Each year in February, when The Atlanta Journal-Constitution produces a monthlong series on Black history, I challenge myself by writing about something or someone I know nothing about.

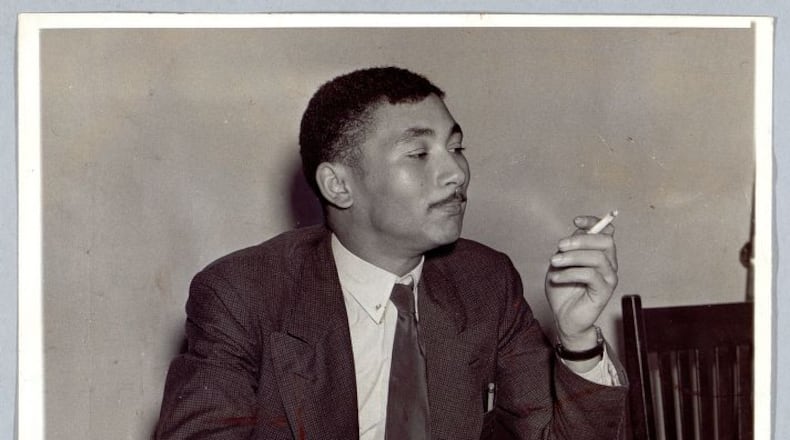

This year, I wrote about Angelo Herndon, who in the 1930s became one of the most famous Black men in the country during a five-year court battle that had a profound impact on American civil liberties.

Herndon, at age 19, arrived in Georgia as a labor organizer with the Communist Party. In 1932, he was arrested and charged under a state insurrection law for leading 1,000 Black and white workers in a march on the Fulton County courthouse, where they successfully and peacefully demanded financial assistance after the state had dropped 23,000 families from unemployment relief.

Herndon would bounce between state courts and the U.S. Supreme Court, engaging a who’s who of legal and political heavyweights, all in support of a case that would lay the groundwork for the protections of free speech and peaceful assembly that we enjoy today.

But for someone who had gained international fame, documentation of Herndon’s life and his work was difficult to find. A few weeks ago, when I received an email from a professor at Georgetown University, I learned I wasn’t the only one desperately seeking Herndon.

David Vladeck handles cases involving access to government records, and he is representing his colleague Brad Snyder, a legal historian, who is under contract to write a biography of Herndon.

Under the Freedom of Information Act, Snyder had requested all records relating to Herndon from the FBI and then from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in May 2022.

It took six months for NARA to search for the records, which include a total of almost 700 pages of FBI surveillance that spanned nearly 60 years of Herndon’s life.

The records include a treason investigation from 1934 to 1974, a domestic security investigation from 1946 and 1990, and a domestic security investigation in Washington, D.C., from April to July 1968.

Herndon was released from prison in 1937. He parted with the Communist Party in 1944. He got married and lived a relatively quiet life in Chicago before his 1997 death in Sweet Home, Arkansas.

Only during the last seven years of his life did the federal government decide he was no longer an enemy of the state.

“Why was Herndon subject to surveillance even after he backed away from activism and politics?” asked Vladeck in a letter to NARA.

It’s a good question, but as it stands, we won’t be able to read the answer in Snyder’s forthcoming book.

NARA has determined that it will take four years to process the documents on Herndon, long after Snyder’s book is due. Agency officials rejected Vladeck’s requests to expedite the records, on the grounds that there is no urgent need to inform the public of government activities and that the topic is not of widespread media interest.

We are living in a moment when it feels as if our civil liberties are under attack. It is a moment when an actual insurrection has occurred. But the agency charged with preserving important records and materials involving the federal government does not believe the release of documents associated with a case that set the standard for these concerns should be considered urgent.

Would we not gain some insight into the present by understanding more about Herndon’s history?

In 2018, Rebecca Wu, a spokeswoman for the FBI in St. Louis, told the Intercept that the FBI does not engage in surveillance of individuals who are exercising their First Amendment rights but the FBI does review intelligence that indicates an individual might be involved in criminal activity or pose a threat to national security.

How does Herndon’s 58 years of FBI surveillance compare to the Black Lives Matter activists who were also under FBI surveillance in recent years or the Jan. 6 insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol and may or may not be under surveillance?

“This is a story about our democracy. Can we protest what is happening with our state and country and not be thrown in prison?” said Snyder when we talked by phone. The records “would give us a fuller picture of Herndon’s life and why the FBI still considered him a domestic security threat.”

Snyder said he was drawn to Herndon’s story in part because it represents an important moment in time when the Supreme Court was focused on protecting our civil liberties.

“I am writing for people who want to know how we received basic protections of free speech and how we protected the right to peacefully protest. Herndon’s case is an important building block to protect that constitutional right,” he said.

Herndon’s story is a long-forgotten piece of American history that deserves to be told in its entirety.

There is no better time than the present to tell it.

Read more on the Real Life blog (www.ajc.com/opinion/real-life-blog/) and find Nedra on Facebook (www.facebook.com/AJCRealLifeColumn) and Twitter (@nrhoneajc) or email her at nedra.rhone@ajc.com.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured