Fifteen years ago, scientists from Georgia, Florida and Alabama played volleyball in order to build trust and let off steam after grueling days spent analyzing water-sharing scenarios involving the Chattahoochee, Flint and Apalachicola rivers.

One day the games stopped. Negotiations among their bosses to create a three-state commission, or “compact,” to regulate the flow of the waters from North Georgia to the Gulf of Mexico had broken down.

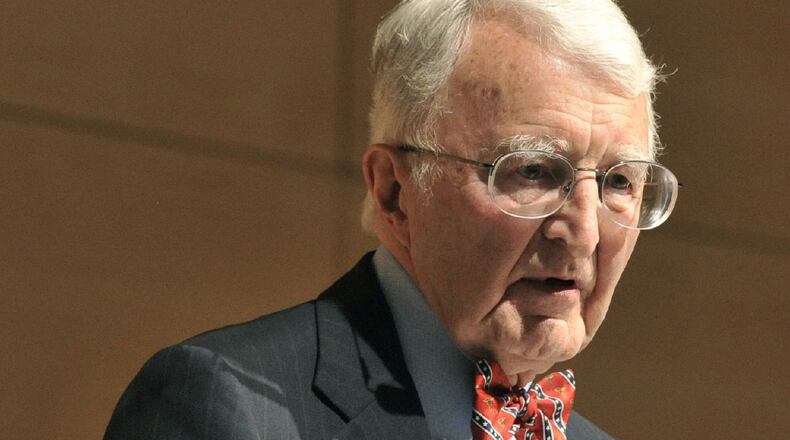

But the push for a tri-state compact never really died. And Ralph Lancaster Jr., appointed by the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve the latest water war legal battle, resurrected talk of a compact three times this week during trial. Once, he asked a witness whether an earlier attempt to create a regional water board was “a good thing”.

“We had great hope for it,” said Ted Hoehn, a Florida biologist and erstwhile volleyball player. “Staff tried to work together, but in the end it came down to (Georgia) saying, ‘This is the way it’s going to be.’ They would not come to an agreement.”

Years of lawsuits ensued, culminating in Florida v. Georgia, currently underway in this coastal New England town overseen by the curmudgeonly Lancaster, who was tapped by the high court to, possibly, end 27 years of litigation and ill will.

States across the country that share rivers employ congressionally sanctioned compacts to govern the flow of water between upstream and downstream users. The Supreme Court has repeatedly approved the “equitable apportionment” of interstate rivers, a water-sharing agreement at the heart of Florida v. Georgia.

Florida’s latest lawsuit, filed in 2013, accuses Georgia of hogging water from the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers to the economic and ecological detriment of the downstream Apalachicola River basin. Florida seeks a reliable amount of water from Georgia as well as a cap on metro Atlanta’s and/or southwest Georgia’s consumption of water.

The trial could last until Christmas. The Supreme Court, if it agrees to accept Lancaster’s ruling, could vote by late 2017. The stakes are enormous for metro Atlanta, which could see its water-fueled growth curtailed. South Georgia farmers could lose billions of dollars in crops without irrigation.

A compact in place these past 15 years would’ve salved tri-state acrimony and saved taxpayers tens of millions of dollars in legal fees. It would’ve governed the apportionment of an increasingly precious resource, particularly during the bad droughts of 2006-08 and 2011-12.

Lancaster’s questioning last week as the Supreme Court’s appointed special master buoys compromise-minded Southerners who’ve grown tired of the water wars.

“I am pleased that he brought it up,” said Wilton Rooks, executive vice president of the Lake Lanier Association, who has long pushed for a tri-state commission to manage the region’s water. “We need to start with some agreements and then build on them. A traditional compact would be a starting point.”

The blame game

Florida blamed Georgia for the compact’s demise; Georgia blamed Florida. It wasn’t always this bad.

In 1991, Georgia and Alabama, later joined by Florida, got the ball rolling on an Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) Compact. Deadlines for deals were repeatedly missed. Extensions were readily granted. Negotiations, though, weren’t the only game in town.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers controls the Chattahoochee River with five reservoirs and dams. Georgia asked the corps for more water from Lake Lanier in 2000 to slake Atlanta’s growing thirst. The feds declined.

Three years later the corps, Georgia and hydroelectric companies cut a deal that gave metro Atlanta a whole lot more water from Lanier. Alabama and Florida cried foul and accused Georgia of secret deals that violated "the spirit of the (compact) negotiations."

A compact compromise

The ACF Stakeholders, a grass-roots organization of scientists, utility managers, riverkeepers and others from Atlanta to Apalachicola, called for a Transboundary Water Management Institute to equitably manage water flows.

The institute would serve as something of a compact, requiring the three states and the corps to monitor river flows and aquifer levels daily to ensure enough water for Atlanta lawn-lovers and Apalachicola oysters. During droughts, it could order higher flows to save Florida’s mussels and sturgeon. During wet years, it could demand more water be stored in Lanier and other reservoirs as literal rainy-day funds.

“We have to think differently,” Sherk said. “We need to know what’s going on, both in quantity and quality, at all times in three river basins to make allocation decisions. There is so much uncertainty.”

And roadblocks. The stakeholder’s plan is on ice; water war negotiators didn’t want it interfering with their cases. Georgia, in particular, feels it has the upper hand legally. And Congress — not the judicial branch or any special master — under the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution regulates interstate water flows.

In addition, no final deal can be reached without the corps. Other federal agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency and the Fish and Wildlife Service, are intricately involved in water war issues, too. And Alabama, which is not a party to this lawsuit, could take up legal action in the future.

Compact or not, the water wars aren’t likely to end any time soon.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured