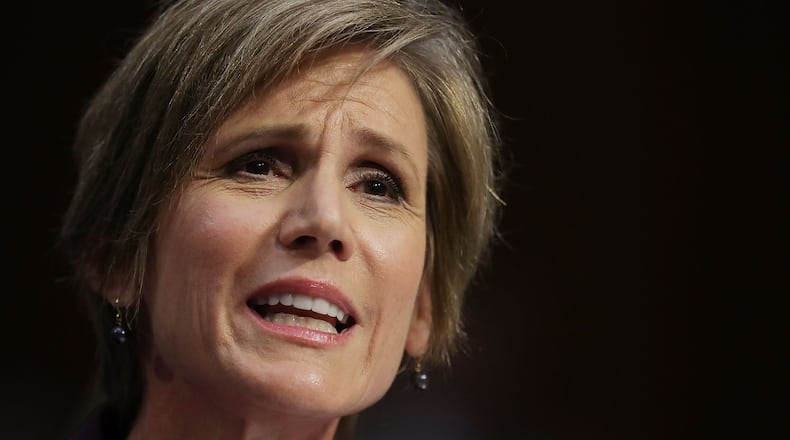

Sally Yates catapulted into the national spotlight when President Donald Trump fired her in late January as his acting U.S. attorney general. Liberals swooned across the internet, praising her independence for refusing to defend Trump's travel ban. Conservatives attacked, branding Yates a headline-hunting partisan hack.

Having made no public comments since her ouster, Yates appeared Monday before the Senate Judiciary Committee's subcommittee on crime and terrorism in one of the most anticipated events on Capitol Hill this spring. She didn't disappoint.

Throughout the high-stakes, three-hour hearing, Yates disposed of the most hostile questions with the same equanimity and poise that she evinced when fielding softballs from friendly subcommittee members.

"She was Sally," said Kent Alexander, who preceded Yates as a U.S. attorney in Atlanta. "It's not like she had to put on an act. She's always fully prepared and knows what the arguments are and what the facts are."

A similar picture of Yates emerges from AJC interviews with people who know her well, from a classmate at Dunwoody High School to a prominent Atlanta defense attorney who has watched her dismantle witnesses on the stand to former colleagues in the Justice Department.

“She’s been like that forever,” said Janet Allen Johnston of Yates’s “cool as a cucumber” performance Monday. Johnston and Yates have been friends since they were classmates at Shallowford Elementary School.

She recalled that when they attended Dunwoody High, Yates put in to be on Rich’s department store’s “teen board,” whose members got to model clothes at the store downtown.

“She was one of the ones who got picked, of course,” said Johnson, an American Airlines flight attendant in Dallas. “She was the whole package — pretty, smart and always had it together.”

‘I think Sally Yates did her job’

Reviews of Yates's appearance on Monday ranged from adulation to accusation. "We built her up that day and laid offerings at her feet in the night," said an op-ed writer in the New York Times Friday. An opinion piece in the New York Post carried the headline "Sally Yates was the real blackmailer."

At the hearing, Yates recounted how she notified the White House that Vice President Mike Pence was making false public statements because then-national security adviser Michael Flynn had lied to Pence. This "compromised" Flynn, making him vulnerable to blackmail by Russia, Yates said.

Before the hearing, Trump tweeted, “Ask Sally Yates, under oath, if she knows how classified information got into the newspapers soon after she explained it to W.H. Counsel.” Under oath, Yates was asked just that, and she steadfastly denied sharing classified information with the news media and said she did not know how it happened.

Yates, 56, also stood by her decision not to defend Trump’s executive order, parrying questions from Republican senators who are still angry about it. “I believed that any argument that we would have to make in its defense would not be grounded in truth,” she said.

During a press briefing Wednesday, Trump spokesman Sean Spicer called Yates a “political opponent of the president” and someone who “refused to uphold a lawful order of the president.”

But subcommittee chairman Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said he found Yates to be credible. “I think Sally Yates did her job so I was very pleased with her testimony,” he said.

Subcommittee member Dick Durbin, D-Ill., agreed. “Perfect — a 10,” he said of her testimony.

Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., perhaps Yates’ most hostile inquisitor, said Yates was grandstanding when she defied the travel ban. “She should have resigned if she felt that strongly, not wait to be fired and get a bunch of headlines,” he said.

Since the day she was fired, Yates has made many headlines while steadfastly refusing to comment publicly. This includes turning down repeated requests by the AJC for an interview.

She's become so popular among Georgia Democrats that many are hoping she'll run for political office. Yates has yet to make her intentions known.

A legal pedigree, and a personal tragedy

Yates’s lineage is the law. Her grandfather served on the Georgia Court of Appeals and the state Supreme Court. Her grandmother was one of the first women admitted to the Georgia bar. And Yates’s father was a Court of Appeals judge for 18 years.

But Kelley Quillian would not live to see his daughter graduate from the University of Georgia Law School.

Yates’s mother told the police that her husband had been despondent for months leading up to his suicide, which came just a few days before Sally’s graduation.

"The manner in which he died was heartbreaking," Yates told the AJC in a prior interview. "But there were a whole lot of years prior to that which were not about that. As I think back on my dad, that's what I really think most about — those years when he lived with a vitality that most people never even come close to."

Quillian left at least one piece of unfinished business, and his daughter decided to take it up on his behalf.

In 1985, Quillian had filed suit against the state employees’ retirement system, which had assured him he would receive $57,457 a year as a retired judge. But that sum turned out to be the highest pension for any state retiree at the time and, amid public criticism, the state decided to recalculate it. Quillian’s pension went down by 36 percent.

He died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound one year and four days after filing the lawsuit.

John Larkins, an attorney for the firm that represented Quillian, asked Yates whether she’d like to work on the case, now proceeding on behalf of her mother. Yates jumped at the chance.

The Georgia Supreme Court voted unanimously in 1989 to restore Quillian’s pension in full.

Up to that point, Quillian’s lawyers had not put Yates’s name on the court pleadings because they didn’t want judges to think they were angling for sympathy. But after the high court’s ruling, Larkins filed a motion to include Yates’ name with the other lawyers’ on the decision. The court granted the request, and the name “Sally Quillian” is on the opinion.

“She was determined to vindicate her father’s career,” Larkins said.

Credit: John Spink

Credit: John Spink

Discovering justice at her first trial

By that time, Yates was a young associate at King & Spalding, one of Atlanta’s top law firms. It was there she met Comer Yates, her future husband.

In the mid-1990s, Comer, with Sally often by his side, twice ran unsuccessfully as a Democrat to represent Georgia’s 4th District in the U.S. House. Since 1998, he has been executive director of the Atlanta Speech School. They have a son, Quill, and a daughter, Kelley.

While at King & Spalding, Yates agreed to take on a case that would lead to her first trial and become the most meaningful case of her career. The client was Lovie Morrison, 93, and Yates worked for free.

In the 1930s, Morrison became Barrow County’s first African-American landowner. Mistrustful of the all-white county courthouse, she failed to timely file her deed, Yates told students during a 2016 commencement address at UGA Law School.

By the time Morrison did record the deed, a developer was planning to build a subdivision on 6.2 acres of her land. Yates filed suit to get the property back.

At the time, Yates had never sat through a real trial in court. Legendary King & Spalding lawyer Charlie Kirbo, President Jimmy Carter’s one-man “kitchen cabinet,” took her under his wing. Kirbo sat next to her at counsel table and demonstrated “a profound commitment to justice,” Yates said.

At trial, the developer’s lawyer struck all the African-Americans from the jury pool, leaving Morrison and her daughter as the only two blacks in the courtroom, Yates said. Even so, the jury returned a verdict in Morrison’s favor.

The case didn’t make headlines, Yates said. “It wasn’t about a lot of money and we didn’t establish any new legal theories. But this experience demonstrated to me how powerful unlocking justice can be.”

‘She’d destroy people on the stand’

Yates left King & Spalding after three years to become a federal prosecutor in Atlanta. Although she planned to be there for a few years to get some trial experience, she would remain with the Justice Department for 27 years, until Trump showed her the door.

“The fact of the matter is, as corny as it sounds, once I had experienced the privilege of representing the people of the United States, it was hard to imagine going back to representing any other client,” she told the UGA law students.

Credit: John Spink

Credit: John Spink

Four years into her tenure, Yates shook the city of Atlanta’s power structure to its core. She obtained an indictment that alleged a scheme involving at least $1 million in bribes to influence contracts for airport gift shops.

Two city officials – a former City Council member appointed to run the airport and a sitting council member – were convicted of bribery, mail fraud and tax evasion. Three others were convicted of paying the bribes.

“The Sally Yates who prosecuted the airport corruption case almost 25 years ago and the Sally Yates who testified Monday, those aren’t the same person,” said Doug Blackmon, who covered the case for the AJC.

“They’re closely related,” said Blackmon, now a senior fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. “The prosecutor of 25 years ago had the same slightly scary resolve — a sharp, immovable resolve — and a conviction that if I’m prosecuting you for a crime, there will be no holds barred. She’s now had an endless number of experiences that have hardened and even sharpened that resolve.”

Yates continued to successfully prosecute high-profile cases involving both Democrats and Republicans — Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell, Fulton County Commission Chairman Mitch Skandalakis and state school Superintendent Linda Schrenko.

Atlanta defense lawyer Jerry Froelich, who obtained the only acquittal in the airport case and defended Campbell, said the Senate subcommittee was fortunate Yates wasn’t asking the questions on Monday.

“Her cross-examinations were so good,” Froelich said. “She’d destroy people on the stand. Brutal. Just brutal.”

Testy exchange with Ted Cruz

But on Monday, Yates was the one being grilled, and Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, was especially testy.

When Yates suggested Trump’s travel ban was discriminatory and that the president’s executive order violated the Constitution, Cruz shot back: “There is no doubt the arguments you laid out are arguments that we could expect litigants to bring, partisan litigants who disagree with the policy decision of the president.”

Yates didn’t falter. This was “about a fundamental issue of religious freedom — not the interpretation of some arcane statute, but religious freedom,” she said.

Moments later, Yates acknowledged the deep disagreement about her handling of the travel ban. But she didn’t apologize.

“Look, I understand that, you know, people of good will and who are good folks can make different decisions about this,” she said. “I understand that. But all I can say is that I did my job the best way I knew how.”

Staff writer Tamar Hallerman contributed to this story.

Sally Quillian Yates

Age: 56

Career: King & Spalding, associate, 1986-1989; U.S. Attorney's Office in Atlanta (assistant U.S. attorney, chief of fraud and public corruption section, first assistant U.S. attorney and acting U.S. attorney) 1989-2010; U.S. Attorney in Atlanta, 2010-2015; deputy U.S. attorney general, 2015-2017; acting U.S. attorney general, Jan. 20-Jan. 30, 2017.

Education: University of Georgia, bachelor of arts, 1982; UGA School of Law, magna cum laude, 1986

Personal: Married to Comer Yates, executive director of the Atlanta Speech School. They have two children.

Yates’ back and forth with Cornyn

During Monday’s hearing, a number of Republican senators took exception to Sally Yates’ decision not to defend President Donald Trump’s executive order on the travel ban.

Here is Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, telling Yates how he felt about it.

Cornyn: Well, Ms. Yates, you had a distinguished career for 27 years at the Department of Justice and I voted for your confirmation because I believed that you had a distinguished career. But I have to tell you that I find it enormously disappointing that you somehow vetoed the decision of the Office of Legal Counsel with regard to the lawfulness of the president's order and decided instead that you would countermand the executive order of the president of the United States because you happen to disagree with it as a policy matter. … I just have to say that.

Yates: I appreciate that, Senator, and let me make one thing clear. It is not purely as a policy matter. In fact, I’ll remember my confirmation hearing. In an exchange that I had with you and others of your colleagues where you specifically asked me in that hearing that if the president asked me to do something that was unlawful or unconstitutional and one of your colleagues said or even just that would reflect poorly on the Department of Justice, would I say no? And I looked at this, I made a determination that I believed that it was unlawful. I also thought that it was inconsistent with principles of the Department of Justice and I said no. And that’s what I promised you I would do and that’s what I did.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured