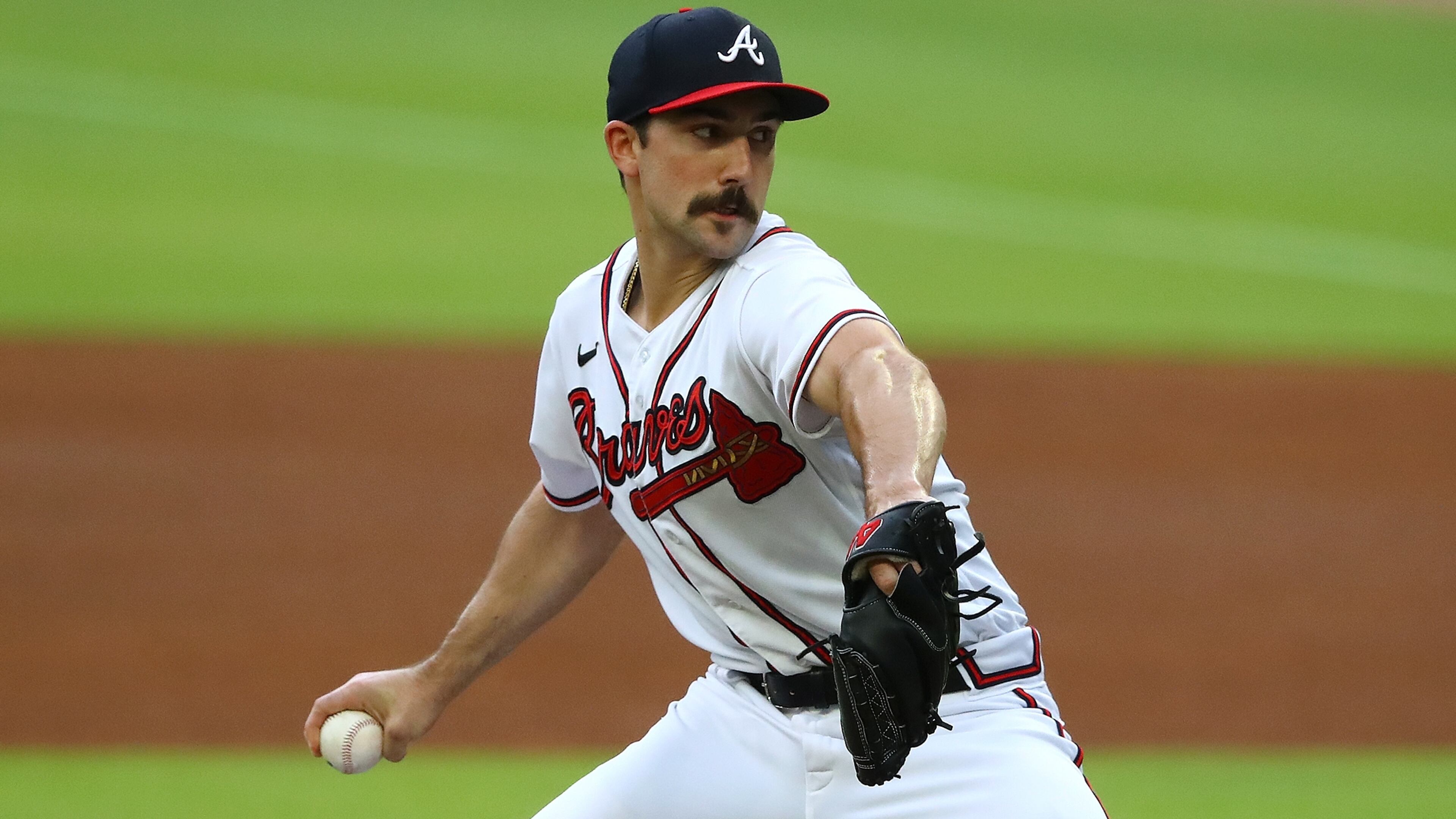

Before and after: How Braves’ Spencer Strider evolved after Tommy John surgery

To Spencer Strider, there are two parts of his baseball life: “PTJ” and “ATJ.”

Pre-Tommy John and After Tommy John.

From pursuing his hobbies to rebuilding his arm action and more, the 23-year-old Strider puts purpose into everything. Ask him why he does something and chances are he will say he began doing it after undergoing Tommy John surgery in 2019.

Recently, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution talked to Strider about the ways Tommy John changed him – on and off the field.

Following his impulse

Before Tommy John surgery, Strider felt he had to allocate so much of his time to baseball and school. If he engaged in another activity, it would be taking away from baseball or academics.

He’s different now.

“A lot of it was not being so hesitant to sort of follow my impulse,” Strider said.

If he wanted to read a book, he would read a book. And he had always wanted to kayak, so he finally picked up that hobby while rehabbing from his procedure because he figured there was no right time to do that or anything.

“Sort of just that realization that if anything is going to happen – whether it’s something as innocuous as me wanting to go to a coffee shop – I have to just make the decision to do that,” Strider said. “That’s part of the whole purposeful responsibility that came from rehabbing TJ. The only thing that’s going to make me better is me doing it actively.”

In professional baseball, Strider said, “a lot of our time isn’t ours.” Thus, players must make the most of the time they have to themselves.

Nowadays, Strider enjoys reading, which he understands may be more appealing as he’s gotten older. He’ll also explore cities on the Braves’ road trips. He does what he wants to do at a particular time.

“I kick myself because I didn’t go walk around the city, go to a coffee shop and do something cool, and other days I do and then it kind of wears me out,” he said. “It’s just my impulse. Whenever I feel like doing something, I just do it. That’s kind of the happy balance.”

Putting purpose into everything

During his rehab, Strider worked with Cory Shaffer, Clemson’s sport psychologist. They discussed everything, from doing things with purpose to building a routine. Many times this season, Strider has brought up working with Shaffer.

You can tell it was a formative time for him.

One main lesson Strider took from his rehab: the concept of purpose. Baseball is a sport that includes many routines and superstitions. But why are they performed?

Shaffer and Monte Lee, Clemson’s former head baseball coach, always talked about the “why” in everything. They always urged players to ask why something was done. They wanted them to truly understand the meaning behind everything, even things as simple as stretches or drills.

“Having a defined goal for a stretch or any activity makes it that much more effective,” Strider said. “I think that takes into just your daily life. Why am I doing this? It adds more value to it.”

‘Well, how do I not get hurt again?’

Before Strider needed Tommy John surgery to repair his ulnar collateral ligament, he had always thought – and had been told – he had good mechanics. He took care of himself. He utilized the information he had at his disposal.

“Within what I understood about baseball,” he said, “I was doing a good job.”

But he now realizes some of that information was incorrect or outdated. So when he got hurt, his mind went to one thought:

“Well, how do I not get hurt again?”

He worked on identifying aspects of his delivery, throwing program, routine and everything else that could have made him more prone to injury.

One change he felt necessary: a shorter arm action. So Strider – listed at 6-foot and 195 pounds – looked at shorter pitchers with similar builds. He studied Trevor Bauer, who is listed at 6-1 and 205 pounds – and is an explosive pitcher.

“The only way I was going to get that what I wanted was to focus on each day and doing the little (things)."

“You’re going to look to people who are where you want to be and better than you, but are also attainable,” Strider said. “For me to try to be Jacob deGrom at that point didn’t make any sense. I’m not 6-foot-4, I’m not long and lanky, I wasn’t throwing 100. Low 90s and shorter arm action, that made sense to copy (Bauer).”

Strider then took a long road to shorten up his arm. “It was a lot of trial and error,” Strider said. He knew where he wanted to go but had to figure out the steps to get there. Something that helped: He had a detailed outline and idea of what he wanted to accomplish, which helped steer him in the right direction even if he didn’t have a perfect method to end up at the destination.

Strider learned that to shorten his arm, he needed to focus on other parts of his body.

“When you rehab TJ and you start throwing, your first throws are the bare minimum effort,” he said. “You’re hardly throwing, really. It’s like that for most of it. So you’re able to sort of manipulate your body and put it in positions you want to go because you’re moving so slow. So it’s hard to gauge if you’re actually picking up some of these new movement patterns.

“And then you start putting some on it and you realize that your body is trying to revert back to what it knows, because that’s all it’s ever done. I was so focused on my back arm and trying to get it to shorten up and follow the path I wanted to go through, and then I realized I need to think more about my front side, more about that part of my body, and it will put my arm where it needs to be. So once I realized that, it started to happen pretty fast.”

How Spencer Strider began hitting triple digits

Ah, we’ve finally reached the quality for which Strider is known: his velocity.

Strider, whose fastball averages 98 mph, regularly hits triple digits. He has hit 101.7 mph this season.

But how did he get here after sitting 94-96 mph, and hitting 97, when the Braves drafted him in 2020?

It proved to be a multi-step process. The shorter arm action led to added velocity because, as Strider put it, it was “just more efficient movement and allows the power to be applied a little bit more efficiently and effectively.”

And during the COVID-19 layoff, Strider focused on strengthening his lower body. At that point, he worked himself harder because he had overcome the anxiety that came with his injury. He was no longer wondering if he would get hurt again.

His velocity, which was a tick up when he returned after Tommy John surgery, has steadily increased since.

‘Dry reps’

Most kids watch highlight videos on YouTube. Strider watched routine videos.

He wanted to know how Max Scherzer or Clayton Kershaw prepared for a start, and he wanted to see it with his own eyes. He also watched videos of Marcus Stroman.

He took the idea of “dry reps” from Kershaw. He’ll do them the day before he makes a start.

“As a starter, I like to go down to the bullpen and just take a breath, get on the rubber just like it’s a game, and just go through some pitches,” Strider said. “Just pretend that I’m locking right into that in-game routine. And then the next day, it sort of falls into place.

“I think there’s a lot to be said for walking your mind through things and prepping it that way. The body tends to follow.”

The dry reps are only one way Strider delves into the game’s mental side. He also keeps a journal, which he believes is “sort of matching the subjective and objective thoughts.”

‘Adversity is great’

When Strider was younger, he received a common message from those wiser than him. He then heard it again when he worked with Shaffer at Clemson.

“Adversity is great,” Strider said.

He soon added: “You need failure.”

Failure, he said, highlights areas for improvement. “You can only get so good just hammering what you’re good at,” Strider added. One must bring up what is lacking.

When Strider evaluated himself during the rehab process, he thought a lot about where his confidence came from as he chased his goals. He had always wanted to be a big leaguer, but high schoolers don’t see the specific steps necessary to achieve that goal. The bigs feel close, Strider said, but really are not.

“When you get hurt and you’re 21 years old and it’s your draft year, there’s a real realization that, man, this is it, this is a pivotal moment,” Strider said. “When that happens, you can either sort of lie to yourself and think that everything’s going to be all right, and just kind of hope and cross your fingers and leave it in other people’s hands, or you can really buckle down and be honest with yourself and say, ‘Here’s what I need to do, here’s where I’m not good.’”

Strider has learned his confidence comes from preparation. With the COVID stoppage and his first full offseason after last year, he had more time than ever to improve. He trusted himself and remained committed.

In a way, Tommy John surgery motivated Strider.

“I had to balance that sort of anxiety of ‘Man, I could really not be playing baseball again after a year here.’ Or it could be a great thing,” he said. “I think you have to leave it a little open-ended. In TJ rehab, I can’t make myself a draft pick, I can’t cause a team to draft me. I can’t become a big leaguer just by rehabbing TJ, so that’s out of my sphere of control.

“That may be the guiding perspective behind my day-to-day behavior and activity, but ultimately it’s just: What can I control? And that’s getting healthy, that’s maximizing my work every day, sticking to that process. And so eventually you trace the steps back to, OK, here’s my goal. Well, what do I need to do to do that? I need to play well. To do that, I need to be healthy. To do that, I need to have a good plan. To have a good plan, I have to execute day to day.”

Appreciating each day

Each day during his rehab, Strider couldn’t focus on the result because there were days when he couldn’t do much. Sometimes, his task was to do an exercise in which he pushed his elbow back into a wall. Other times, watching his college team’s game was the most intense thing he did that day.

“The only way I was going to get that what I wanted,” Strider said, “was to focus on each day and doing the little (things).”

As the days passed, Strider continued putting purpose into everything he did, no matter how small the activity.

Now he appreciates each day – and the little moments within it – much more.

“It definitely made me stay in the present moment, for sure,” Strider said.