Winters are always busy at health care facilities. This year, in addition to a super contagious coronavirus, hospitals have been dealing with a more ferocious flu season, other respiratory viruses and fewer available hospital beds in Atlanta. Health reporter Helena Oliviero recently got a close-up view of the confluence of all these factors.

Susan Oliviero’s green eyes squint under fluorescent lighting in the crowded emergency room. She’s nearing 10 hours in a waiting area at Emory University Hospital’s sprawling main campus.

She shakes her head. She can’t believe how much her body hurts. The worst, she says, is her throat. “It feels like it’s on fire,” she mouths. She can barely swallow without gagging.

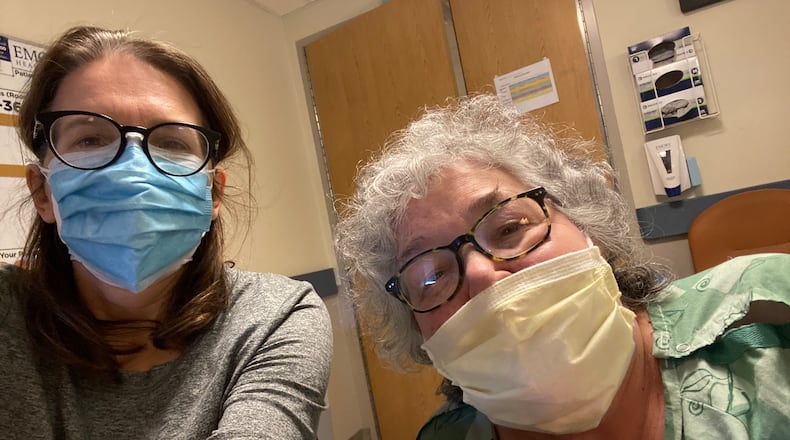

After nearly three years of avoiding the virus, Oliviero, my mother, had tested positive for COVID-19 just a few days earlier.

So, there we sat, on her 81st birthday. Instead of eating chocolate cake, opening presents and taking phone calls from family and friends, we were at the ER along with a line of others battling COVID as well as a host of other illnesses and injuries.

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Georgia is slogging through yet another winter with the virus circulating among us. The latest official count of COVID cases, released Wednesday, showed a 71% jump since at the start of November. Older Americans and emergency rooms once again are bearing the brunt of the hit, even with the number of infections decreasing in recent weeks.

Gone from area hospitals are the medical trailers, the beds in hallways and the line of ambulances out front. But the local health care system is still feeling the strain.

The newest iteration of the virus is the most easily transmissible yet, and it comes as other seasonal illnesses, like the flu and Respiratory Syncytial Virus, or RSV, linger. Compounding the problem, Atlanta lost 460 hospital beds and a level 1 trauma center with the closing of Wellstar’s Atlanta Medical Center in November.

A reporter covering the pandemic for three years, I had a chance to see the convergence of all of these elements — a super contagious virus inside a vulnerable body inside an overburdened health care system — when my mother fell ill in mid-January.

I’ve written more than 300 stories about the virus, but my mom’s bout of COVID reiterated to me how unpredictable the disease can be. Early intervention was likely key to her good outcome. Her illness and long, uncomfortable wait in the emergency room also gave us ample time to observe one hospital staff working to manage the recent increase in patient volume.

COVID is not the same threat that it once was. Because so many people have been vaccinated or infected or both, the number of Georgians whose immune systems are completely unprepared for the virus has fallen significantly.

But I know my mom is part of a demographic most at risk of severe illness from COVID. The virus poses a particular danger to adults 65 and older, even those who are vaccinated. Right now, nearly 9 out of 10 COVID deaths in the U.S. are in that age group. And she is a former smoker with high blood pressure, factors that can contribute to complications.

My mother arrived from Vermont on a Thursday. By Saturday, she had a runny nose and her eyes were watering. She didn’t say anything because she wasn’t concerned. She chalked it up to fatigue from travel.

By Monday, she was congested and felt bad. That morning, when I walked into the room where she was, she said, “Stand back. I think I have a cold.” I immediately reached for a COVID home test. Perhaps we shouldn’t have been, but we were surprised by the result. She was current on all of her COVID vaccinations and usually careful, wearing masks and avoiding crowds as best she could.

I called her doctor in Vermont to get a prescription for the antiviral Paxlovid. The drug is a key weapon in preventing serious illness, but it must be taken within five days of the onset of symptoms. It helped me to quickly feel better during my case of COVID in October.

Gone from area hospitals are the medical trailers, the beds in hallways and the line of ambulances out front. But the local health care system is still feeling the strain.

My mom’s symptoms, too, were better the next day. She was even hungry. We thought, as did her primary care doctor, that she was on the road to recovery. Then, her condition suddenly worsened.

She started to feel weak again, developed a severe sore throat, and her congestion was becoming more of a concern. The quick reversal, frankly, scared me. Like many COVID-conscious Americans, I now have a pulse oximeter at home. That’s a device that clips onto your finger and allows you to see how much oxygen saturation is in your red blood cells. In other words, it tells you how efficiently your lungs are working. Above 95% is considered normal. My mom’s had dropped into the 80s that Thursday — and didn’t improve.

While the number of COVID deaths has fallen significantly, about 100 people are still dying of COVID every week in Georgia, according to data from the state Department of Public Health.

At 9 p.m., I knew it was time to go to the emergency room.

Fallout from Wellstar AMC closure

Patients at an emergency room are seen based on the severity of illness, not the order of arrival. I asked a receptionist for a ballpark on how long it might take for her to be seen by a doctor, and she told me evening wait times were averaging close to 15 hours. I thought she might be exaggerating. She wasn’t.

Shortly after we arrived, the staff did an initial assessment, and my mother was hooked up to an oxygen tank. Then she was sent back in a wheelchair to a large waiting area outside the emergency room, wearing a surgical mask over the oxygen mask.

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Later, blood was drawn, and an X-ray was performed on her chest. Then, again, she was wheeled back to the waiting room. The oxygen helped. But she felt excruciating pain, now stretching from her throat to her ears.

As the hours ticked by, we witnessed a hospital system struggling to provide timely care during a winter-time rush of patients.

The situation in metro Atlanta is especially acute. Most local emergency rooms ran above capacity before Wellstar Atlanta Medical Center’s closure. Emory is among the hospitals forced to absorb the fallout, which includes everything from broken bones and cuts to wound infections and COVID.

A hospital spokeswoman said Emory Healthcare’s six emergency rooms have seen a 35% increase in the number of ambulances arriving since Wellstar AMC closed.

As the darkness of night gave way to morning light, an Emory staffer approached me in the waiting room. She apologized for the wait. The issue at that moment wasn’t that the hospital didn’t have a bed available. It didn’t have a nurse available.

The demands and stress on health care workers who have been on the frontline of our country’s fight against COVID have been intense. Hospitals are facing staffing challenges of epic proportions.

Around 9 a.m., about 12 hours after we checked in, a doctor stepped inside the waiting area. I was sitting a few feet away, double-masked. My mom and I were dozing off when he jolted us awake.

“Susan Oliviero!”

Giving grace to health care workers

Once we got into a small treatment unit in the emergency room, a nurse told us to get comfortable — my mother might not be moved into a regular hospital room for a long time, maybe 20 hours.

My mom couldn’t leave the tiny unit with a glass door because she was COVID-positive. There was no bathroom, but the little room had a portable toilet — with a missing seat.

We quickly realized we had to pick our spots. I wanted to give the health care workers grace. I realize they’ve been battered with wave after wave of COVID. And now I saw how feverishly they were working. We decided not to call the nurse for blankets. I already had been told they were out of pillows.

Still, after a couple of hours with no fluids or medication to ease my mom’s pain, I had to speak up. Was there a reason they were holding off on IV fluids? I was concerned because she had gone nearly 24 hours with only a few sips of water. Not to mention my mom was in agony.

About three hours after we were put in the little glass room —15 hours after coming to the emergency room — my mom started getting intravenous fluids and remdesivir, another antiviral. And while it wasn’t easy, she swallowed a dose of lidocaine viscous, a local anesthetic that numbs the mouth and throat.

The pain in my mom’s throat eased immediately.

Despite the wait, once it was my mom’s turn, I felt good about the care she received. While the nurses seemed to be working as fast as they possibly could, the care inside that tiny room didn’t feel rushed in any way.

Then Dr. Elbert Chun, the Emory hospitalist in charge of my mother’s care, entered the room in a yellow isolation gown, mask and face shield.

While we had been a bit taken aback that my mom had gotten COVID, given all her precautions, Chun didn’t seem surprised at all — the latest strain is ultra-contagious. But this variant tends to cause less severe illness than earlier strains. I not only felt like my mom was in expert hands, Chun possessed a great bedside manner. He connected with my mom by asking her about the foliage in Vermont — seamlessly making pleasant conversation while also reviewing her test results.

“I had this gut feeling, that despite her low oxygen levels, I was very optimistic for her,” he would say later.

There were no signs of COVID pneumonia. She didn’t have blood clots. And, with each drop from her IV, she seemed to be getting better already. As I watched the beeping machines, I saw her oxygen levels rising back into the 90s.

I saw how feverishly the nurses were working. We decided not to call them for blankets. I already had been told they were out of pillows.

We dimmed the lights, and my mom fell asleep. And I slipped out the door to go home for much-needed rest.

There is no good time for getting COVID. But my mom’s timing could have been much worse.

Early in the pandemic, when doctors were facing a crush of patients stricken with a new mysterious virus, Chun said it was “nerve-wracking.” Complications from heart attacks, strokes, pulmonary embolisms were more common.

The delta variant, which became the dominant variant in the summer of 2021, was “very, very harsh,” Chun said.

And “omicron is still worrisome,” he said. “But, anecdotally, I haven’t had to send patients to the ICU at such a high frequency, fortunately.”

Now, he said, “We feel very confident we’ll be able to turn things around. But we’ve got to be careful. Not everyone’s the same. We still have to be cautious, and a few months ago, we probably let our guard down.”

Antivirals probably prevented ICU stay

By the next morning, my mom was in a regular room in the hospital. Her sore throat was gone. She was sitting up and cheerful. Her cheeks were rosy, her eyes more relaxed. She was back to her chatty self, talking about books and movies and discussing a recipe for blackberry syrup.

When Dr. Chun visited my mom again, he seemed pleased with her improvements, though he described them as “pretty OK, not perfect.”

Steroids likely helped keep my mom out of the ICU, according to Chun. That, combined with the antiviral treatments, “probably had the biggest effect on her great outcome,” he said.

Other factors in her favor: being fully vaccinated, which includes the updated bivalent booster, he said. The booster targets the original coronavirus strain as well as omicron subvariants.

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Though it’s unclear whether it’s any more effective than earlier boosters against the predominant XBB.1.5 subvariant, many doctors say it’s still important for people to get the injection. Staying up to date on vaccines and boosters helps a body to maintain protection against the virus.

For many, however, COVID weariness has set in. More than two-thirds of older Georgians have not gotten the bivalent shot.

Chun said getting tested as soon as you feel symptoms and getting antivirals as soon as possible is critical. “Don’t wait it out,” he cautioned.

After a few more tests, and another round of antiviral medications, he decided it was OK to release my mom to go home.

“You did everything right,” he told my mom. “And, unfortunately, you still went through this. On the flip side, it can be worse.”

Back at home, my mom was no longer in pain, and she quickly settled back into a routine.

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Credit: Helena Oliviero

Over the next few days, she continued to improve. We celebrated her birthday with cake and gifts, and everything seemed sweeter.

Though mild symptoms returned for a little while, which isn’t uncommon if you take Paxlovid, she was able to weather them better.

When my mom reflected on her hospital stay, she said it seemed chaotic at first. But, she said, she knows the nurses and doctors were putting together a thorough plan to help her get better.

“I feel very grateful,” she said.

Me, too, mom. Me, too.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured