As early voting is underway in Georgia’s first general election since the razor-thin 2020 presidential contest, law enforcement and election officials are watching for disruptions by radicalized individuals feeding off conspiracy theories and disproven allegations of fraud.

This year’s election could be at risk of threats, interference and misinformation that has been building over the last two years since the proliferation of stolen election claims by former President Donald Trump and his supporters has taken hold, experts say.

“We’re definitely concerned and prepared,” said Ben Popp, a researcher for the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism.

Popp tracks extremist groups in the Southeast and said there are reasons to think the period leading up to and immediately following the midterm election could be disruptive. How and where that disruption might occur is more difficult to predict, he said.

“It’s largely election fraud narratives,” he said. “We haven’t really seen specific threats toward specific election workers, but the generalized rhetoric is there.”

Popp said the largest source of concern does not come from extremist groups like the Proud Boys or Oath Keepers or fringe political ideologies like neo-Nazism. Instead, the growing concern has been individuals spurred to action by online far-right influencers warning a grand conspiracy is afoot by Democrats to steal the election, he said.

State and federal officials are preparing to respond to tactics aimed at election workers and voters. On Oct. 12, the FBI issued a warning that it would prioritize investigations into threats made against election workers. And Wednesday Ryan Buchanan, U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Georgia, appointed one of his assistants to spearhead the handling of complaints regarding the election.

“Every citizen must be able to vote without interference or discrimination and to have that vote counted in a fair and free election,” Buchanan said. “Similarly, election officials and staff must be able to serve without being subject to unlawful threats of violence.

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger’s office issued guidance this month to county election officials clarifying that a voter’s eligibility cannot be challenged at the polls and must be in writing. Only then can county election officials review the challenge and determine if probable cause exists to investigate further, the bulletin states.

Raffensperger’s office also set up a text message line for poll workers to report problems by sending a five-digit number that relays information to county and state election officials working closely with law enforcement to respond.

“We want to ensure that we keep polling places safe, and I think this shows our concern. We’re placing a premium on election security,” Raffensperger said. “We want to protect our election workers because they’re the true heroes of democracy.”

Local election officials have already seen the impact disinformation is having.

“We have gotten a lot of folks showing up to make public comments and peppering us with emails. A lot of it is rooted in conspiracy theories, so that does concern me,” said Dele Lowman Smith, chairwoman for the DeKalb County elections board. “As it persists, it starts to get a hold and people begin accepting it as truth.”

‘A hostile attitude’

This month, former Trump adviser Steve Bannon, who spearheaded the “Stop the Steal” movement after the 2020 presidential election, issued a call to the listeners of his internet talk show to volunteer as poll workers and poll watchers during the midterms. In an interview on Bannon’s show, Trump attorney Cleta Mitchell named DeKalb County as a location where volunteers were needed.

“This is about settling this,” Bannon said, suggesting, without evidence, that votes might be cast by noncitizens and that other democratic safeguards were not in place. He urged challenges to residency and signature verification on individual ballots.

“We want Republicans to have steely resolve when they get in the room, to not back down,” he said.

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

While volunteering to be a poll watcher is a traditional civic activity for Republicans and Democrats alike, Madeline Peltz of the left-wing watchdog group Media Matters for America said the context of the callout matters. Bannon has continued circulating conspiracy theories about the last election in the runup to the midterms, she said.

The call to members of his audience to volunteer represents “a sort of hostile attitude towards voting, rather than one that is meant to sort of facilitate the smooth process of democracy,” Peltz said.

Some of the anxiety around the election has been fueled by the debunked documentary “2000 Mules,” which claimed a virtual army of people fraudulently stuffed ballot drop boxes with fake presidential ballots in Georgia and elsewhere. Despite widespread criticism of its methods and conclusions, “2000 Mules” and the rhetoric behind the “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was fraudulent is having an impact on the election process.

In July, a group of conservative voters in Gwinnett County, backed by an organization that claims the 2020 election was stolen, challenged the eligibility of 22,000 registered voters based on their own research using tax and property records — a process allowed under the new state election law. Earlier this month, the Gwinnett County Board of Elections dismissed the challenges by a 3-2 vote due to a lack of any hard evidence that the voters were not county residents.

Popp and other extremism researchers have been monitoring fringe channels on Telegram and conspiracy sites where election-based conspiracy theories are often accompanied by threats of violence. It’s not hard to find.

“We’ll be seeing vigilante justice one way or another before too long. At some point good people lose patience with unpunished lawlessness,” one user on Patriots.win, a pro-Trump internet message board that traffics in conspiracy theories, posted in a thread about theft of political signs.

Meanwhile, foreign governments are trying to amplify these partisan grievances to further sow discord and disrupt the American political landscape, according to researchers. Marek Posard, a disinformation expert at the RAND Corp. think tank in Washington, D.C., said state actors in Russia, China and Iran are looking to promote a scenario where people question the midterm results by creating fake social media accounts and posting hyperpartisan memes they hope will go viral.

“We have gotten a lot of folks showing up to make public comments and peppering us with emails. A lot of it is rooted in conspiracy theories, so that does concern me."

Posard said these so-called “troll farms” are cheap to run and can cause real disruption. Such efforts target both the political left and the right as the trolls seek to exploit existing divisions, he said.

“The ultimate goal is to make it seem like our system of government doesn’t work,” he said.

Special police training

Risks to election officials and workers peaked after Election Day in 2020, when Trump supporters targeted government officials from Raffensperger to Shaye Moss, a Fulton County employee working in State Farm Arena on election night who received death threats based on false accusations of fraud.

The harassment grew so severe that Gabriel Sterling in the secretary of state’s office publicly called on Trump to reject violence.

“Someone’s going to get hurt. Someone’s going to get shot. Someone’s going to get killed,” he said.

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

A month later, Trump supporters rioted at the U.S. Capitol and delayed Congress from accepting the results of the election.

“I hope it doesn’t happen, but if people are shooting up schools, I feel like it’s going to happen sooner or later” during an election, said Richard Barron, who was Fulton County’s elections director in 2020. “There’s so much anger out there. It just seems to be boiling under the surface. We’re just trying to do our jobs.”

DeKalb Elections Director Keisha Smith has heard the “chatter” but she said the number of volunteer poll workers this year is consistent with past elections.

“Through our mandatory training, all of our poll workers know that any efforts to deliberately undermine or interfere with an election is a crime and will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law,” she said.

Sheriffs across the state have been briefed on how to watch out for potential dangers, said Chris Harvey, the state’s former elections director who now trains police as deputy executive director for the Georgia Peace Officer Standards and Training Council.

Police are familiarizing themselves with the names and addresses of polling places and election warehouses so they can quickly respond if they receive a call at that location, Harvey said.

“We’re seeing the rise of people that are going to be self-appointed poll watchers who are intent on finding all the flaws that they believe exist in what they think is a broken system,” Harvey said. “They may be marginally informed but zealous in their beliefs.”

Disrupting a polling place could be a crime under Georgia law, Harvey said. Police in several states are being provided with cards they can carry in their pockets that summarize election laws, which in some cases aren’t covered during regular law enforcement training.

“There's so much anger out there. It just seems to be boiling under the surface. We're just trying to do our jobs."

The most significant risks to elections could come after Election Day, as they did in 2020, said Matthew Weil, director of the Elections Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

He’s most concerned about the danger of county election boards refusing to certify results, and local election officials granting unauthorized access to ballots and vote-counting equipment, as they did in Coffee County in South Georgia in early 2021. The Coffee County case is under investigation by the GBI.

“There’s no simple policy solution,” Weil said. “We’ve now been buffeted by six years of relatively consistent and directed misinformation campaigns. We want everyone to participate, but don’t go in with this completely skeptical perception and act on it.”

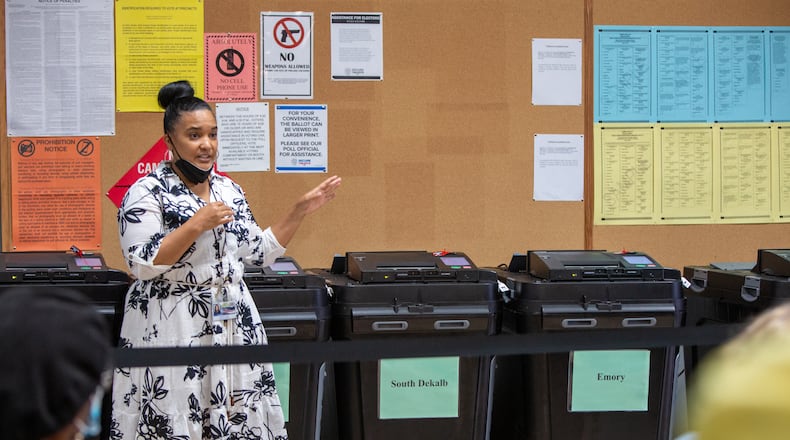

Credit: Alyssa Pointer/Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Credit: Alyssa Pointer/Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Bishop Reginald Jackson, who leads 500 African Methodist Episcopal churches in Georgia, said he’s worried about aggressive poll watchers and lawyers who could attempt to intimidate voters or election workers, especially in heavily Democratic areas in metro Atlanta.

“I think they intend to try to instill fear,” Jackson said. “I don’t doubt that there’s going to be some people who show up as if they have some authority to monitor these polls.”

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured