There is something about standing in the place where a historical event occurred that gives it weight. This is why we preserve historical sites, why tourists visit Civil War battlefields, and Graceland.

It was my wife who pointed out that I was very likely standing on the spot where my ancestor, Andrew Ross, and 19 other Cherokee leaders signed the treaty that gave away all Cherokee land that remained east of the Mississippi River.

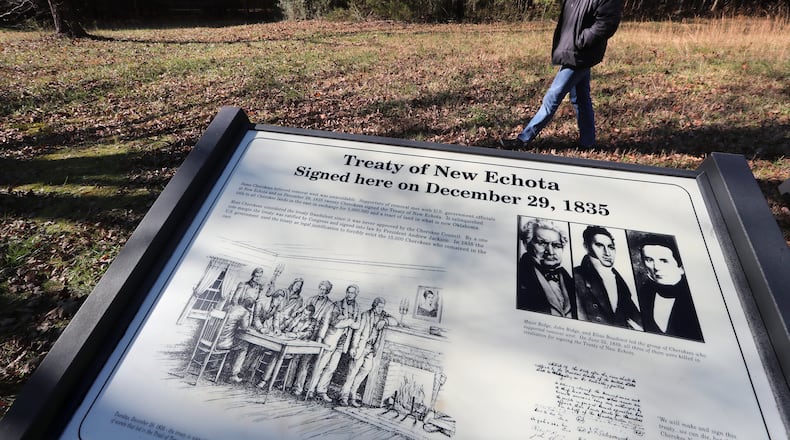

We were visiting the New Echota Cherokee Capitol State Historic Site near Calhoun on an unseasonably warm November day. The site was, for a short time in the 1820s and 1830s, the center of government for the Cherokee Nation.

The treaty was signed in the home of Elias Boudinot, who had been the first editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, the first newspaper published by a Native American tribe. All that remains of the house is a circular wall that once enclosed a well and the stone foundation of a kitchen. Four large stones now mark what once were the four corners of the house. I was standing in the middle of those stones.

When Andrew Ross, standing near that spot 185 years ago, applied his signature to that document, it sealed his fate. Nov. 29 was the 180th anniversary of his assassination during the struggle for power that erupted after the Cherokees arrived in Indian Territory, now northeastern Oklahoma.

I am a citizen of Cherokee Nation, born in Oklahoma, and I grew up learning the history of the removal: Georgia extending state jurisdiction into the Cherokee Nation and passing a series of laws meant to pressure Cherokees to leave; the Supreme Court case that declared Georgia actions illegal; the Andrew Jackson administration’s refusal to interfere in Georgia’s illegal actions; the treaty signed without consent of the elected Cherokee chief and council.

And then, most tragically, the roundup of Cherokee into stockades and the forced march to Indian Territory that killed thousands.

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

This was history I never encountered in any history class that I remember. It first came as oral tradition, from parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles. And those events always seemed far away, both in time and space: a family mythology, a legendary tale outside of history and context. That changed in 2008 when I moved to Georgia to take a job at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

I hadn’t thought of the move as a return to my ancestors’ homeland, so it came as a surprise when I was confronted with the real places of my family myth: New Echota, the John Ross House, Ross’s Landing, Trail of Tears National Historic Trail highway signs. Just across the state line in Fort Payne, Ala., Andrew Ross’s pre-removal home still stands, still a private home, the original two-story hewn-log structure buried under almost two centuries of expansions and renovations. It’s known today as Cherokee Plantation.

There is also Cherokee County, and Troup, Lumpkin and Gilmer counties named after Governors who were key to bringing about the removal, and Cherokee-derived names everywhere: Dahlonega, Cohuta, Chattooga, Currahee, Coosawatee, Amicolola, Coosa, Sautee, Enotah, Etowah, Ellijay, Tallulah. Georgia feels to me like a place haunted by ghosts that no one else sees. But the ghosts are no longer phantasms. Now I can touch them.

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

A reassessment of Indian removal

Recently, two wonderful books, one a newly-published history of the removal, another a history of modern memorials to the removal throughout the Southeast, have deepened my connection with this history and my understanding of how it connects with issues that still resonate in America.

“Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory,” by UGA history professor Claudio Saunt, was a 2020 National Book Award finalist and has found a place on several best books of 2020 lists, including the Washington Post and The Atlantic magazine. In it, Saunt argues that removal of the Southeastern native tribes was not a historical sidebar, but a critical event leading to the Civil War two decades later.

Saunt’s book demonstrates how Indian removal and slavery have much in common. Enormous profits were at stake in both cases. Both had the support of Southern planters backed by Northern financiers. Both faced an opposition in Congress that remained in the minority in part because of the constitutional compromise that allowed slaves to count in the census as three-fifths of a person, skewing representation. And both involved Southern threats of violent resistance to federal authority.

Credit: Andrew Zawacki

Credit: Andrew Zawacki

Twenty years before the Civil War, large swaths of Alabama and Mississippi, and 10 years before that, much of Georgia was controlled by Native American nations. The Creek, Choctaw and Chickasaw nations sat on what has been called the “Black Prairie,” possibly the most valuable farmland in the world at the time.

By the Civil War, those former Indian lands were occupied by almost a quarter million slaves working on cotton plantations developed with financing from Northern investors. In 1850, this land generated 160 million pounds of ginned cotton and 40% of the entire agricultural output of Alabama and Mississippi.

“So, the transformation that the South undergoes in just this really short time span is really extraordinary. And it hinges on the deportation of native Americans, the expansion of the cotton production and slavery across the South,” Saunt said in a recent interview.

The only original structure that remains at New Echota today is the home of the missionary Samuel Worcester. He and three other missionaries were arrested, convicted and sentenced to hard labor for refusing to ask Georgia’s permission to remain in the Cherokee Nation. His conviction was subject of the U.S. Supreme Court case, Worcester v. Georgia.

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

The court ruled that Georgia laws had no power inside a sovereign Indian nation. Inconveniently for Andrew Jackson, the ruling came in the middle of the South Carolina nullification crisis, when the South Carolina legislature declared a federal tariff unconstitutional and asserting its right to nullify any federal law within its borders. The Worcester ruling further fanned nullification feelings across the South, fueling fear that a fusion of the two issues could lead to disunion.

After Worcester, Governor Wilson Lumpkin pardoned the missionaries and their mission board urged them to accept it. This sidestepped a direct federal confrontation with Georgia while leaving the rest of Georgia’s harassment laws intact. It also kept Georgia and the other the Southern states that wanted to rid themselves of their Indians from joining South Carolina’s nullification movement.

But the short-term gain of isolating South Carolina in its protest over federal tariffs emboldened Southern resistance to Federal policy in the long run.

“I call it the war the slaveholders won,” Saunt said. “They are making these threats and, in the end, the federal government backs down. There’s a lot of bluster, and then they get their way. There’s a lot of bluster in the 1850s too, but in the end they don’t get their way and they do end up having to go to war.”

A political fight narrowly lost

The removal is usually characterized as inevitable, history taking its course. Supporters of removal argued at the time, sometimes cynically, that it was the only way for the Indians to save their culture from corruption by Europeans. More recently the moral polarity has been reversed: it was the inevitable result of settlers’ avarice for land.

But Saunt argues that removal was far from inevitable. Removal faced strong opposition. It generated the first mass petition campaign to Congress, much of it organized by Northern women who would later turn their organizing efforts to the abolitionist movement.

“When you read through the petitions, the language that they’re using is really heartfelt. They believe that the very fate of the Republic rests on what is going to happen in the 1830s,” Saunt said. “They fervently believe that the United States represented this other possibility in contrast to the corrupt despotic governments in Europe. The United States was going to represent something different.”

Credit: special

Credit: special

Native leaders also mounted a sophisticated political defense, adapting the Republican language of their northern supporters to their cause. Tribal representatives maintained a constant presence in Washington and the Cherokee Nation newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, had sharing agreements with newspapers which republished the Cherokee perspective throughout the North.

Removal policies passed Congress by razor thin margins, and Saunt could easily imagine a scenario where the tribes were able to maintain some presence in the East. This, he said, would have resulted in a very different relationship between European Americans and Native people.

Another revelation in Saunt’s book is the shear scope of the removal operation. Saunt points out the irony that Southern leaders challenged federal authority during their campaign for removal, but also depended on the federal government as the only entity capable of carrying it out.

Saunt characterizes the mass expulsion of Native people from the Southeast as the largest bureaucratic operation yet undertaken by the still young nation. He estimates the cost of removal at $75 million, a trillion dollars in current dollars or $112 million per deportee. In the years between 1830 and 1838, the removal efforts accounted for as much as 40% of the annual federal budget.

The expenses were meticulously recorded, down to the 1836 receipt to William Spickernagle in Memphis, Tenn., for building two coffins and digging two graves for an Indian man and woman, $10.

Saunt is associate director of the Institute for Native American Studies at the University of Georgia, and I was curious how such an institute came to be in a state that has no federally recognized tribes and few Native people?

“I live two blocks from Lumpkin street”, he said. “And the University of Georgia sits on (Gov. Wilson) Lumpkin’s plantation. Actually, all of South campus is Lumpkin’s plantation and his house is there on South campus. He probably, more than anyone, drove this cause. And it just makes sense for Georgia to be a leader in this area.”

Contradictory commemoration in the South

If Native history was largely absent from the American history I learned in school, modern Indians are entirely absent.

As Western Carolina University professor Andrew Denson points out in his 2017 book, “Monuments to Absence: Cherokee Removal and the Contest over Southern Memory,” the many removal memorial sites scattered throughout the Southeast, as the name of his book implies, are monuments to people who have disappeared from the landscape and from history. The memorials are telling narratives of replacement.

“Embracing certain elements of the Native American past, if anything, deepened the possession of Southern places by Southern communities,” he said in an interview.

In the book’s introduction, Denson described how the idea for his book grew from a visit to New Echota more than two decades ago. When Denson was in graduate school at Indiana University in 1994, he and a friend, during a break in classes, took a road trip to Florida. Passing through Georgia, he saw a road sign for New Echota. The history of Cherokee sovereignty and nationhood had become a focus of his research, and he’d just taken a class that looked at public memory of historical events. He couldn’t pass the sign by.

Looking around, Denson guessed that the New Echota site had been built in the 1980s. He was surprised to learn that it had opened in 1962. In the midst of Southern resistance to desegregation and to the Black civil rights movement, Georgia had built a memorial to a previous blight on the state’s history, the forced deportation of 20,000 Cherokees on the Trail of Tears. The encounter became the seed for his book.

“The question I’m trying to explore in it is why are Southern communities, predominantly white Southern communities, so interested in this story? What are they doing with it at different times of their history,” Denson said.

Credit: Photo by Mark Haskett

Credit: Photo by Mark Haskett

In his book, Denson explains that removal memorials began to appear with the growth of tourism in the Southern Appalachians sparked by development of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the 1920s. It continued through the 2000s with creation of the U.S. Park Service’s Trail of Tears National Historic Trail and the growth of Trail of Tears Association chapters in states and local communities along the multiple paths of the trail.

Planning for the New Echota site began in the 1950s as a project of the Calhoun Chamber of Commerce. The project was eventually adopted by the Georgia Historical Commission and opened as a state historical site in the spring of 1962. In anticipation of that opening, the Georgia Assembly voted unanimously that February to repeal many of the Cherokee harassment laws that remained in the Georgia statutes from the 1820s and 1830s.

“In doing this,” the bill said, “Georgia atones for the wrongs done to these worthy people.”

A few days before that vote, students from Atlanta’s Black universities had been expelled from the Capitol after attempting to desegregate the Georgia Assembly public galleries. During the vote to repeal the anti-Cherokee laws, and while legislators were making speeches apologizing for the state’s past wrongs against Native people, the students were outside protesting the segregated galleries.

Columnist Celestine Sibley wrote the next day in The Atlanta Constitution, “One of the nice little ironies observed in the Capitol the other day was that while Rep. Charles Pannell spoke movingly of a bill to make Georgia safe for Indians, a phalanx of state troopers assembled on the front sidewalk to require a picket line of negro students keep their distance.”

New Echota was part of a wave of Cherokee removal memorial construction throughout the South in the 1950s and 1960s. Part of the motivation was commercial, an attempt to capitalize on the increase in automobile tourism after World War II. The ambition for New Echota was to become a Native American Williamsburg.

But Denson argues that there were also symbolic meanings and implied moral lessons in the memorials. The first was admiration for the Cherokee people and their success in becoming “civilized.” This had been a major theme in all removal commemorations since the 1920s at least.

Credit: special

Credit: special

A second theme was new to commemorations of the 1950s and 1960s, a time when Southern states were pledging maximum resistance to federal desegregation laws: atonement for their previous defiance of federal law that contributed to Indian removal.

“The same people who are engaged in a lost cause commemoration, the Jim Crow era Confederate commemoration, they are some of the same institutions and same groups that eagerly embrace certain elements of Cherokee history, and they don’t see that as contradictory,” Denson said.

Denson’s book argues that it was a safe way for Southerners to declare their allegiance to American civic ideals of democracy and equality without challenging existing policies of white supremacy. The Indians were gone and an apology, now, posed no political challenge. African Americans, however, remained.

“It can be empowering, I think, to apologize in these ways or to recognize oppression in ways that don’t necessarily require a political action in the present in the way that, in the 1960s in Georgia, acknowledging slavery as an oppressive system has known implications for the politics,” Denson said.

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

An historical site ready for visitors

The New Echota Historical Site never reached the status of Williamsburg, which attracts more than a million visitors annually. About 10,000 people visit New Echota in a normal year, said interpretive ranger Bobby James. School field trips account for about half of those visits, he said.

When I visited, on a weekday during a pandemic, there was a steady trickle of visitors. Most of the original buildings at New Echota were destroyed after removal. The only original building that remains is the home of Samuel Worcester, the missionary arrested by Georgia and whose case before the U.S. Supreme Court remains a foundation of Indian law today.

The national council building, supreme court building and Cherokee Phoenix printing office have been recreated from historical records. Period buildings were relocated to the site to represent typical and middle-class Cherokee farmsteads at the time. A tavern built by Cherokee planter James Vann was also moved to New Echota from its original site at a Chattahoochee River crossing to represent the tavern that once existed there.

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

Credit: Curtis Compton / Curtis.Compton@

Recordings and interpretive signs scattered along a path leading through all these features provide not only a history of the site, but also information about Cherokee language and culture. They also provide details, missing from many removal memorials, about the three modern Cherokee tribes: the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in Cherokee, N.C.; and in Oklahoma the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians and the Cherokee Nation, now the largest federally recognized Native nation with 360,000 citizens and an annual budget of $1.5 billion.

There is a small museum, a theater where visitors can watch a short video history of the site, as well as nature trails and an outdoor picnic area. The site at 1211 Chatsworth Highway 225, Calhoun, Ga., is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, and from March through November from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays.

I recommend a visit.

John Perry is technical director of the data team at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured