, too.

“The locker room, that’s not a segregated place. That’s a place of unity,” said Dewey McClain, the only former NFL player I have in my cell phone. McClain, 63, was a Falcons linebacker for four years before moving on to the United States Football League.

He’s now a president of the Atlanta North Georgia Labor Council and a Democratic state House member from Lawrenceville.

“If anybody’s out of place, a play falls apart,” McClain continued. “You have to trust and believe in the other fellow to do his job. If I can’t trust you, that really means I can’t play with you. And once you lose trust, it’s very hard to get it back.”

It’s really pretty simple, McClain said. Allow a culture war to explode in the intimate confines of a locker room, and you can kiss a winning season, even the Super Bowl, good-bye. And all the bonuses that come with that success.

Many of you are ticked off by whiny millionaires, and I get that. But we allow a certain billionaire in charge of the federal government to complain daily about the unfair treatment he endures. We ought not discriminate against the less fortunate.

More importantly, in the NFL we now have the example of an American institution that, rather than becoming bogged down in an unwinnable distraction, has decided to proceed with its mission and throw points up on the board.

You might even call this attitude “congressional” – but only if you wanted to start a brawl in the locker room.

About the Author