Understanding the generation gap within the LGBTQ community

During Pride Month, generations within the LGBT community are continuing conversations about what is important to gay youth versus those who remember the Stonewall riots and those who survived the AIDS crisis. Differences between generations — perceived or real — have existed long before the term “generation gap” became popular in the 1960s. The generations often have different views on social, political, pop culture and religious issues, and while these differences are universal, they are also played out within groups.

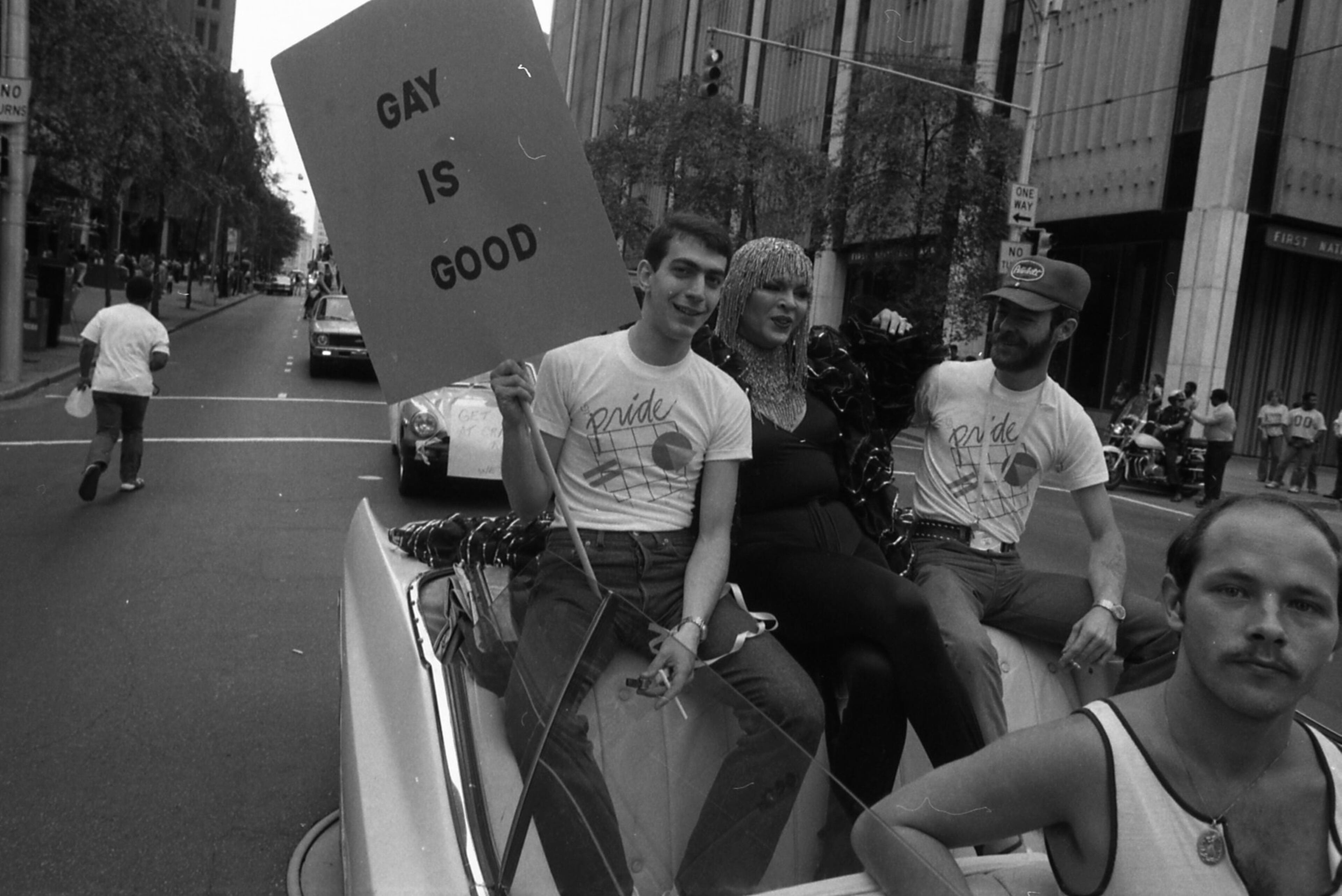

The Gay Rights movement traces its beginning to 1969 when New York City police stormed the Stonewall Inn, a Greenwich Village gay bar, and rather than pacifically be arrested, the bar’s patrons, led by black transgender women, fought back. The first Pride parades started the next year — 50 years ago. In 1971 Atlanta held its first Gay Pride parade with about 100 participants (and no city permit). Today, Atlanta’s Pride parade takes place in October and is one of the country’s largest celebrations; in 1996, the Black Pride Parade debuted, also in October.

Errol "E.R." Anderson, executive director of Charis Circle, a nonprofit aimed at fostering sustainable feminist communities, offers a perspective. "I see 18-year-olds sitting next to people in their 60s sharing tactics with one another. We need for all generations to talk about what's going on and apply our wisdom and political analysis," he says. "Each movement is built on the other."

The older generation thought they could change the world, and they really felt there was no going back, says Anderson. “I’m not sure the baby boomers have resentment over the younger generation because, let’s face it, they still hold the power. It’s more frustration at not being able to hand down a revolution that was sustainable.”

» RELATED: June is LGBT Pride Month — when is Pride in Atlanta?

Derek Baugh, a 28-year-old transgender man in Atlanta, agrees — somewhat. “Every group has its own issues, but sometimes it feels as if the older generation doesn’t believe our issues or experiences,” he says. “They tell us that we don’t know how hard they had it coming up. We’re not supposed to know how hard it was. We’ll never know what they went through. They went through it, so we don’t have to. We know that — and thank you. We have our issues that we’re passionate about.”

Two factors define the generations — creating a community and AIDS. LGBT baby boomers were mostly in the closet afraid of being outed, losing their jobs and families, possibly their lives — and, often tried to maintain an aura of respectability via being married and having children. "There were people who never were able to come out," says Nasheedah Muhammad, 45, co-executive director of Lost-n-Found Youth, a nonprofit that addresses issues of homelessness. "It wasn't even on their radar."

Generation X found strength in numbers. “We were the support group generation. We went to youth groups at the Atlanta Gay and Lesbian Center. That’s how we built our community,” says Muhammad.

Today’s gay youth are connected no matter where they live. They are more integrated into the mainstream and find it easier to navigate their sexuality within society, says Muhammad. “Things are still hard, but it’s hard in different ways,” she says.

The internet has changed everything for younger people, says Anderson. Today, younger gay men and women easily can connect with others like them. “I’m the bridge generation where we met people in bookstores, bars and meetings and feel grateful for that,” he says. “But it also can be hard for younger people. Try being the only gay person in your small town, going on the internet and measuring yourself up against a lot of people. It can bring on self-esteem issues, and we’ve not dealt with that.”

» RELATED VIDEO: 5 LGBTQ facts

Some believe, for the younger generation, safety issues are not foremost on their minds. “They didn’t have to fight for the right to exist,” says Dr. Katie Acosta, associate professor of sociology and an affiliate faculty member for women and gender sexuality studies at Georgia State University. “I don’t want to say that the younger generation hasn’t had to fight for their rights, but they kind of pushed themselves in a different direction. That is where the gap is with this younger generation.”

Paul Conroy, founder and producing artistic director of the Out Front Theatre, adds that young people still wrestle with prejudice and living in the closet. “That’s not to say that there aren’t younger people still experiencing that prejudice of not living their true selves, but they aren’t going to have to replay “Don’t ask, don’t tell” or marriage equality. They have other issues.”

The AIDS crisis was another defining time. AIDS has killed more than 700,000 people since 1981, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Anderson says there is a “huge generational gap” between those who survived the AIDS and those who came after. “To live without that fear is really revolutionary, even in COVID times. There are definitely generation differences,” he says.

Conroy worries about the recklessness of youth. “I feel youth, in general, have an air of invincibility. Especially now with HIV affecting so many people and with so many gay men on prep (AZT, a drug that slows down or stops the virus’ growth), I fear younger men are just ignoring the health recommendations about AIDS and even with this pan-demic. It’s really hard for older generations who saw their friends being just wiped away to see this.”

“HIV is absolutely a problem, and black trans women are disproportionately affected,” says Baugh. “Concern for people with HIV should be paramount. I want to know why people living with HIV and AIDS are going without housing or access to services.”

Adding, “People say look how far we’ve come; I say look how far we have to go.”

Issues under the rainbow flag

As the world changes and progress is made, the issues confronting generations have changed, although some still remain. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled Monday the Civil Rights Act of 1964 applies to discrimination in the workplace against people who are LGBT. Concerns within the gay community include inequities regarding marriage, homelessness and how others describe, reference and label the LGBT community.

Marriage

On June 26, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all bans on same-sex marriage, legalizing it nationwide. Five years earlier Kirsten Ott Palladino co-founded Equally Wed, an Atlanta-based online wedding magazine, book and education resource for LGBT couples.

“For today’s generation, getting married isn’t an issue. I’m not sure they understand how hard it was before,” she says. “We have people getting married at 22. Whereas we’ve featured octogenarians who have been together 50 years waiting for this moment.”

That gap may foster some jealousy among Boomers, Conroy adds. “It’s heartbreaking to see older people who have been with their partners for decades and never were able to be legally married because their partner passed away. Today you can get married, go on a honeymoon, have kids. Younger people take that for granted. Older people may be a bit jealous.”

Homelessness

About 40 percent of all homeless youth are gay, according to a study by the Williams Institute at UCLA Law. A 2018 study by Georgia State University and Atlanta Youth Count found that nearly 44 percent of LGBT youth experience trafficking in comparison to 35 percent of their straight peers while homeless.

» RELATED: Thomas Roberts starts Facebook Live “Gay Good News” show

Lost-n-Found works closely with homeless youth. Particularly affected by homelessness is the transgender population. "Housing is a major concern for people with HIV and who are trans," Baugh says. "This is a very vulnerable population." Adding to the situation is the lack of health care, again with the trans population being more affected. "There is a lack of health providers who know about the issues facing the trans population," he adds.

Labels

Words are another sticking point. “It involves the terminology used to describe themselves,” says Acosta. “The younger people are using the word ‘queer’ to reclaim a once derogatory term. The older generation struggles with that because, for them, that word often involved physical threats and violence.”

And the beat goes on

Jeff Graham, 55, is the executive director of Georgia Equality, a local organization that aims to advance fairness, safety and opportunity for LGBT communities. Graham moved to Georgia 31 years ago when the then-state attorney general Mike Bowers was defending sodomy laws. “I couldn’t believe the court was rejecting my humanity and actually had an interest in my sexuality,” he says. “Fast forward and the debates about our rights are still ongoing.”

In 2015, Georgia Equality hired Bowers to fight two religious liberty bills facing the legislature. “It just shows that if you stay engaged and live long enough things can change. No matter how bad it can seem, it’s not trite to say that it does get better,” he says. “You have to meet people where they are and give them space to open there hearts and minds. It’s a privilege to see that work time and time again.”