A long-awaited honor for Atlanta civil rights activist

Gundi Mants Turner felt like she might be floating on a “pink bubble” as a crowd gathered recently to honor her late uncle Robert Mants Jr.

For most of her life, she either witnessed or heard stories of his contributions to the civil rights movement. And while others like the late Congressman John Lewis and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. have long been celebrated for their civil rights work, Mants remained in the shadows for much of his life.

Outside of his family and close friends, few were familiar with the work he did, starting with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

“He was never the type to want to be upfront and recognized, but he was upfront,” Turner said recently. “He was right there when they knocked John Lewis to the ground and water hosed him.”

Indeed, Mants suffered the same humiliation as other leaders of the famed march.

So when a 22-mile stretch of U.S. 80 was renamed Robert “Bob” Mants Memorial Freeway, Turner said she could barely contain her excitement.

She was among nearly 250, including a host of relatives and friends, who gathered April 25 at a dedication ceremony in Montgomery, where Mants spent most of his life.

Alabama Reps. Kelvin Lawrence and Prince Chestnut spearheaded efforts to rename the freeway.

Prince said that he began the work last year because Mants was a noble man.

“He helped people. And unlike other leaders, he did not seek the spotlight,” Prince wrote in an email exchange. “Instead, he did the work.”

Prince recalled that when he was a young lawyer representing Lowndes County, Mants would often attend meetings to offer words of encouragement to him. It would be much later that he understood Mants’ place in history.

“Most people with his resume broadcast their feats, but he did not,” Prince wrote. “Moreover, he actually moved from Atlanta to Lowndes County, Alabama, remained here, and continued to work long after Bloody Sunday. It was the reverse of what most people do, which is move from rural Alabama to metropolitan areas.”

Prince said that people like Mants, who work for others and do not seek the spotlight, are often overlooked.

“His work with voting rights, participation, and organization affords me the opportunity to hold my office of public trust,” Prince wrote. “Lowndes County and Central Alabama today are vastly and politically different from the one he inherited when he first moved here in the late 1960s. Much of the positive change is a direct result of his work. His commitment to humanity and his decision to live a normal life and raise his family in rural Alabama were important. He did not abandon this area as others have.”

Prince hopes that highlighting someone like Mants, who made Alabama his home, will “spur interest from other men and women of honor who will invest there or leave the big city and make this region home so that we can improve the quality of life for people who reside here.”

Mants’ daughter Kadejah Mants Broughton, also of Atlanta, called her father her first love but said he wore many hats.

She said he was an “ordinary man who walked this earth with purpose and wisdom and shared it with everyone.

“I am grateful and honored to be able to let the world know he was here and what a difference he made.”

The Alabama Legislature voted to rename a 22-mile stretch in 2021 but did not appropriate funds for signage. Mants’ family recently raised enough money to make that happen.

At the height of the civil rights movement, Mants moved from his hometown of Atlanta to Lowndes County, Alabama, where he helped plan the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965.

By then, he was already in the thick of the movement, volunteering at the SNCC headquarters.

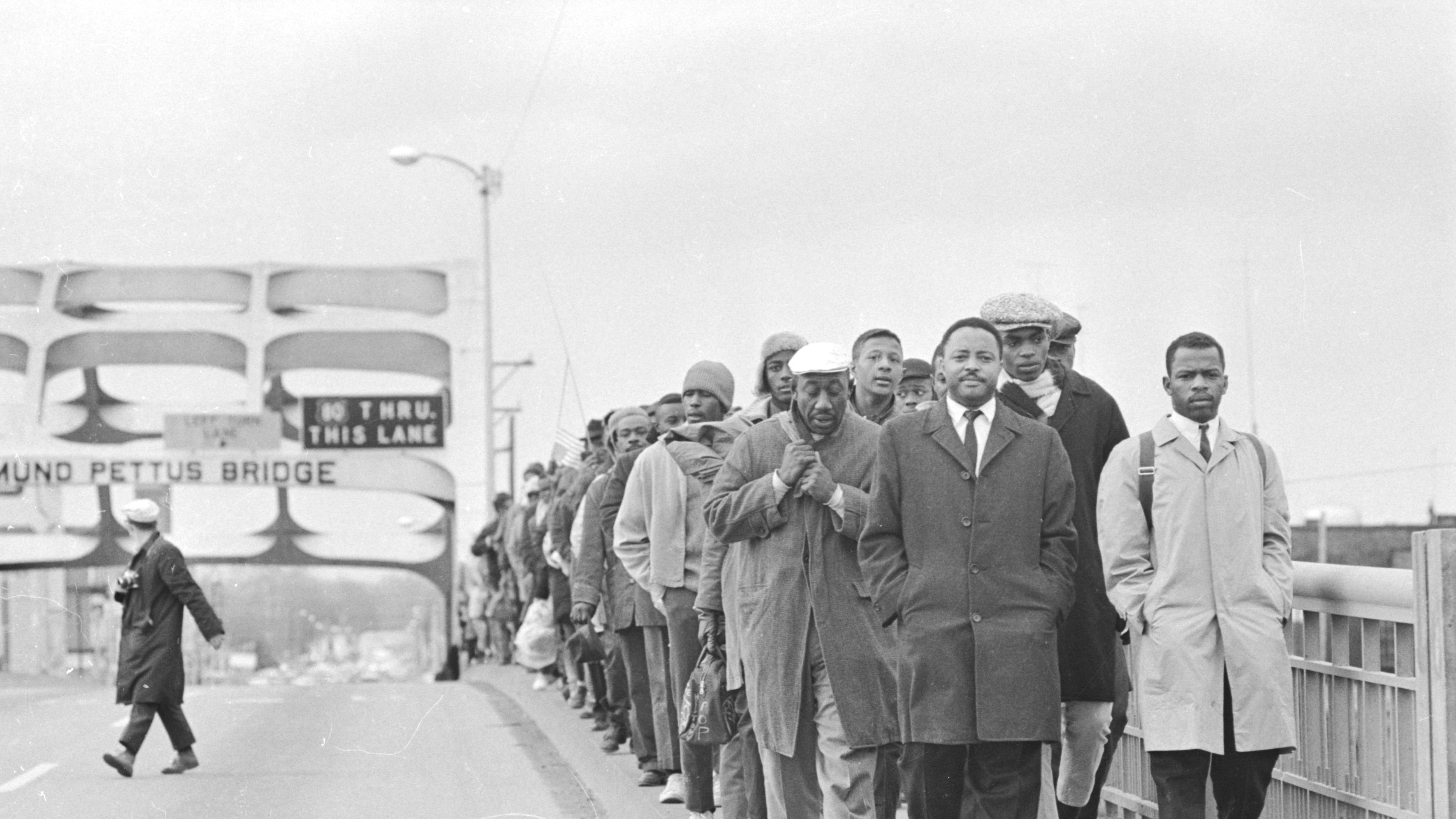

Photos captured him standing immediately behind Lewis on Bloody Sunday when the late congressman led the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

Mants would remain in Lowndes County where he helped register Black people to vote and then create a temporary tent city for those who’d been evicted from their homes in retaliation for registering.

He would go on to serve as a Lowndes County commissioner for many years. He passed in 2011 after suffering a heart attack during a visit to Atlanta.