This story was originally published on myAJC.com on Sept. 28, 2016, five days after Roy Faulkner, the man who carved Stone Mountain’s Confederate monument, died.

It's a warm day in September and, with the help of an aluminum walker and a female caregiver, The Man Who Carved Stone Mountain shuffles to a tan recliner in the living room of his daughter's Gwinnett County home.

A proud man who had a stroke in the '80s and has pushed through several smaller ones since, Roy Faulkner has a full head of wavy gray hair and wears an untucked dress shirt the color of sunbleached pollen. The 84-year-old doesn't — can't — talk much anymore, and his hearing is all but gone. But when his daughter shouts that a reporter has come to write a story about him, he guffaws and gives a thumbs up.

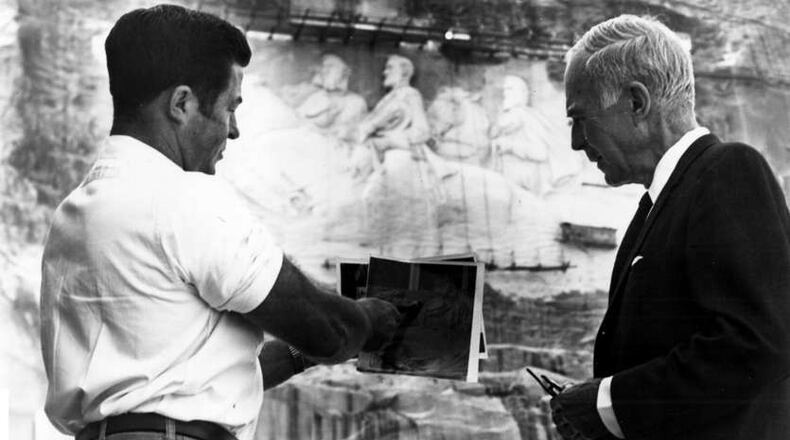

The daughter and the stranger then move to a cluttered kitchen table, where she waxes about her father's life while he sits and looks out the living room window, past his late wife's wedding portrait and the mantel-crowning painting that shows him giving a Confederate general a nose job with a blowtorch.

People around the state of Georgia — and the country — debate the merits of the man’s work, praise or decry the idea of a colossal carving that commemorates not heritage or hate but both. They call for it to be expanded, or sandblasted away, or counterbalanced by a memorial to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But they neither blame nor credit Roy Faulkner for its creation. Few know his name, or what he put into the carving.

His daughter recognizes this, and she knows what the mountain meant to him. She wants to preserve — or create — his legacy. So she's happy to speak with a reporter, and to promote the book she's written about her father's life. She relishes, too, another opportunity to hear him recite the precise amount of time he spent creating the American South's largest and most infamous piece of art.

With effort, it's one of the few things he can still utter.

"Eight years, five months and 19 days," Roy Faulkner croaks.

He would die 11 days later.

—

Roy Faulkner was born in a Newton County mill town in 1932, nearly a decade after work first began (and stopped) on Stone Mountain’s massive granite face. He was 4 years old when his father walked out, and his mother re-married several years later. They moved to a village at the Exposition Cotton Mills on the westside of Atlanta.

He had a paper route and made deliveries for a local pharmacy. At 17, he became a welder.

By 18, Faulkner was married — and a member of the United States Marines Corps. When his wave boat landed on a Korean beach, the two men standing in front of him were promptly killed. He ran ashore.

Faulkner returned home, fathered four children, moved to Covington. He worked for Atlanta Paper Company, then for Lithonia Lighting.

At age 32, a game of checkers would change his life.

—

Stone Mountain's Confederate memorial has a complicated backstory.

A sculptor named Gutzon Borglum began carving in 1923, completing Gen. Robert E. Lee's head before he spouted off in the papers about financial problems with the project. He had his contract cancelled (and went on to create Mount Rushmore). Another sculptor took over a few years later, sandblasted Borglum's work away and crafted the figures of Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

In 1928, the family that owned rights to the mountain — and had leased its face for the sculpture to be completed — reclaimed it all. It would be 28 more years before they relinquished it again.

In 1964, 99 years after the end of the Civil War, carving finally resumed. It was January when Roy Faulkner met a man named George Weiblen.

—

The chance meeting happened at Potts' General Store, a popular Covington gathering place on the road to Jackson Lake.

Over a checkerboard, George Weiblen informed Roy Faulkner that work was indeed starting again on Stone Mountain — and that he was assembling the crew. He needed a welder to build an elevator to aid in the carving. Faulkner fit the bill, applied and got the job.

Once he was on-site, it didn't take Faulkner long to see carvers' frustrations with their task. He suggested a shortened torch, and one powered by a mixture of kerosene, oxygen and fire — the compact, well-contained equivalent of a jet engine. It worked, but the carvers continued to struggle to create something so massive without the ability to step back and get some perspective.

Faulkner soon found himself in front of the chairman of the Stone Mountain Monument Committee asking to take on the project himself.

That worked, too.

"Welder" and $9.50 an hour quickly turned into "master carver" and $100 an hour. A man who'd never taken an art class — and had only ever watched as other men used carving torches nearby, for that matter — was now in charge of crafting the largest bas-relief sculpture on the face of the Earth.

RELATED: Who are the Confederate leaders carved into the side of Stone Mountain?

—

For the better part of a decade, Roy Faulkner strode across wooden planks hung hundreds of feet in the air, guiding a 4,000-degree thermo-jet torch in a mission to blast away centuries-old granite inch by inch.

He wore button-up shirts and a hard hat with a clear protective visor. Sometimes he wore ear muffs. There were 80-hour weeks. It was grueling and dangerous.

"The work on the memorial called for a man with agility and stamina, enough engineering skill to manipulate the scaffolds, and a daring nature that would let him enjoy spending several years 400 feet above the ground, where one misstep could be fatal," Willard Neal wrote at the time, in an article in The Atlanta Constitution.

On Aug. 1, 1966, a man named Howard Williams fell to his death. Faulkner's journal entry for that day would be his last, and it contained only two words: "Howard killed."

The carving was dedicated on May 9, 1970. It took two more years to remove the rigging, beams and scaffolding, however, and another man died in the process. His coat slipped through Faulkner's fingers as he fell.

"I always keep in mind that I am carving the largest piece of sculpture anyone ever attempted, a memorial that will stand through eternity," Faulkner told Neal all those years ago. "You could hardly ask for greater satisfaction than that."

Stone Mountain's carving was the only piece of art Faulkner ever attempted. After its completion, he worked as a corrections officer in DeKalb County, then in Florida. He tried his hand in the commercial fishing business, then returned to Georgia.

He opened his own short-lived museum to showcase his life's greatest work and, over time, fell ill.

—

Roy Faulkner died on Sept. 23.

He'd been feeling especially weak the week prior, and spent some time in the hospital. He'd been back at his daughter's home in Snellville for a few days when he aspirated and food went into his lungs. He went into respiratory failure and died at the hospital.

"It just happened so quickly," his daughter, Donna Faulkner Barron, said. "I was here all by myself."

Barron and her father spent the final year of his life promoting the 57-page, photo-heavy book she wrote about him. Appropriately titled "The Man Who Carved Stone Mountain," it was born of Barron's justified belief that her father had never been properly feted for his life's work, a fear that no one knew who he was.

And to some extent, the book helped correct that. After its publication, Barron's father appeared at several signings and recognition ceremonies, most of the latter tied to groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Before his death, he’d been scheduled to participate in Homeschool Day at Stone Mountain Park.

“I know Daddy probably wasn’t the happiest he could be,” Barron said, “but when we first released the book? Oh, the tears and happiness that came from his face.”

—

When the reporter’s visit is over, The Man Who Carved Stone Mountain gets up from his recliner and, with assistance, shuffles to a makeshift signing table set up across the living room. There are American flags and other patriotic decorations, and a five-foot vinyl sign advertising his daughter’s book stands tall over his right shoulder.

His daughter places a copy of the book in front of him and opens it to the title page. The man who made one of the world’s greatest artistic endeavors possible now battles with a Bic, slowly willing the pen to find the right fingers.

He scrawls a semi-legible version of his name on the page and smiles.

The reporter leaves and, later, sends an email to officials at Stone Mountain.

“The completion of the carving on Stone Mountain in 1970 can be attributed mainly to the talents and challenging work of Roy Faulkner,” they eventually respond. “While Faulkner was not a trained sculptor or artist, his contribution cannot be overstated in completing the carving which is the largest piece of artwork of its kind in the world.”

Visitation services for Roy Faulkner will be held from 5 to 8 p.m. Friday at Eternal Hills Funeral Home, 3594 Stone Mountain Highway in Snellville. A funeral will be held at the same location at 1 p.m. Saturday.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured