Opinion/Solutions: Full beam ahead: Renewable energy grows

THE TAKEAWAY

China’s glowing solar power success shows there is light at the end of the tunnel for a global green energy transition.

Renewable energies such as solar are key to reducing emissions in the electricity sector, which is the single largest source of global CO2 emissions.

If the world is to reach net zero by 2050, almost 90 percent of electricity will need to come from renewable sources, with solar and wind likely accounting for most of that, according to the International Energy Agency, a Paris-based intergovernmental organization that works with countries around the world to shape energy policies for a secure and sustainable future.

Martin Green, a professor at Australia’s University of New South Wales who is considered an expert in solar energy, put it this way: “It seemed like science fiction a few years ago. But it’s all in place now and just needs scaling up and the will to do so.”

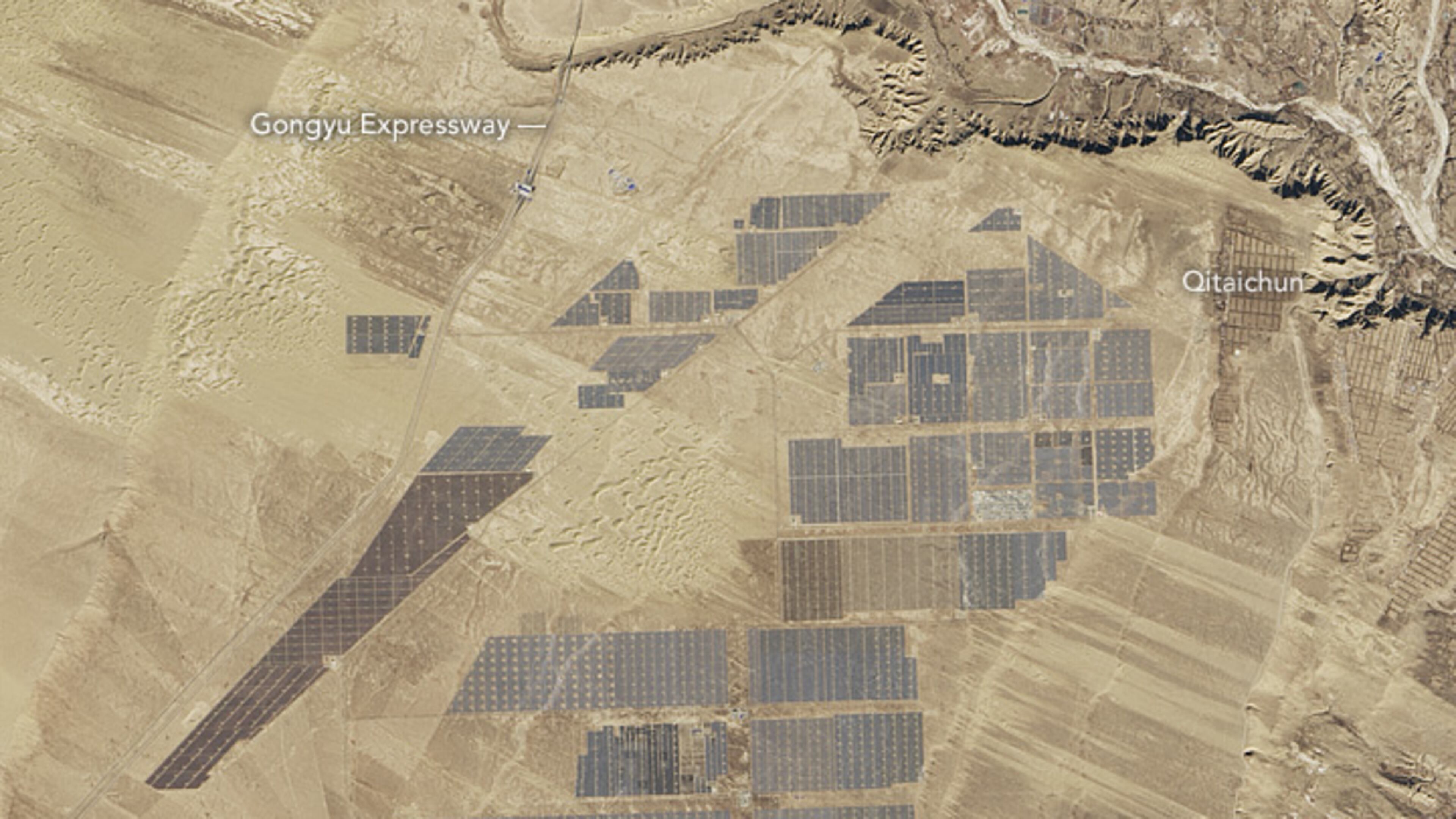

Atop the Tibetan plateau in northern China sits the Longyangxia Dam facility, a solar farm that is filled with a sea of four million deep blue-colored photovoltaic panels.

When construction was finally completed in 2017, it became the largest solar farm in the world, capable of producing 850 megawatts of power – enough to supply electricity for 200,000 households.

But now the Longyangxia Dam facility has been shunted out of the world’s top 10 largest solar farms. In fact, it’s not even in China’s top three.

“People don’t really comprehend the scale China is operating at,” said Tim Buckley, a global energy analyst and director of a think tank called Climate Energy Finance.

Today, China has the world’s largest renewable power capacity, including 323 gigawatts of solar, around a third of the entire global total.

President Xi Jinping wants to increase that to 1,200 gigawatts by 2030 – more than the world’s current total. The country is likely to reach that ambitious target years early.

The climate benefits of China’s solar revolution are clear:

As the world’s largest CO2 emitter, China’s has committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2060. Solar is a great way to do that. Within about four to eight months, solar panels have offset their manufacturing emissions and have an average lifespan of 25 to 30 years.

China’s rapid shift away from coal-burning will also help reduce air pollution in its smog-clogged cities, benefiting public health as well as the environment.

Huge infrastructure investment has also kept China’s economy ticking along at an impressive pace.

Last year, the country’s public and private investment in clean energy was $381 billion, according to the International Energy Agency, a Paris-based intergovernmental organization that works with countries around the world to shape energy policies for a secure and sustainable future. That’s greater than all of North America – by a margin of $146 billion.

The upshot of all this investment has been a downward impact on cost. As technology has improved and scale has increased, the cost of producing electricity with solar panels has plummeted dramatically: from $106 per watt in 1976 to $0.38 per watt in 2019.

“Relative to competition, solar has never been more affordable, even with inflation,” Buckley said. “And I expect costs to come down dramatically across this decade.”

U.S. looks to ramp up

Yet the geopolitical consequences of China’s domination of solar power have led to imbalances in solar supply chains.

Over the last decade, manufacturing has moved out of Europe, Japan and the United States. Today, China’s share in key manufacturing stages of solar panels exceeds 80 percent, presenting an “energy security” risk for many nations.

After years of falling further behind, the United States is now aiming to ramp up its role in the solar revolution.

In August, President Joe Biden signed into law the biggest climate bill ever passed in the United States, which includes $369 billion for clean energy.

It includes billions in subsidies for the clean tech manufacturing sector to compete with China as a key supplier of critical equipment for renewables, as well as grants and loans for auto companies to produce electric vehicles, $3 billion for the U.S. Postal Service to buy zero-emissions vehicles and $2 billion to accelerate research.

“There’s a technology race that the U.S. is losing,” said Buckley. “But as soon as the U.S. comes to the party, you know they will come at a million miles an hour.”

Constraints remain

Professor Martin Green, a professor at Australia’s University of New South Wales who is considered an expert in solar energy, argues that a more diversified industry, which is already beginning to emerge, will provide greater supply chain security and stability.

Europe has plans to take up solar much more quickly because of what is happening in Ukraine; India is quickly growing capacity; and Chile has ramped up installation.

“Now the whole world knows how to make solar cheaply,” Green said.

Some constraints, however, remain.

Solar requires significant upfront spending on capital. The sparsity of sunlight in cold regions like northern Europe is another issue, but even that is being addressed with the development of subsea cables, capable of transporting solar energy thousands of kilometers. And there are concerns about the impact of massive solar farms on ecosystems.

For now, it’s full beam ahead.

The International Energy Agency projects that solar will provide at least a third of global energy by 2050.

But that will require global production capacity to more than double by 2030, for existing production facilities to be modernized and the development of grids and storage.

The role of electric vehicles is likely to play a role in accelerating solar, too.

“I don’t see why,” Buckley said, “solar can’t get dramatically bigger than it is today.”

Peter Yeung writes for Reasons to be Cheerful, a nonprofit editorial project that strives to be a tonic for these tumultuous times.

About the Solutions Journalism Network language

This story is republished through our partners at the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about social issues.