Spread of coronavirus has Georgia’s booming poultry industry on edge

This story has been updated to include comments from Tyson Foods

Tara Williams is anxious and, she says, so are her 2,100 co-workers at the Tyson Foods plant in Camilla.

In the weeks since the COVID-19 pandemic hit, killing more than 30,000 Americans, three of her co-workers at the poultry plant have died from the virus.

Tyson, like dozens of other meat processing plants in Georgia, has taken steps to improve safety, but workers are still concerned and the industry is nervous.

“I don’t think Tyson is doing what they can or should do. It is kind of like a little too late,” said Williams, who works the overnight shift at Tyson. “And the anxiety is high among employees. We are still scared, we are still having people calling out sick, and those of us who come to work, still have to mingle.”

Suzzette Bradfield has been working in and around poultry plants for more than 30 years selling inspection equipment . She said nothing has shaken her more than the possibility of what the coronavirus can do to the industry.

“When these people start getting sick, they are gonna have to shut plants down to clean them,” said Bradfield, the owner of Southeastern Packaging Equipment Sales, and who works with nearly every poultry plant in Alabama and Georgia. “And they have a hard enough time getting workers anyway.”

National Concerns

More than 654,000 Americans have been diagnosed with the virus that has killed more than 31,000. A disproportionate number of those who have died have been black and Latino.

Those demographics have seeped into the meatpacking industry.

Several major meat processing plants have had to shut down as workers, mostly black, Latino and immigrants, continue to get sick.

Earlier this month, Smithfield Foods, one of the country’s largest pork-producers, indefinitely closed its plant in Sioux Falls, S.D., after nearly 300 of its employees tested positive for COVID-19. JBS USA, Cargill and Tyson foods have closed plants across the country and in Moultrie, more than 400 Sanderson Farms poultry plant workers were sent home with pay due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The closings represent a fraction of the country’s food production, but many industry experts fear that with the walkouts, illnesses and deaths, the nation’s meat supply might soon come under threat.

Elbow to elbow

But Mike Giles, president of the Georgia Poultry Federation, said he has not seen any indication that widespread closures could come to Georgia. Nor has he seen a reduction of productivity. Georgia, the leading poultry producer in the nation, accounting for $42 billion into the state’s economy, is still producing over 31 million pounds of chicken and 7 million table eggs daily to restock the supply chains that feed Americans.

There are 18 major plants in Georgia that process about 1.2 million live chickens a week and about 25 smaller plants that do additional processing.

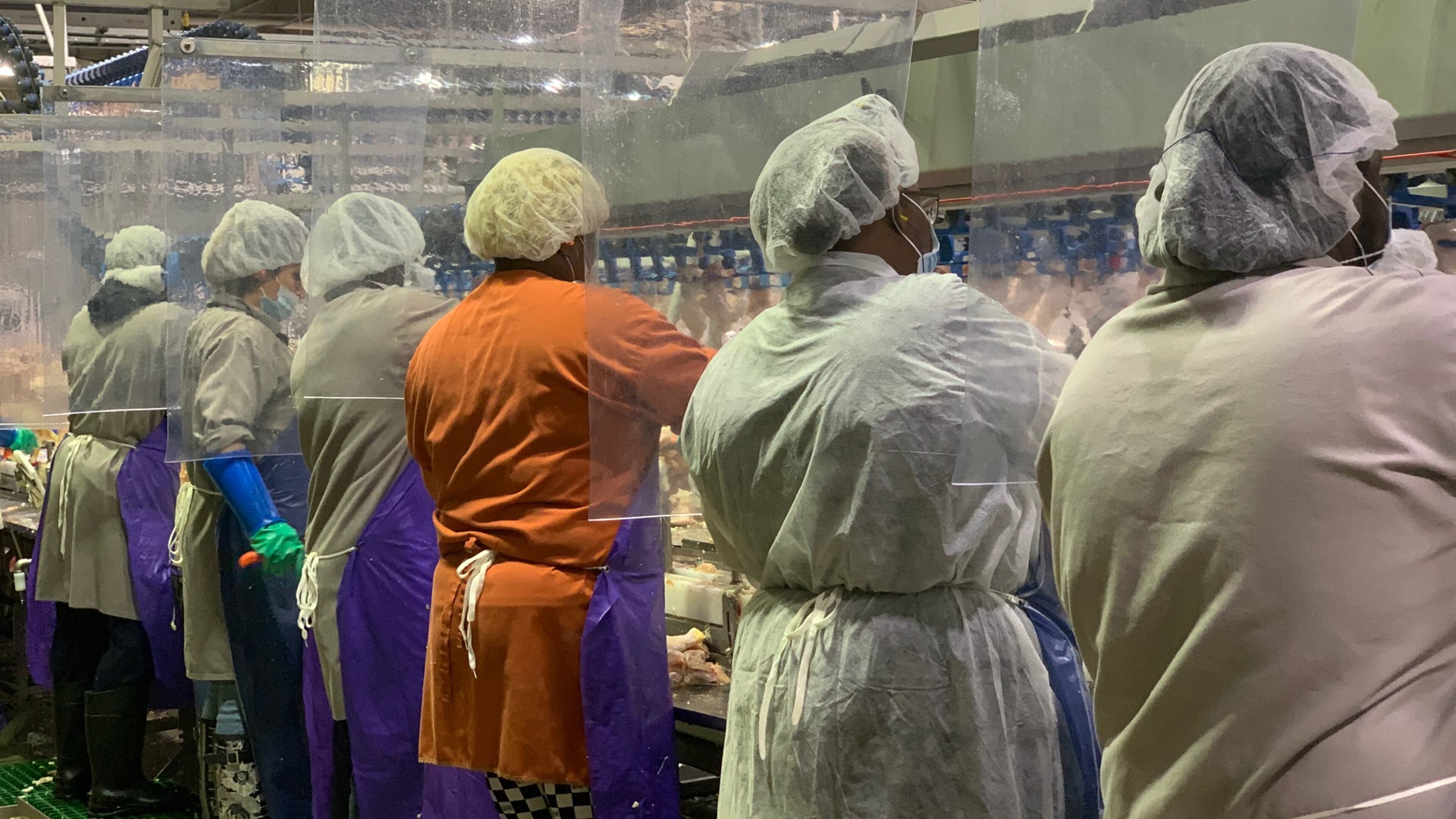

The industry employs approximately 40,000 people who generally operate in close quarters deboning and packing chicken.

As many as 60 people can be on a line, “Elbow to elbow, cutting chicken. Turning, breathing on each other and coughing. This is hard work on a good day,” said Edgar Fields, president of the Southeast Council of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

It is unclear how many of the state’s poultry workers have been diagnosed with COVID-19.

But Giles said plants across Georgia have enhanced sanitation routines at processing facilities.

Although there has not been a uniformed mandate for all plants to do the same things, they each are doing things that suit their facilities Giles said.

Pilgrim’s Pride, which employs 7,000 workers in seven Georgia plants, told the AJC that among other things, the company has increased sanitation and disinfection efforts with daily deep cleanings; started temperature testing for all workers entering facilities; relaxed attendance policies so people don’t come to work sick; and enforced physical distancing by staggering starts, shifts, and breaks and installing large tents for more spacing during lunch breaks.

At Tyson Foods, which has recorded Georgia's three poultry worker deaths, senior vice president for human resources Hector Gonzalez, said the company is "constantly looking for ways to improve."

“We’re working diligently to protect our people by taking their temperatures and have installed infrared scanners to help. We’re requiring protective face coverings and deep cleaning our facilities," Gonzalez said. "We’ve implemented social distancing measures, such as installing workstation dividers and providing more breakroom space. In March, we relaxed our attendance policy to encourage workers to stay at home when they’re sick."

Fields, who represents workers in Camilla, acknowledges that changes have been made, industry-wide, including at Tyson. But wonders if it is enough and in time.

“Tyson is doing the things we wanted them to do, but many are saying too late,” Fields said. “We still lost three people. People are still very afraid to go to work.”

Located just 25 miles south of Albany, a hotspot, where more than 1,893 people have been diagnosed with coronavirus and close to 70 have died, Camilla is about 65 percent black and a majority of the plant workers are African American.

Tyson workers make between $12 and $15 an hour at a job that in most cases is the best they can get in the area. Generations of families have worked there.

“Each day these people get up and go to work they are putting their life on the line to feed the country,” Fields said.

Fear in Gainesville

Nowhere is that felt more than about 50 miles northeast of Atlanta in Gainesville, “The Poultry Capitol of the World.

Half of the city’s top 10 employers are poultry plants.

According to census figures, 40 percent of Gainesville’s 41,464 residents are Hispanic and 25 percent of the population is foreign-born. According to Pew 12 percent of Gainesville’s total population – the highest in the nation — and 65 percent of all foreign-born residents are undocumented immigrants.

Hispanics account for a majority of COVID-19 positive cases in Gainesville and Hall County and with that comes a growing fear of cluster outbreaks in food processing plants.

“Latinos are the most affected,” said Vanesa Sarazua, founder and executive director of Hispanic Alliance Georgia. She has been trying to track the number of cases and deaths from COVID-19 in the Hispanic community, which has been difficult because those who are undocumented are reluctant to seek help. “They are afraid of the charge and afraid to go to the hospital and being left there to die alone. They are basically at home until the very end.”

At least five people in Hall County have died from the virus.

About a dozen members of Maria Palacios’ family, including her parents, work in poultry plants around Gainesville. A local activist in the Hispanic community, Palacios said several of her family members have been sick, although none have been tested or diagnosed with the virus.

They tell her of plants that are short-staffed because so many people are calling in sick. Those still going to work “are still expected to complete the full production,” Palacios said.

“My family, all they do is sleep,” Palacios said. “They wake up, have dinner, sleep some more, wake up and go to work. I don’t think it is sustainable, but they are all afraid of losing their jobs. It is very stressful, and people are very concerned.”

Annie Grant

In late March, Willie Martin got a Facetime call from his mother, Annie Grant, who was sitting in the parking lot of the Camilla Tyson plant.

The 55-year-old Grant had been out sick for a couple of days and told her son that she was being ordered back to work.

Someone took her temperature.

She didn’t have a fever and was sent back to her job of 15 years, packing chicken for shipping for $14 an hour.

She didn’t stay long.

Less than an hour.

Her family checked her into a hospital, where she would spend more than a week on a ventilator.

By April 9, Grant was dead.

Each of the three people who died at the Tyson plant were black women.

“We’re heartbroken over the loss of team members from our family at Camilla," Gonzalez said. “We realize everyone is anxious during this challenging time and believe information is the best tool for combating the virus. That’s why we’re encouraging our team members to share their concerns with us, so we can help address them."

Martin, who coaches high school football in Sumter, S.C., grew up in Camilla and knows how important the plant is to the livelihood of the community.

“I am highly disappointed with what happened with my mom,” Martin said. “That plant supplies a lot of families. I really would like to see them take precautions and look out for the safety and well-being of the workers.”

Martin will bury his mother on Saturday.