El Refugio provides comfort to visitors of immigrant detainees

At 3 a.m. on a Saturday morning, Iris Abarca pulled herself out of bed at her home in Raleigh, North Carolina, to begin the 600-mile drive to southwest Georgia.

Around midday, wearied by the monotony of the highway, she and a friend pulled into the small town of Lumpkin, a half-hour south of Columbus, anxious about their upcoming visit to Stewart Detention Center.

Luckily, they were met by a friendly face.

Marilyn McGinnis greeted them at the door to El Refugio, a little yellow house just a mile from the immigration detention center. McGinnis offered food, drink and a place to stay the night.

“It’s a place to have a little bit of respite and support,” said McGinnis, an Atlantan who has volunteered at the house on weekends since it first opened in 2010.

El Refugio provides a ministry of hospitality and visitation to the detainees at Stewart Detention Center, a private prison contracted by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to detain immigrants. It holds about 1,700 men. The house offers a free place to stay for families and friends, many of whom have driven from out of state, to visit their loved ones held at Stewart. Some visitors are strangers to the detainees, volunteers who bring hope and diversion to those who have no visitors.

Abarca put her backpack on a bunk in the front bedroom and talked about her friend in detention.

“We go to the same church,” Abarca said. “He plays drums for the church band.”

The 34-year-old electrician was picked up by ICE the Thursday before Easter after being involved in a car accident, she said. He had come to the United States with his family at age 14 from Xalapa, Mexico, and was undocumented.

It was hard seeing him alone, depressed and worried about his future, she said.

He had expected to be bailed out two days earlier, but the hearing was postponed, Abarca said.

He told her: “I just want people to stop feeling sorry for me. I just want this to be over,” she said.

That same Saturday, the day before Mother's Day, volunteers at El Refugio assisted another woman visiting at Stewart. She was so concerned about her son's mental health, El Refugio officials say, she asked a volunteer to visit him on Sunday, but the volunteer was turned away when she attempted to visit.

The following day, the mother’s 27-year-old son, Jean Carlos Jiménez-Joseph, hanged himself after 19 days in solitary confinement.

In response, El Refugio issued a statement saying detainees at Stewart experience prolonged detention in dehumanizing conditions, an assertion denied by ICE and CoreCivic, the company that runs Stewart Detention Center. The facility is one of four in Georgia and one of the largest in the nation.

El Refugio wants detainees to know they are not forgotten.

Men are detained for a variety of reasons at Stewart. Some are held after serving time for committing felonies. Others have traffic violations. Still others came here seeking asylum. Most detainees are simply guilty of being undocumented.

In a sense, the center in South Georgia is out of sight and out of mind for most Georgians. But not for El Refugio.

The house has three bedrooms filled with bunk beds, providing sleeping space for 21 people, including the living room sofas. Mexican and Central American artwork adorns the walls, along with framed letters from grateful guests.

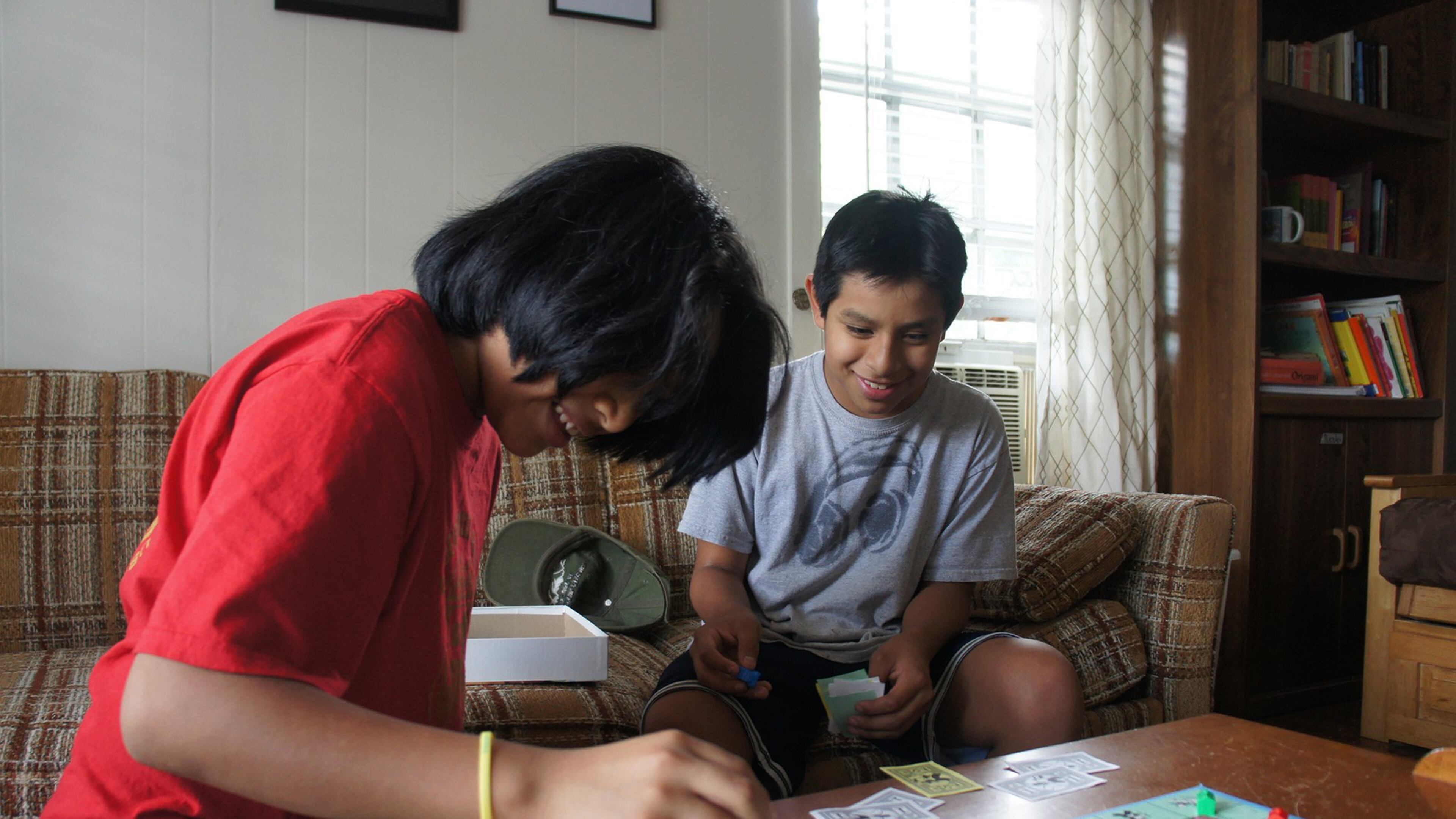

In one corner of the living room, next to a fat potted plant, children play with games and colorful Fisher-Price toys. Snacks for visitors overflow in the small kitchen.

The house is open on Saturdays and Sundays.

Laura Mercado drove down from South Carolina with a friend. The friend’s son had been sent to Stewart less than two weeks earlier.

“He was stopped for not having a headlight,” Mercado said of the undocumented Honduran. His mother, who is married to a U.S. citizen, is in the process of getting a green card, Mercado said.

“We’re waiting for him to see the judge to see if we can bail him out,” Mercado said.

A 2016 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center suggests that immigrants detained at Stewart fare worse than those at other detention centers. Of those seeking asylum, 6 percent receive asylum compared to 48 percent nationwide. Less than 8 percent of detainees at Stewart are granted bond, compared with the national average of 10 percent.

About half the detainees are from Central America. Others come from Africa and Asia.

El Refugio was started by a faith group in LaGrange known as Alterna. Loosely affiliated with the Mennonite Church, Alterna was co-founded by Anton Flores, a former faculty member at LaGrange College.

The organization is now a nonprofit directed by Amilcar Valencia, who has worked with nonprofits in both El Salvador and the United States.

Earlier in the spring, El Refugio hosted four members of Georgia State University’s Lambda Upsilon Lambda fraternity who came to visit Stewart as a community service project.

Returning from the detention center, they filed quietly into the house through the back door.

Immigration attorney Laura Glass-Hess, a volunteer that weekend, sat at the dining room table.

“How was it?” she asked.

“It’s a confusing emotion,” said student Luis Beltran. “It’s not a good feeling you get listening to them. You feel very privileged in your life.”

Beltran had talked for an hour with a detainee from Cameroon, the two separated by a glass window, speaking on a phone.

“His country is in conflict,” Beltran said. The detainee had come into the United States without authorization and had been picked up by immigration authorities in Texas. He was held there several months, then transferred to Stewart, where he’s been for six months.

He’s had two visits, Beltran reported, from his aunt and his fiancée.

“He was a smart guy,” Beltran said, an electrical technician who said he couldn’t find work in his country.

He believes he will be jailed if he returns because he’s criticized the government, Beltran said.

Student Roberto Contreras-Murillo was equally somber. He’s a junior at Georgia State studying health and physical education, with the goal of teaching and coaching. He visited a young detainee from El Salvador.

“I’m only a year older than him,” Contreras-Murillo said. “He was going to college in El Salvador.”

The detainee said the police tried to extort money from him and he fled his country. He’s been in Stewart for eight months.

“It’s just kind of crazy,” Contreras-Murillo said.

Glass-Hess nodded her head. “You think: These people are in jail. They must be different from us.” But when you visit them, she said, it’s easy to relate to them.

The four students from Georgia State found the experience “eye-opening,” Beltran said.

“What feels so bad about this is that [some] people are being punished for doing something that is not innately wrong,” he said.

RELATED STORIES