The unsafe and unsanitary conditions at Georgia's state prison hospital have caused one of its most experienced physicians to quit with a blistering letter that details the facility's problems and describes how he faced "smoldering and overt hostility" when he tried to correct them.

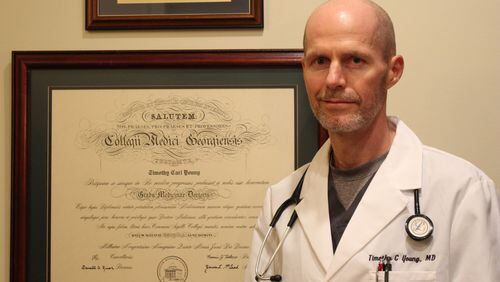

Dr. Timothy Young informed his supervisors at Georgia Correctional HealthCare of his decision to leave Augusta State Medical Prison at the end of this month in a letter that portrays the Grovetown facility and correctional medicine in the state as a whole in harsh and uncompromising terms.

Young, who has worked at the facility for 16 years, wrote that security lapses left him in fear for his safety. He also pointed to what he described as “extreme dysfunction” in the way healthcare is administered in the state prison system.

"I had hoped to continue my employment with GCHC until I reached retirement age, but the deteriorating conditions under which we have been left to work, especially over the past several months, have left me no option but to submit my resignation at this time," the 48-year-old physician wrote.

In an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Young added a new charge, saying he believes that the prison system has failed to hold doctors accountable when their negligence has caused inmate deaths.

"In my 16 years, I don't have enough fingers and toes to count the bad outcomes I've seen," he said. "And I've never seen one physician disciplined (as a result)."

Young’s departure and the circumstances surrounding it raise new and troubling concerns about Augusta State Medical Prison, the flagship of Georgia’s correctional medical system. The facility, both a closed security prison and a 55-bed hospital, has been under mounting scrutiny since the AJC exposed many of its problems last year.

The issues included leaking ceilings causing so-called black mold to grow in clinical areas, broken showers and toilets in the dormitories where inmates recovered from surgeries and security breaches that prompted nurses to quit on the spot.

As the medical director of the facility’s outpatient clinic, Young is walking away from one of the system’s most prominent positions, one that paid an annual salary of $191,000.

His claims have ramifications for both Georgia Correctional HealthCare, the branch of Augusta University that employs prison medical personnel, and the Department of Corrections, which is in charge of prison security and maintenance.

Randy Sauls, the Georgia Department of Corrections’ assistant commissioner for health services, declined to comment on Young or his letter. Instead, he cited a series of maintenance-related initiatives and said those, along with previously-announced leadership changes, should improve conditions.

After the AJC detailed problems at the prison, both of its senior administrators lost their jobs. The warden, Scott Wilkes, was reassigned to another facility. The hospital administrator, Randy Brown, was forced to retire after it was discovered that he secretly recorded his conversations with other corrections officials.

In a letter delivered to Young last week, Dr. Billy Nichols, Georgia Correctional HealthCare’s statewide medical director, wrote that the doctor’s concerns had “not gone unheard.” The letter listed several measures being implemented to improve security and maintenance but did not address Young’s claims of dysfunctional patient care or retaliation.

But Christen Engel, Augusta University’s associate vice president for news and communications, wrote in an email to the AJC that the university takes claims of retaliation seriously and has initiated an investigation into those raised by Young.

Some of the matters described in the previous AJC’s stories were based on information provided by Young. He declined to be quoted in those articles but agreed to be interviewed on the record for this story.

Describing his last year at the facility, Young cited a steadily growing frustration that first led him to raise concerns to prison officials, then to contact the media and, finally, a federal agency. When he subsequently faced what he perceived were acts of retaliation, he resigned.

Young said the issues at ASMP stem from “a catastrophic failure of management” at both Georgia Correctional HealthCare and the Department of Corrections that goes higher than Wilkes, who was moved out after only 18 months on the job.

“I would look to the people who put him there and fire them first,” he said. “I would look to the people who handed him the Titanic after it had already hit the iceberg, because that’s what he inherited.”

An exceptional record

Young began working at Augusta State Medical Prison in 2001, four years after his graduation from the Medical College of Georgia. He had been working as an emergency room physician in the Augusta area and was attracted to the job because it offered regular hours, he said.

After starting as a staff physician, he was elevated in 2004 to medical director of the outpatient clinic, a unit that provides specialty care for inmates throughout the state as well as urgent and routine care for those at ASMP.

The annual appraisals in his personnel file show his work was frequently rated as “exceptional,” the highest rating possible.

Young said he often found the job interesting and rewarding, but, as the years went on, he became increasingly alarmed by several aspects of it.

He said he became particularly concerned about patient care when he participated in mortality reviews for inmates who died at ASMP after being moved there from other prisons. The reviews frequently revealed that the inmates’ underlying conditions had been misdiagnosed or ignored, yet nothing was done to make sure the doctors responsible were disciplined or fired, he said.

Over time, he said, he came to the conclusion that the reviews were “pointless … just paperwork exercises to give administrators and managers a job.”

In 2015, the AJC revealed that nine female inmates had died under questionable circumstances while in the care of Dr. Yvon Nazaire, then the medical director at Pulaski State Prison. It wasn't until those stories appeared that a review by Dr. William Kanto, Augusta University's vice president for clinical outreach, determined that three of the deaths were due to substandard care.

Young also cited the case of a physician assistant he fired after the PA left a stroke victim waiting more than two hours in a hallway before receiving treatment. Although the matter was well documented, the PA, who is employed by a temporary agency, has since been allowed to work at another Georgia state prison, he said.

“How does that happen?” he asked. “Good question.”

Security was an issue, Young said, as often inmates were allowed to roam the facility without supervision or congregate in large groups.

“It’s just one of those things that’s incremental, and, the next thing you know, you have inmates milling around unsecured or 50 standing in the hall,” he said.

Young said he tried for months to alert Wilkes, Nichols and others to the problem without success.

In an email to the warden last February, Young recounted how earlier in the day he had gotten on an elevator with three unescorted inmates. He said he informed the inmates that they shouldn’t be on the elevator without a staff member and was told by one, “What are you going to do about it?”

`Deeper and deeper’

When two Georgia correctional officers were shot and killed last June by two inmates who had escaped from Baldwin State Prison, Young had what he describes as an “awakening.”

At a gathering of ASMP staff members, he asked for documents referring to the security problem and ultimately received nearly 100 pages of material, which he passed on to the AJC and The Augusta Chronicle.

The documents covered a multitude of incidents, including one in which a manager from Georgia Correctional HealthCare reported seeing an inmate masturbate in front of a nurse at the pill call window and another in which three nurses described the terror of being in the prison’s crisis stabilization unit when an inmate escaped.

Young said he also learned during his inquiry that the lock on the door to the operating room had been broken for four months and that the OR had fallen into general disrepair.

“I was told, `Well, we have these other problems too,’” he said. “And from there, it just went deeper and deeper.”

Around the same time, he said, his clinic was without an orderly to clean it for two weeks. The situation became so dire, he said, that he had to clean the toilets himself.

Using Clorox wipes to remove filth from toilets that “looked like something you’d find in a truck stop” brought him to a crossroads, Young said.

“At that point I realized that, without some kind of outside intervention, nothing substantive ever was going to change there,” he said.

In October, Young filed a complaint with the National Institute for Occupation Safety and Health. The agency researches worker health and safety issues as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The complaint led to an exchange of emails between Young and an industrial hygienist working for NIOSH in which the hygienist said she was willing to visit the facility if the Department of Corrections would allow it.

That clearance has yet to be granted.

Deciding to go

As the year ended, Young said, events unfolded that made him believe he had become “radioactive.”

On Dec. 20, he said, he received a visit from Dr. Mary Sherryl Alston, the medical director at ASMP. He said she told him that Georgia Correctional HealthCare would be evaluating whether his position was necessary.

He said Alston spoke vaguely, saying only that “they” would be making a decision, but he perceived her to mean his job was in jeopardy.

Alston did not respond to an email seeking comment. Engel wrote that there was no attempt to eliminate Young’s position and that he had sought to resign previously and had been asked to stay on because of the quality of his work.

The next day, Young said, a correctional officer refused to bring an inmate recovering from a stabbing from lockdown to the outpatient clinic so his dressings could be changed. Young said he tried to take the matter directly to the prison’s new warden, Ted Philbin, and was stalled for two hours by the warden’s secretary.

“I’ve never been somebody to play the doctor card,” he said. “But, for Christ’s sake, I’m the outpatient clinic medial director and I’ve got a secretary telling me I can’t talk to the warden?”

A day later, Young wrote his letter of resignation. The document runs nearly 500 words and in places is highly personal. He wrote that he has suffered seven respiratory infections in the last 18 months, a condition he suspects can be attributed to the mold and other environmental issues.

“I wrote this with a purpose,” he said. “Otherwise, I could have said, `Screw you guys, I’m not coming back here.’”

Young also works for an Augusta urgent care company and in a rural hospital emergency room, so leaving ASMP won’t have much of a bearing on his career. But he admits he worries about those still working there and whether things will improve for them.

“I’ve heard some things are being done,” he said. “But are they long-term fixes? I have no confidence in that. What that place requires is beyond what the people there are capable of doing.”

In addition to spotlighting concerns about sanitation and security at Augusta State Medical Prison, AJC investigations have called into question the medical care provided to inmates throughout the state prison system. These are some of those stories:

» A massive backlog of requests for medical tests or consultations has left some inmates waiting months for essential care.

» Healthcare workers at Macon State Prison alleged that the doctor there deprived inmates of treatemnt even as horrific infections spread. The state later agreed to pay $550,000 to an inmate whose leg had to be amputated after a wound became infected. Following the settlement, the physician retired.

» The death toll of female inmates under the care of Dr. Yvon Nazaire grew last year to 11. An AJC investigation in 2015 detailed how nine women in Nazaire's care at Pulaski State Prison and Emanuel Women's Facility died under questionable circumstances. He was later fired.

» Georgia hires a disproportionate number of prison doctors with troubled pasts. Among the doctors the state has hired is one barred by the medical board from doing any type of surgery after it found that a number of women had experienced serious complications, including infection and disfigurement, after breast augmentation procedures.

» Deliberate indifference to inmates' medical needs is a violation of the 8th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled.

Coming Monday: The top Georgia Department of Corrections health official tells the AJC his plans to fix ASMP.

About the Author