Trial set for election security case against Georgia’s voting machines

A federal judge suggested a compromise in an election security lawsuit over Georgia’s voting equipment, but without an agreement, she ordered a trial scheduled to begin in January.

U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg wrote in an order Friday that the public might be better served outside of the court battle between Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and plaintiffs opposed to the state’s touchscreen voting system.

“Reasonable, timely discussion and compromise in this case, coupled with prompt, informed legislative action, might certainly make a difference that benefits the parties and the public,” Totenberg wrote in the 135-page ruling.

Totenberg said she won’t order Georgia to use hand-marked paper ballots, even if the plaintiffs prevail during the trial set to begin Jan. 9. She said it’s not within her power to mandate a new statewide voting system that would replace equipment manufactured by Dominion Voting Systems.

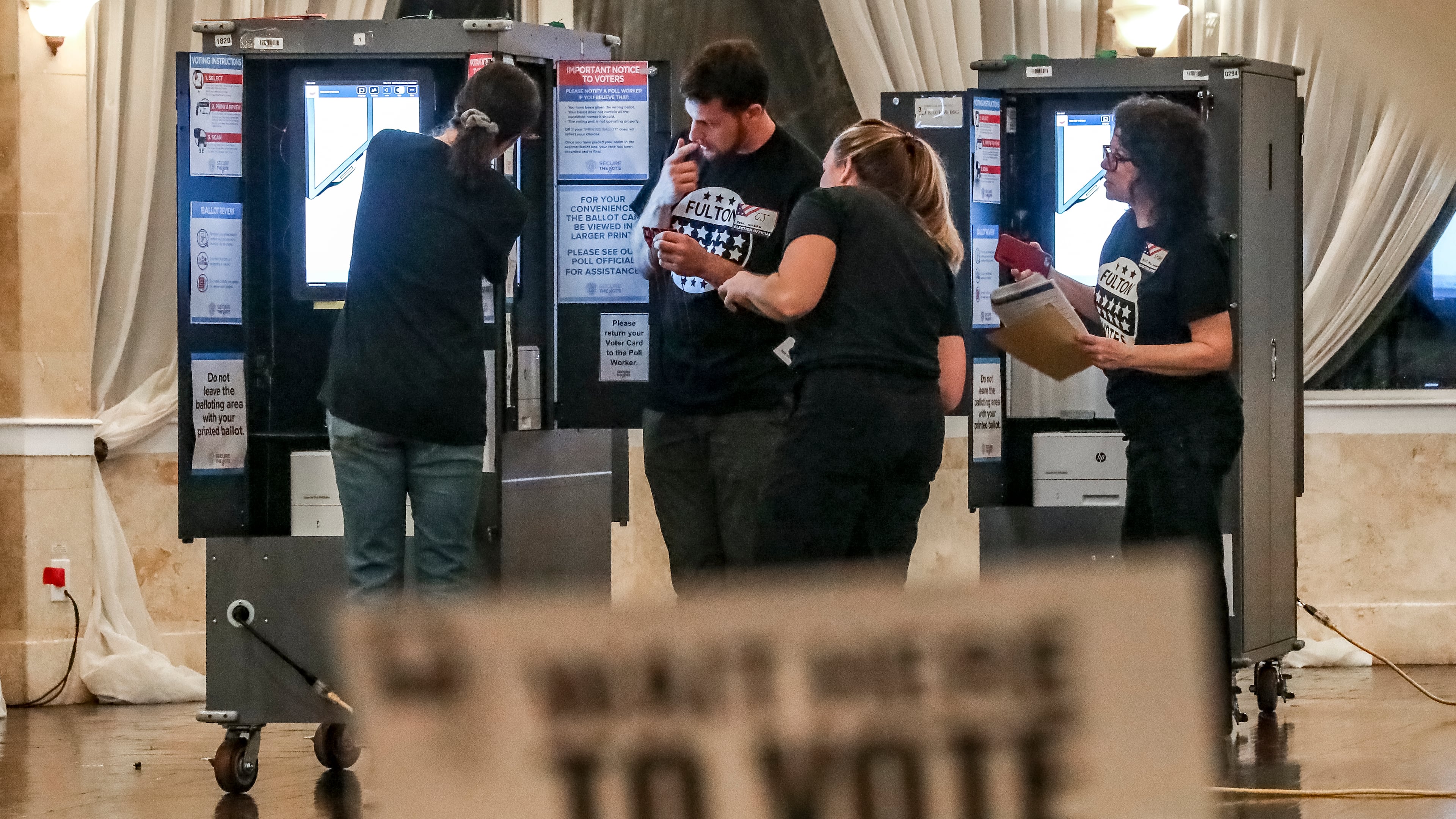

Georgia uses a voting system where voters fill out their ballots on touchscreens, which are attached to printers that create a paper ballot. The ballot displays voters’ choices in human-readable text alongside a QR code that is read and counted by scanning machines.

Critics of the technology say voters can’t be sure that the code accurately reflects their selections. Recounts and audits in Georgia have routinely confirmed the accuracy of vote counts.

Totenberg proposed eliminating the QR codes currently used to count paper ballots, holding more election audits and implementing cybersecurity measures.

“The court’s order makes it clear that Georgia’s status quo is far too risky, and that these concerning issues merit a trial,” said Marilyn Marks, executive director for the Coalition for Good Governance, a plaintiff in the case. “We look forward to prevailing at trial as we demonstrate why touchscreen BMDs (ballot-marking devices) cannot be used safely.”

Deputy Secretary of State Jordan Fuchs said the plaintiffs have never offered an election security solution that doesn’t include hand-marked paper ballots. The state has been fighting the lawsuit since 2017.

“We don’t negotiate with election deniers,” Fuchs said. “If they have an idea that wouldn’t take Georgia back to the days of hanging chads and stuffed ballot boxes, they should offer it.”

Through the lawsuit, the plaintiffs revealed evidence of an election breach in Coffee County in January 2021, when a nonprofit organization led by Sidney Powell, a lawyer who supported then-President Donald Trump’s claims that the 2020 election had been stolen, paid computer analysts to copy voting software, ballot images and other election data.

Powell, who was charged alongside Trump and 17 others in Fulton County with interfering in the 2020 election, pleaded guilty last month to six misdemeanor counts of conspiracy to commit intentional interference with performance of election duties.

“The facts marshaled by the court highlight a long story of incompetence, conflicting claims, and misinformation from the secretary about the Coffee County breach and its disturbing implications for easy access to virtually every component of the voting system,” said David Cross, an attorney for several Georgia voters who are plaintiffs in the case.

During the trial, Totenberg, who was appointed in 2011 by then-Democratic President Barack Obama, will consider whether Georgia’s touchscreen-and-paper voting system has major cybersecurity flaws that violate voters’ constitutional rights.

An expert for the plaintiffs, University of Michigan computer science professor Alex Halderman, identified vulnerabilities in the voting system’s software. He wrote a report that said votes could be altered by someone who gained access to voting equipment, such as a voter in a polling place or a corrupt election official.

The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency confirmed the vulnerabilities last year, but it found no evidence that weaknesses have ever been exploited in an election.

A Dominion-funded report by the MITRE National Election Security Lab, an organization that assessed Halderman’s findings, said hacks are “operationally infeasible” and easily defeated by routine election security procedures.

— The Associated Press contributed to this article.