Norma Patton knows the pain killing can bring.

In the 1970s, she helped her husband Carl Patton plan a series of deaths that became known as the Flint River murders. Shortly after Carl’s 2003 arrest she admitted her part in the killings and testified against her husband, sending him to prison for multiple life sentences.

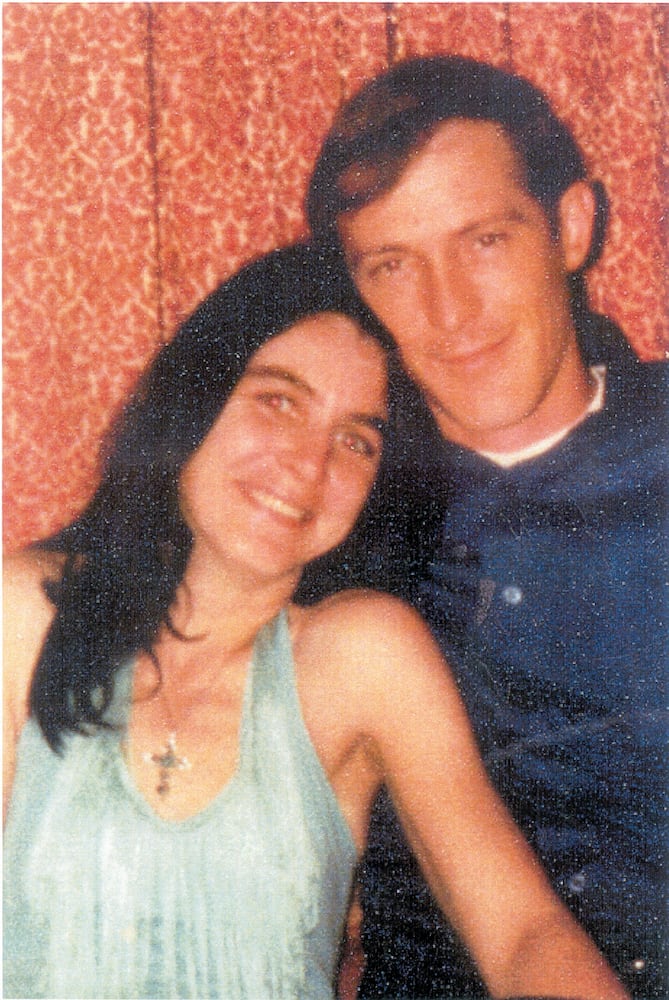

She learned more of pain killing brings in 1998, when her daughter, Melissa Wolfenbarger, a 21-year-old married mother-of-two, disappeared. On August 6, 2024, Atlanta police arrested Christopher Wolfenbarger in the death of his wife. He remains in the Fulton County jail, awaiting an arraignment hearing.

Norma Patton waited 26 years to tell police the truth about her husband. She waited 25 years for police to arrest her son-in-law.

Credit: WSBTV Videos

DNA testing created the breaks investigators needed in both cases.

“In April (of 1999), a severed head was found in a wooded area near (Melissa’s) home in southwest Atlanta, and more severed remains were found nearby in June,” the AJC’s Rosana Hughes and Lexi Baker reported in the Aug. 7 Journal-Constitution. The remains were initially misidentified as male. In 2003, the Fulton County Medical Examiner’s Office confirmed them to be Melissa’s.

The remains were originally thought to be those of Larry Lund, a Macon painter murdered in 1999. Lund was also decapitated, his body dumped along the Ocmulgee River near the Twiggs-Houston County line in middle Georgia.

Norma Patton knew about bodies being left in rivers, too.

The Flint River murders

The Flint River murders, so called because two of Carl Patton’s victims were discovered in that river at the Fayette/Clayton County border, were an intricate mix of romantic rivalries, revenge and, ultimately, the revelation that one murder sparked another. Then another. And then two more.

The crimes took place in multiple jurisdictions, creating a tangled web of investigations and prosecutions in multiple metro Atlanta counties.

Atlanta Journal reporter Dale Russakoff detailed what he termed the “murder trail” in an Oct. 25, 1978, feature in the newspaper’s Metro section.

“In early 1973, (Carl Patton’s uncle) Fred Wyatt moved to Atlanta to live with Marie and Richard Russell Jackson,” Russakoff wrote “That March, Jackson’s body, riddled by five bullets, was found beside Fairview Road in Henry County. He had been dumped there late at night, according to a police report.

“Soon afterward,” Russakoff continued, “Wyatt and Marie Jackson began living together as a common-law couple. Mrs. Jackson took Wyatt’s name, and lived with him for almost five years.”

The relationship ended in summer 1977, when Wyatt left Marie and rented a home in Clayton County with Betty Jo Ephlin. In October of that year, Ephlin became Carl Patton’s second victim, allegedly the victim of a murder-for-hire revenge scheme set up by Marie Jackson Wyatt. She was suspected of involvement in all of the murders.

Credit: AJC Archives

Credit: AJC Archives

When Fred Wyatt returned from a trucking trip, Ephlin was gone. The third killing happened soon after her disappearance. Wyatt was found dead in his smashed car Nov. 12, “the victim of an apparent car-train collision” up the road from the Clayton home he’d shared with Ephlin.

“Months later,” Russakoff reported, “police executed search warrants and recovered Mrs. Ephlin’s possessions in three places — Marie Wyatt’s trailer, the Pattons’ house and the Jonesboro apartment shared by an unmarried couple, Joseph Cleveland and Liddie Matthews Evans.”

Cleveland, a firefighter in the now-defunct town of Mountain View, was Patton’s childhood friend. He and Evans also disappeared, becoming Patton’s final two murder victims.

“On Dec. 17, the Pattons were supposed to take Cleveland and Evans on a trip, Evans’ children told investigators,” Russakoff reported. “Police say the Pattons were the last to see (the couple) alive.”

Marie Wyatt’s attorney, Clarence Leathers of Jonesboro, saw things differently, telling the Journal that the Pattons were “the last people other than the murderers.”

Decades later, Norma Patton would testify that they were, in fact, one and the same.

An arrest, a deal, a trial, a confession

AJC reporter Ralph Ellis covered Carl Patton’s March 7, 2003, trial in Clayton County Superior Court, breaking down Norma Patton’s testimony about the 1977 murders as follows:

“(Carl) killed Wyatt and Ephlin in Clayton County with help from Cleveland (in November). Ephlin was shot and tossed in the Flint River. Wyatt was shot and put into a car that was pushed into the path of a train to make the death look like an accident,” Ellis reported. “(Carl) worried that Cleveland would talk, so the Pattons decided to kill Cleveland and his girlfriend, Evans, in December. Those killings occurred in the Pattons’ living room in south DeKalb.”

Evans’ body was found in the Flint River near Ephlin’s in December 1977. Cleveland’s was found in the Ocmulgee River in Butts County in April 1978.

The Pattons were jailed in Fayette County Dec. 22, 1977, but released in early January 1978. They were arrested again in 2003 after GBI crime lab technicians matched a blood-stained pillow to Evans’ DNA. Norma Patton agreed to testify against her husband to face reduced charges.

Carl Patton confessed to Richard Russell Jackson’s 1973 slaying after being found guilty of the four 1977 murders. Patton, a roofer from Locust Grove, is now serving five life sentences plus 20 years for the five killings. The Georgia Department of Corrections website says Patton is being held at Coastal State Prison near Savannah.

Marie Jackson Wyatt died in 1988, 15 years before Patton’s arrest, and was never charged with a crime.

Credit: AJC staff

Credit: AJC staff

Norma Patton’s cooperation wasn’t overlooked by authorities.

“(She) was sentenced to 12 months probation and fined $1,000 April 3 in Fayette County Superior Court,” Ellis wrote on April 10, 2003. “Norma Patton admitted she helped plan murders and hide bodies 25 years ago but was allowed to plead guilty to concealing the death of another, a misdemeanor.”

“She was given immunity from murder prosecution in exchange for testimony against her husband,” Ellis reported, “and that helped nail the case against him.”

“It’s my opinion that she saved the taxpayers a lot of money,” Fayette County Sheriff’s Department Investigator Bruce Jordan stated at the time.

Credit: AJC staff

Credit: AJC staff

Hunting a new killer

The Pattons, who are still married, have been seeking the truth about their daughter’s disappearance and death for two decades. When Carl Patton learned that his daughter’s remains had been identified and were in the Fulton County morgue, he “broke down and cried,” the AJC reported March 19, 2003.

The focus then turned to finding their daughter’s killer.

Enter Atlanta crime scene analyst Sheryl McCollum, founder and director of the Cold Case Investigative Research Institute, asked by the family in 2017 to help solve the nearly 20-year mystery. Melissa Wolfenbarger’s case led off McCollum’s Zone 7 podcast in February 2023 and the Patton family credits it with reigniting interest in Melissa’s case and the arrest of her husband.

At the August 7 press conference announcing Christopher Wolfenbarger’s arrest, Norma Patton offered praise for investigators as she took the podium and detailed what she claimed was a violent relationship between her daughter and son-in-law.

“We have finally made it,” the 73-year-old said, her voice shaking. “He’s in custody, and now we just need to get over the last hurdle and get him convicted.”

As Atlanta police outlined how the arrest finally came about, Norma and the Pattons’ surviving daughter, Tina, “wore shirts that (Norma) made when her daughter disappeared, each featuring a photo of Melissa,” the AJC reported.

“Tina Patton’s shirt read: ‘Justice has no expiration date.’”

ABOUT DEJA NEWS

In this series, we scour the AJC archives for the most interesting news from days gone by, show you original articles and update the story. If you have a story you’d like researched and featured in AJC Deja News, send an email with as much information as you know.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured