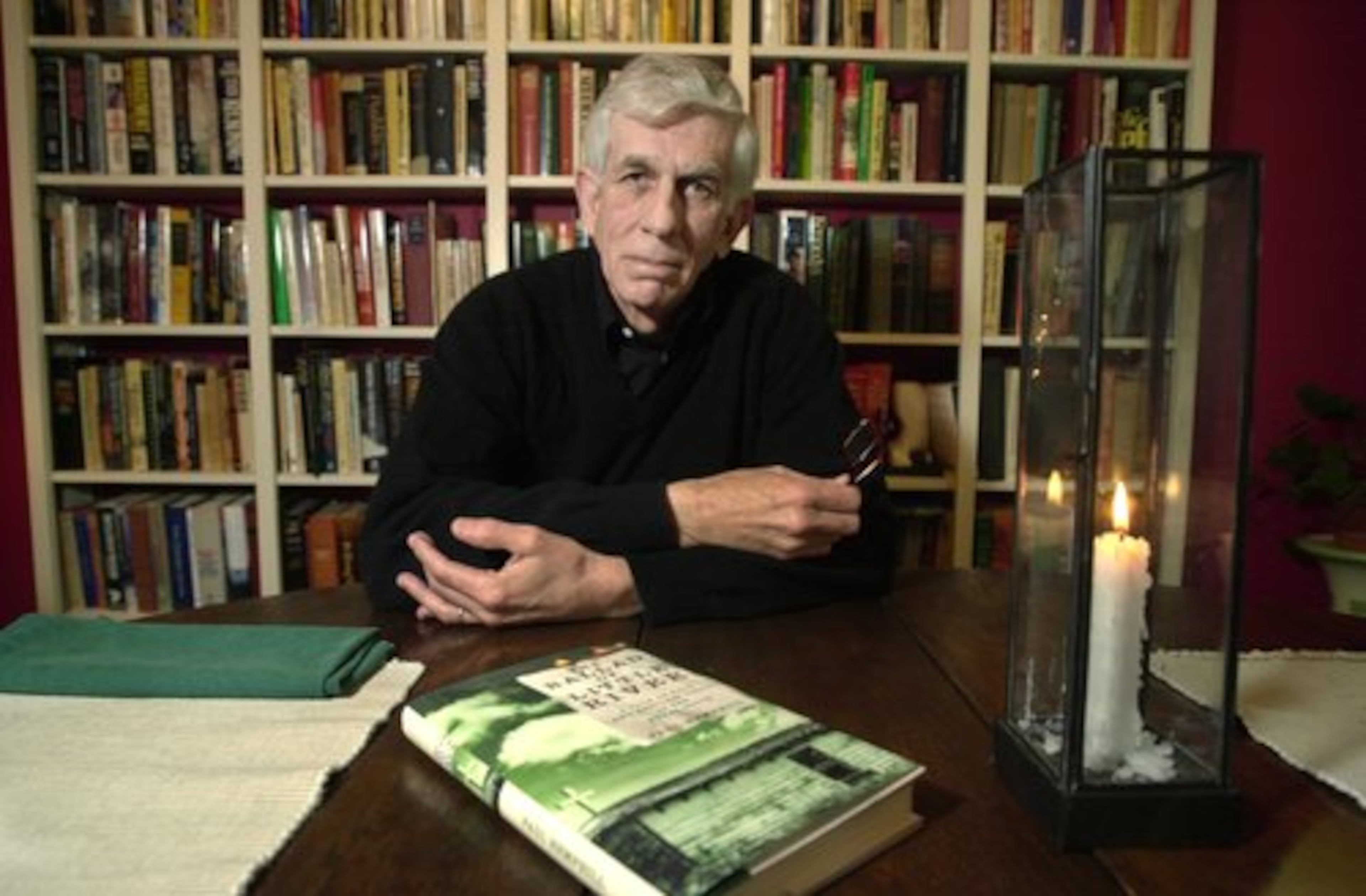

Atlanta writer Paul Hemphill focused on the blue-collar South

It was said of country music legend Hank Williams that he wove his magic using “three chords and the truth.”

Atlanta writer Paul Hemphill, whose critically well-received biography of Williams was one of his last books, worked that same magic.

As a columnist and author, Hemphill entranced readers chronicling the blue-collar South. He wrote about stock cars and country music, church burnings and church evangelists. His 15 books, including nonfiction work and novels, reverberated with all the twang and tears of a Hank Williams tune.

Hemphill died early Saturday, July 11, 2009. He was 73. He had spent some time in hospice care, after cancer moved from his mouth to his lungs.

The rangy Southerner grew up in Birmingham, the son of a long-distance trucker. He loved the Birmingham Barons and Rickwood Field but rejected the city's racist heritage and his father's bigotry. He wrote of that parting in his memoir, "Leaving Birmingham," published in 1993.

"He said goodbye to the attitudes of his history but he didn't say goodbye to his history," said Cliff Graubart, owner the Old New York Book Store, who hosted many book-signings for the writer.

As a young man Hemphill dreamed of playing baseball but he washed out of the Graceville Oilers (a Class D Florida team) in the first days of spring training. Instead he ended up at the Alabama Polytechnic Institute, which became Auburn University, where fellow undergrad Anne Rivers Siddons remembers seeing the rawboned, aspiring journalist trying out for the student newspaper, the Plainsman.

"I remember a kid with enormous ears and this huge grin," she said.

He served with the Alabama Air National Guard, and worked in public relations. Journalism took him to a handful of smaller newspapers, until he arrived in Atlanta in 1964.

Brought to town by the Atlanta Times, he was hired away by the Atlanta Journal to write a Page 2 column six days a week. His columns took him all over town, the Southeast and as far afield as Vietnam.

Hemphill didn't always voice the boosterism that typified Atlanta in the 1960s.

"We were blowing our horn so hard we were just about ready to fall over backwards," remembers Siddons, another transplant to Atlanta who became a successful novelist. "I expect he made a lot of people mad. He was what we needed at the time."

Longtime Atlanta journalist Lee Walburn, who covered baseball for the Journal during that period, says Hemphill's columns were "appointment journalism. You almost had to pick up the paper to see what he was going to write about that day.

"He was Grizzard before Grizzard was cool."

But while humor columnist Lewis Grizzard, who followed in Hemphill’s footsteps, earned national syndication and a sizable income, Hemphill left the daily column behind after a few years. During a Nieman Fellowship to Harvard University in 1968-69, he researched and wrote his first book, “The Nashville Sound.” Though he returned to the newspaper for a while, the column lost its charm. He wrote a dramatic resignation letter one day during a bibulous lunch at Emile’s French Cafe downtown.

The book, which came out a few months later, sold 75,000 copies in hardcover and was hailed as a groundbreaking look at country music and the Grand Ole Opry. Country music itself was on the verge of a commercial transformation.

"He had no idea that the end of an era was coming," said Frank Reiss, owner of A Cappella Books, whose small press, Everthemore, reprinted the Nashville book in 2005. "He captured it before it really went glitzy . . . it was one of the first seriously good books about country music."

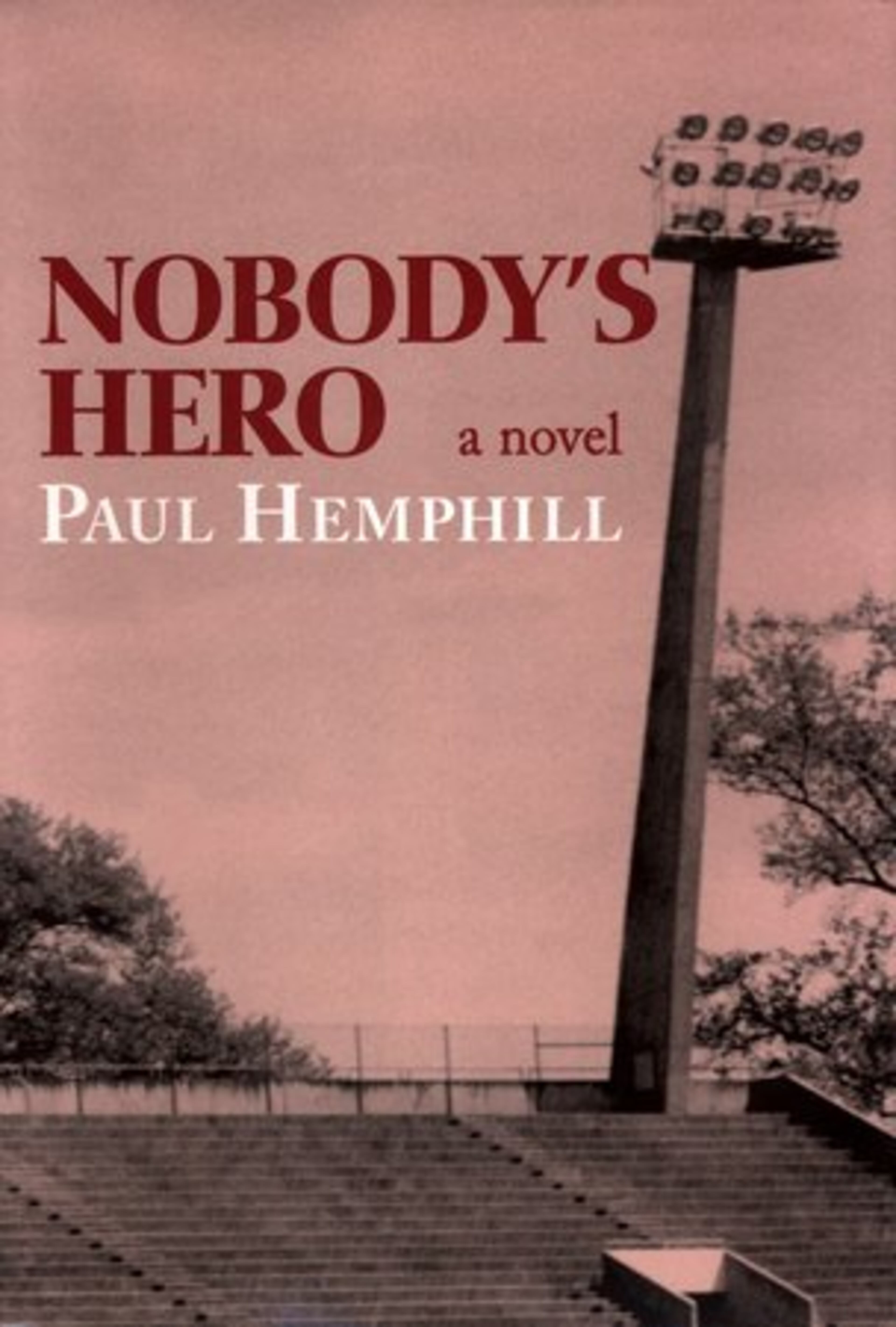

A string of books followed. Hemphill was consistently praised by reviewers at the New York Times, though none of his subsequent work did as well on the shelves as his first effort.

Hemphill collaborated with former Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen on Allen's autobiographical account of the turbulent 1960s. His novel of minor league baseball, "Long Gone," was eventually made into an HBO movie, starring William L. Peterson and Virginia Madsen.

He documented his own struggles with alcohol and his uneven father-son relations in "Me and the Boy," an account of an attempt by Hemphill and his son David to hike the length of the Appalachian Trail.

Hemphill taught writing at Emory University, the University of Georgia and elsewhere.

"Paul's talents as a storyteller and author were widely regarded but he also became a respected teacher of journalism," said John English, professor emeritus at UGA. "His credibility with college students was obviously enhanced by his successful professional writing career."

While he enjoyed helping younger writers, his impact on the craft probably came mostly through example, said Georgia novelist Terry Kay.

"What he really had was a good ear," said Kay. "He had a sense of what made dialogue and he had a sense of the characters he was working with because of the way they used dialogue."

Ill health struck in 2005 just as "Lovesick Blues: The Life of Hank Williams" came out.

Hemphill had a stroke that year, followed by mouth cancer. A lifelong smoker, Hemphill was already trying to kick the habit but by then, it was too late. The cancer moved to his lungs this year.

Yet he kept writing and kept holding court at Manuel's Tavern, the Southeastern headquarters for unregenerate journalists and Democrats.

Before going into hospice care, he spent his last days at home with wife Susan Percy, editor of Georgia Trend magazine. When he was too ill to go out, his friend Jack Wilkinson would bring him a vanilla shake from Steak and Shake and tell stories about baseball outings at the Rickwood Classic in Birmingham.

Though a Birmingham native and a sojourner elsewhere, Hemphill holds a special place among Atlanta's laureates, said Siddons. "He is uniquely Atlanta's son."

Funeral arrangements are being coordinated by A.S. Turner & Sons in Decatur.

LEARN MORE

Paul Hemphill added to Atlanta Press Club Hall of Fame in 2021