An adamant Danyel Smith insisted he had not shaken his 2-month-old son Chandler so violently it ultimately caused the infant’s death.

“If I knew what happened to Chandler I would tell the jury,” Smith testified at his 2003 trial in Gwinnett County. “If I shook my son, I would say I shook my son. But I didn’t do that.”

Jurors didn’t believe him. They convicted Smith of murder and he was sentenced to life in prison.

Now, 18 years later, Smith’s lawyers contend he was wrongly convicted. With help from an eminent pediatric neurologist, they say Chandler’s death on May 6, 2002, was not caused by shaking — he died of natural causes.

Advancements in medical diagnostics not available in 2002 show that complications from Chandler’s premature birth and subsequent seizures contributed to his death, Smith’s lawyers say in an extraordinary motion for new trial.

“Today, we know that the death of Chandler Smith was a tragedy, but not a crime,” the motion said.

“With today’s science now confirming Mr. Smith’s innocence, we hope that the district attorney will act quickly to correct this miscarriage of justice,” said Smith’s attorney, Mark Loudon-Brown of the Southern Center for Human Rights.

Gwinnett District Attorney Patsy Austin-Gatson said her appellate attorneys are aware of the motion.

“If it turns out that it’s a motion that is substantiated, we will certainly give it a thorough review,” she said.

The National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome estimates there are about 1,300 shaken baby — also called abusive head trauma — cases a year. About 25 percent result in death, while 80 percent of the survivors suffer lifelong disabilities.

Over the past decade, however, a number of medical experts and legal scholars have called into question the diagnoses used years ago to help convict people of shaken baby deaths. The National Registry of Exonerations lists 19 people who have been cleared.

“There’s no question there are more out there,” said Keith Findley, a University of Wisconsin law professor who has written extensively on the subject. “The question is: How many and how do we find them?”

In their motion, Smith’s lawyers said they found one.

Their case is supported by Dr. Saadi Ghatan, the director of pediatric neurosurgery at Mount Sinai Health System in New York.

“Chandler’s death was not the result of parental abuse or mistreatment, nor was his death caused by anyone,” Ghatan said in a sworn affidavit. “Rather, the events surrounding his untimely death at 2 months of age began with his early and difficult birth.”

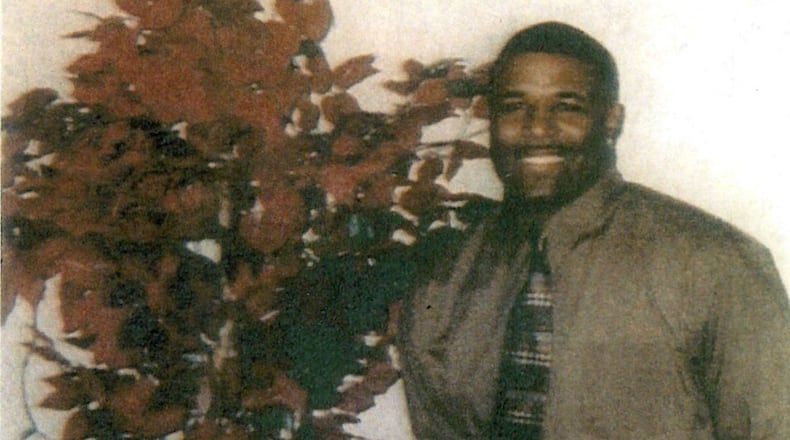

Ghatan noted that he set out to review the case with a clear understanding that Chandler’s death may have been caused by Danyel Smith, who is now 45. Ghatan said conducted the review on his own time and at his own cost.

In 2002, Smith was living in Norcross with Marsha Collins, who was pregnant with Chandler. They had met the previous year at the Vegas Nights club in Marietta, and Smith moved in with Collins after being laid off as an account manager at Equifax.

Six months into her pregnancy, Collins, then 38, was in a car accident. Leading up to Chandler’s birth, she took time off from her job at the Parisian department store and was repeatedly taken to the hospital with uterine contractions, court records said.

When doctors noticed the baby was not growing properly, they induced premature labor. After 33 hours, Chandler had not moved down the birth canal and was showing signs of distress, so an emergency C-section was performed. The 4-pound, 10-ounce baby was born Feb. 27, 2002.

A week later, Chandler was allowed to go home. Before he left, he was given immunization shots, including two Hepatitis B vaccines, one more than necessary, court records said.

Almost two months later, on April 29, 2002, Collins and Smith took Chandler to his pediatrician for a checkup. At the end of the visit, Chandler was given shots, including another Hepatitis B vaccine, according to court records.

At trial, Collins testified that Chandler cried and screamed after getting the shots. But after she fed him, he fell asleep.

On the way home, Collins told Smith he needed to find another place to live, which upset him, she testified. After dropping off Smith and Chandler, Collins left to apply for WIC public assistance. But when she got to the office, she was told she had to have her baby with her.

Collins called Smith and told him to bring Chandler. After complaining that only Collins’ car had an infant seat that fit Chandler, Smith drove off holding Chandler in his arms.

When he was at a red light, Smith testified, he looked down at his son and saw something was wrong and when he checked for a pulse, he found none. So he pulled over, put Chandler on the top of the trunk and performed CPR. After he got a pulse, Smith testified, he drove to the WIC office.

When he pulled up, Collins called 911 after seeing Chandler’s limp body. People from inside the office tried to resuscitate Chandler until EMTs arrived. Chandler was taken to Scottish Rite Children’s Hospital, where he was taken off life support a week later.

In an interview, Collins said she continues to believe Smith is guilty.

“That’s not true,” she said of the new trial motion. “I don’t believe it at all.”

An autopsy found that Chandler had a skull fracture above his left ear, small wrist fractures, retinal hemorrhaging and a subdural hematoma — a pool of blood between his brain and its outermost covering. With no other explanation for this trauma, such as a car accident, Medical Examiner Steve Dunton determined the young child died from intentional, abusive shaking.

Smith, the last person with Chandler, was indicted for murder.

At trial, Dunton delivered devastating testimony. “We have a collection of findings here that are classic and in some cases virtually exclusive for violent shaking,” he said.

Pediatric neurologist William Boydston, who treated Chandler at Scottish Rite, agreed that the baby had all the traumas associated with being shaken.

“Unless somebody could tell me something else was going on with the child,” Boydston testified. “You know, I think he was a shaken baby. I’ll be happy if somebody can tell me something else.”

Smith’s lawyers say they now know something else was going on with Chandler.

Chandler’s delivery via C-section was carried out by vacuum removal in which doctors applied suction and pulled on the baby’s head to remove him. The procedure likely caused Chandler’s skull fracture, Ghatan said, noting members of the medical team noticed swelling in the newborn’s head shortly after birth.

Back in 2002, neither a CT-scan nor an x-ray were performed, and appropriately so, because it could have exposed Chandler’s young brain to radiation, Ghatan said. But if ultrasound technology had been available, it could have detected the fracture, he said.

“We routinely document a much higher frequency of skull fractures in infants due to birth and incidental traumas than was done so two decades ago,” the neurosurgeon said.

Moreover, Chandler’s skull fracture was not new, so it could not have occurred on the day he became unresponsive, Ghatan said. “(I)t very likely dated back to his birth.”

The scans taken after Chandler’s birth show bleeding on the brain, which can cause seizures, Ghatan said. He also noted that when Chandler was about a month old, Collins called 911 because she was concerned he was having seizures.

It is possible that Chandler’s third Hepatitis B vaccine during the checkup triggered brain seizures, which could have caused him to stop breathing, Ghatan said.

The neurosurgeon said he based his diagnosis on the availability of neonatal and infant imaging that was unavailable in 2002 and the knowledge that vaccinations cause adverse reactions, such as seizures. These perspectives, he said, “allow us to see that Chandler’s death was not caused by an individual.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured