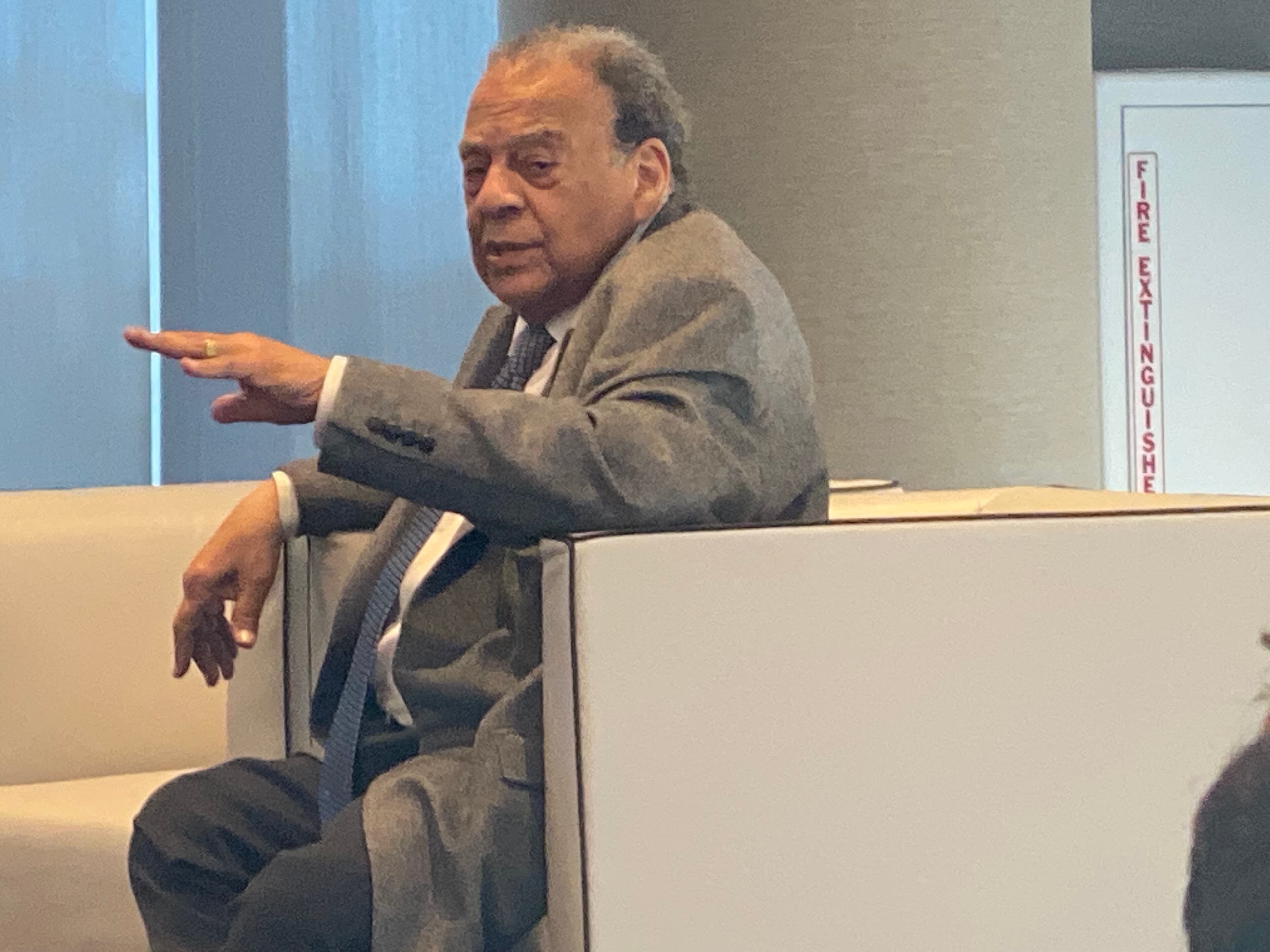

Andrew Young ‘is just getting started’ as civil rights icon celebrates 80th birthday

Published May 21, 2012

At 80, Andrew Young — who has been a civil rights giant, congressman, U.N. ambassador, big city mayor, television executive, businessman, and global entrepreneur — is finally slowing down.

At least that is what he is saying.

“I have done everything everybody else wanted me to do. I don’t have enough energy to do what I want to do and what everybody else wants me to do,” Young said. “I want to cut back on some of the obligations.”

But sitting in the office of the Andrew Young Foundation last week, he constantly reaches for his iPhone, fielding calls from business associates and people seeking political advice. He also fiddles with his iPad, looking for his 76th book to read this year. At one point, Ernest Green, a member of the Little Rock Nine, just walks in to say hello.

“I want to give back the blessings that I have received. I want to be active in my church,” Young continues. “I want to be active with black schools like Morehouse and Clark Atlanta.”

The list goes on and grows: continue to fight injustice through nonviolence, bring the government and private sector together to create jobs, open more trade routes, make movies.

“I think about big things,” he concludes.

His wife, Carolyn, is on the office speakerphone. You can almost see her shaking her head.

“Moses started at 80, so Andy is just getting started,” she says. “He has 25 to 30 more years of work to do. Birthdays are just symbolic to him.”

Symbolic or not, more than 1,200 of Young’s closest friends — including Oprah Winfrey and Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed — will be on hand today to celebrate his 80th birthday at an all-star gala at the Hyatt Regency Atlanta. Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton and poet Maya Angelou are expected to deliver video tributes.

“At 80, he has made a lasting contribution not just to the city of Atlanta, but to the nation and the world,” says U.S. Rep. John Lewis (D-Atlanta), who met Young in 1961. “He has been a voice for what is right, fair and just and America. He helped make America and the world a better place.”

Last week, Young’s office was buzzing, getting ready for the gala and gathering biographical information on him. It took a while.

He had pastored small churches in Alabama and Georgia and briefly lived in New York City, before moving to Atlanta in 1961 to become director of the SCLC’s Citizenship School program and Martin Luther King Jr.’s top lieutenant.

He was on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968. After King’s death, he ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1970. He tried again two years later and was elected to represent Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, the first black elected in the Deep South since Reconstruction.

“He was Barack Obama in the ’70s when he was elected to Congress from a majority white district in Georgia,” said Young’s oldest daughter, Andrea Young, the executive director of his foundation.

Lewis has now held that seat for 26 years.

In 1977, Carter appointed Young as the United States ambassador to the United Nations, but he was dismissed in 1979, after reports surfaced that he had held a private meeting with a Palestine Liberation Organization official. The United States had promised Israel that it would not meet with the PLO until the group recognized Israel’s right to exist.

Two years later, Young was elected mayor of Atlanta, serving two terms. After leaving office, he went on to help Atlanta get the 1996 Olympics. He built a business and philanthropic empire that stretched through Africa, and he produced television shows and documentaries, even winning an Emmy.

In the interim, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 125 honorary degrees — including ones from colleges that had declined to admit him as a student — and visited 162 countries.

“That is one of the reasons that my ideas and opinions differ from most people. I have seen the world from every aspect,” Young said.

Andrew Young, a son of the South, baptized in the hot cauldron of civil rights, probably knows more about power and influence than anyone who has ever walked Atlanta’s streets. And he says he did much of what he did reluctantly.

“I wasn’t predicted to be anything. I just followed an inner spirit and it put me in the right place and the right time,” Young said. “I didn’t want to be the mayor of Atlanta. I didn’t want to run for Congress. I didn’t want to work for Martin Luther King Jr. I wanted to work close to him and be a writer and write about the movement.”

Young was born March 12, 1932, in New Orleans to college educated parents: a teacher and a dentist whose patients included Olympic medalist Ralph Metcalf and jazz great Louis Armstrong.

“I grew up middle class in that both of my parents had gone to college, but I grew up in a working class neighborhood. It was New Orleans and pretty mixed up,” Young remembers. “The Nazi party headquarters was 50 yards from where I was born, so I used to see Nazis walking down the street and you could hear then heiling Hitler. My father had to explain white supremacy to me early.”

Young was supposed to follow his father’s footsteps and be a dentist — or a baseball player. But shortly after he graduated from Howard University in 1951 with a biology degree he found himself in Marion, Ala., pastoring a small Congregational church.

There, Young married Jean Childs in 1954. They had four children. The namesake of Jean Childs Young Middle School died of cancer in 1994. He married his second wife, Carolyn McClain, in 1996.

Along the way, he turned the heads of countless other women. Noted author Tina McElroy Ansa recalls that as a student at Spelman in the early 1970s, one of her first journalism assignments was to interview Young about his first run for Congress. She said all the students at Spelman had crushes on the young Young, and she was so flustered that she forgot to turn on her tape recorder during the interview.

Young says that of all his many roles, sex symbol was the one he was least prepared for.

“That was one of the things that shocked me. I never thought of myself as good-looking,” he said, glancing at a poster of his younger self with a perfectly manicured afro. “Growing up in New Orleans, when looks were defined as [light] skin color and straight hair, I didn’t qualify.”

Young prefers to talk about the days of running the Citizenship Schools, where young people were trained to go into hostile communities and risk death to register black voters.

That prompts memories of the song, “This May Be the Last Time,” which was sung at meetings after “We Shall Overcome” — a reminder of the danger inherent in the organizers’ task.

Young’s eyes sparkle. At 80, he and Lewis, 72, and Joseph Lowery, 90, now truly represent the old guard.

“This may be the last time we ever see each other/I don’t know. This may be the last time we ever sing together; I don’t know,” Young sings. “This may be my last time we pray together; I don’t know.”

“We were living in the presence of death all the time. We either sang about it or joked about it. Every time we did something with Dr. King, he would pick out one of us to take a bullet for him, and then he started preaching your funeral. It was satire at its best,” said Young, who recovered from a bout with prostate cancer in 2000.

“But I never put a number on how long I thought I would live. I always lived like this might be the last time.”

RELATED: Andrew Young: Nothing you can’t solve without violence