In the last known interview Rich Homie Quan gave before his passing, the Atlanta rapper is seen smiling.

He answered questions about his favorite television shows, which include “Boy Meets World” and “The Proud Family.” He also shared the possibility of releasing new music with Young Thug, his incarcerated former partner-in-rhyme, along with plans to release a “plethora” of other freshly recorded material.

He closed the video interview with influencer Alanah Story by doing a drop for her “What’s the Story” show.

“Hopefully you continue to follow my story because it’s not over,” Quan said after mentioning he planned to follow his new single, “Ah’Chi” featuring 2 Chainz, with more music before his birthday in October. “I haven’t reached my peak.”

Quan died Sept. 5.

The Atlanta rap star, born Dequantes Devontay Lamar, was found unresponsive by his girlfriend at their southwest Atlanta home. He was 34.

Though the cause of death is unknown, this week the Atlanta Police Department released more details related to Quan’s death. A full autopsy report with results could take up to 90 business days, according to the Fulton County Medical Examiner’s office.

In the early 2010s, Quan’s hits “Type of Way,” “Walk Thru” and “Flex (Ooh, Ooh, Ooh)” brought him mainstream success, further solidifying Atlanta’s trap stronghold on hip-hop. With Young Thug, he formed the Cash Money Records duo Rich Gang, which released the 2014 hit “Lifestyle.” The simultaneous arrival of Young Thug, Future and Quan around this time marked a sea change in the city’s next generation of rap artists finding their voices.

Quan’s shocking death is a heartbreaking blow to a city’s hip-hop community already reeling from losses of several young Black artists before their time.

Local industry executives, DJs and media personalities who say Quan’s generation of artists represent the bridge between trap music’s forefathers and today’s crop of Atlanta rap voices are worried about the lasting impact of those collective losses. They are also eager to find solutions.

The issue was on Nick Love’s mind nearly three weeks before Quan’s passing. In response to a post on X from a fellow music industry executive lamenting the loss of emerging rap artists XXXTentacion, JuiceWRLD, Pop Smoke and Pooh Shiesty, Love said the topic deserves more attention.

Love said he doesn’t believe Atlanta has properly addressed losing so many prominent young rappers from the city, including Bankroll Fresh, Trouble, Takeoff, Dopeboy Ra, Lil Keed, Lil Marlo and others — all crucial links to the connective tissue between Atlanta rap generations.

Love, now senior product manager at music distribution company ONErpm, first came to know Quan when he managed Dopeboy Ra, previously known as Young Capone and RaRa, who passed away in 2023.

He called Quan a preeminent voice who helped evolve Atlanta’s trap hip-hop sound, but is now included in a list of at least 10 artists or executives Atlanta’s rap community has lost to death or incarceration since 2016.

“Think about all these videos, all these pictures, all these things we have, where there’s groups of people no longer here,” Love said. “I can go through my Instagram page and find whole pictures where there’s four or five people in the picture, and three of them are gone. That’s troubling to see because it’s like, how does that impact a city?”

Hot 107.9 radio personality Moran tha Man said losing Quan and other artists is like losing a neighbor or close friend. “In Atlanta, these are our peers for real,” the Atlanta native said.

“You could go to Edgewood Avenue, go to Our Bar, and Trouble (would) be there. You could go to Lenox Square and you might see Lil Keed. These are our people that we really had access to, and to know they’re no longer here I think it’s just traumatic for a lot of people.”

Moran first caught wind of Quan when the latter performed at University of West Georgia in 2013, months before the song “Type of Way” reshaped his career trajectory. The two connected professionally five years later during a promo run for Quan’s debut album “Rich as in Spirit.”

“It sucks that we won’t get to see a lot of these people grow old and really pass down the keys to the next generation,” Moran said.

Credit: Via White House livestream screen grab

Credit: Via White House livestream screen grab

Who or what is to blame?

After the shooting death of Migos rapper Takeoff in November 2022, Mayor Andre Dickens remarked that hip-hop culture isn’t the problem. “I do not believe that hip-hop equals violence. I grew up on the music. I’m still into the music,” Dickens posted on Instagram.

Others, including Clark Atlanta University mass media arts professor and former radio personality Brian “B High” Hightower, have different thoughts. “I’m not going to say the music is actually killing people, but it’s damn-sure not telling them to ‘get up and get out and get something,’” Hightower said, citing often-violent lyrical content in rap today while nodding to the classic 1994 Outkast song, “Git Up, Git Out.”

Hightower remembers recording Quan’s first major radio interview on April 9, 2013. He was struck by the upstart emcee’s lyrical prowess, melodic flow and honesty. He recalled Quan having the “spirit of a young Tupac,” and found his unique voice and approach more akin to the Dungeon Family than the trap.

Hightower saw the same star power in a young rapper named Future, whom he’d interviewed months prior, and believed Quan would be another positive outcome in Atlanta’s revolving door of rap talent.

That’s no longer the case, Hightower said.

“It was new artists coming out every week in Atlanta that had great talent, but these artists started getting killed and going to prison,” he said. “Now all of a sudden nobody knows how to break an artist. Nobody knows how to give nobody opportunity anymore.”

Some responsibility falls on artists, Love said, adding personal accountability should be considered. He suggests destructive decisions made by young artists typically come from outside factors.

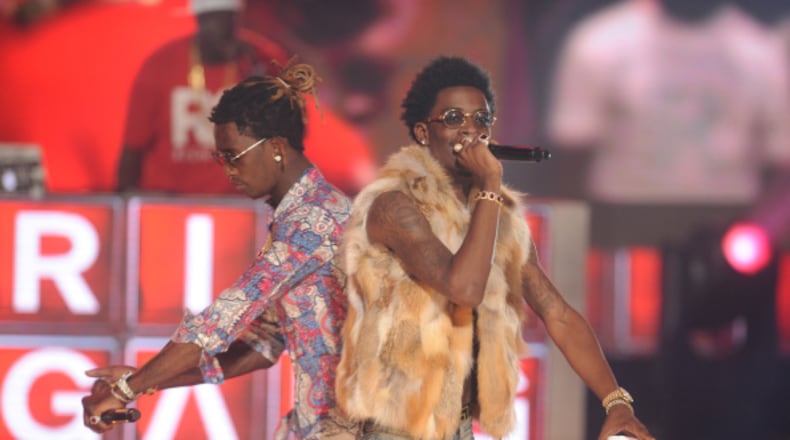

Credit: Brad Barket/BET

Credit: Brad Barket/BET

“I just wish we could all collectively find a way to embrace the people we’re fans of and show them that while they’re here,” Love said, “because some of that is depression based, some of that is just feeling unseen or unheard. That’s a lonely place to be.”

Love and Hightower both stress throwing community support behind current torchbearers such as EarthGang, JID, 21 Savage and Kenny Mason. Hightower wants more unbiased reporting from local media on hip-hop’s positive rhetoric.

Love said seeing record labels like Atlanta-based LVRN launch mental health services for artists and staff is promising. He’d like to see more efforts to educate artists and professionals on aging gracefully.

Those could be the beginnings of more solution-based discussions on preserving Black lives in Atlanta’s music community, said Love, who quipped that envisioning 60-year-old versions of your favorite rapper shouldn’t feel unrealistic.

“There needs to be conversations around it, just figuring out how to all grow and age together, in a way that’s healthy and just good for the community at large.”

This story has been updated to correct Rich Homie Quan’s age at the time of his death.

Sign up for the UATL newsletter.

Read more stories like this by liking UATL on Facebook and following @itsUATL on X and Instagram.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured