Muhammad Ali’s return to the ring electrified Atlanta, black community

During the month of February, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution will publish a daily feature highlighting African American contributions to our state and nation. This is the fifth year of the AJC Sepia Black History Month series. In addition to the daily feature, the AJC also will publish deeper examinations of contemporary African American life each Sunday.

It was October 1970 and the former heavyweight champion of the world hadn’t fought in three and a half years.

America was divided as ever as the Vietnam War raged overseas and young men were drafted to fight — and often die — right out of high school.

Stripped of his title at the height of his career and banned from the ring for refusing to join the war after being drafted, an undefeated Muhammad Ali made his return to boxing in Atlanta as the world looked on.

In the summer of 1967, Ali had been convicted of violating Selective Service laws after famously declaring, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” Ali asked.

RELATED VIDEO: Ali-Quarry: Full fight

As he appealed his conviction, he was stripped of his title and his license to fight by all the major boxing commissions in the U.S.

More than 50 locales denied him a chance to return to the sport — until one Southern city that had developed a reputation as the “cradle of the civil rights movement” offered him another chance.

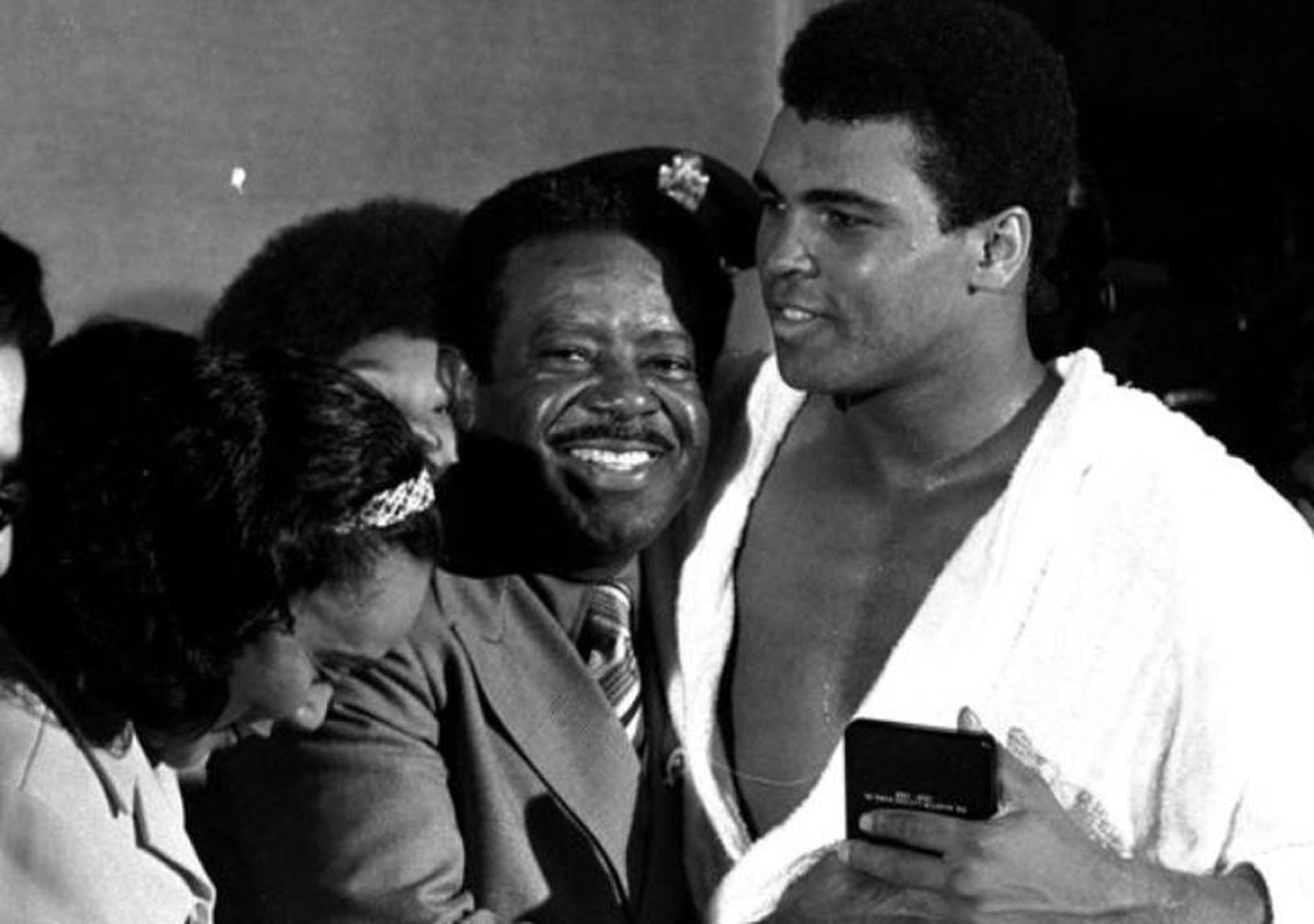

Atlanta was the only major city willing to host Ali’s return, and the atmosphere surrounding his comeback fight against Jerry Quarry was electric, said four-time world heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield.

»RELATED: The Louisville Lip: Muhammad Ali’s fighting words fueled a movement

At the time, Holyfield was just 8 years old. The youngest of nine children growing up in Atlanta’s Summerhill neighborhood, he remembers the buzz surrounding the fight.

“It was a big atmosphere and it was all anyone was talking about,” he recalled. “That was it.”

In the years leading up to the fight, Ali had developed a reputation as America’s most outspoken athlete.

Never one to shy away from controversy, “The Louisville Lip” was revered by the nation’s civil rights leaders, and his opposition to the Vietnam War helped cement his position as a counterculture icon.

»RELATED: Ali’s legacy? Colin Kaepernick: NFL quarterback knelt for anthem, starting a storm

“Here’s a guy who was very articulate and said things that normally, people with his skin color wouldn’t say,” Holyfield recalled.

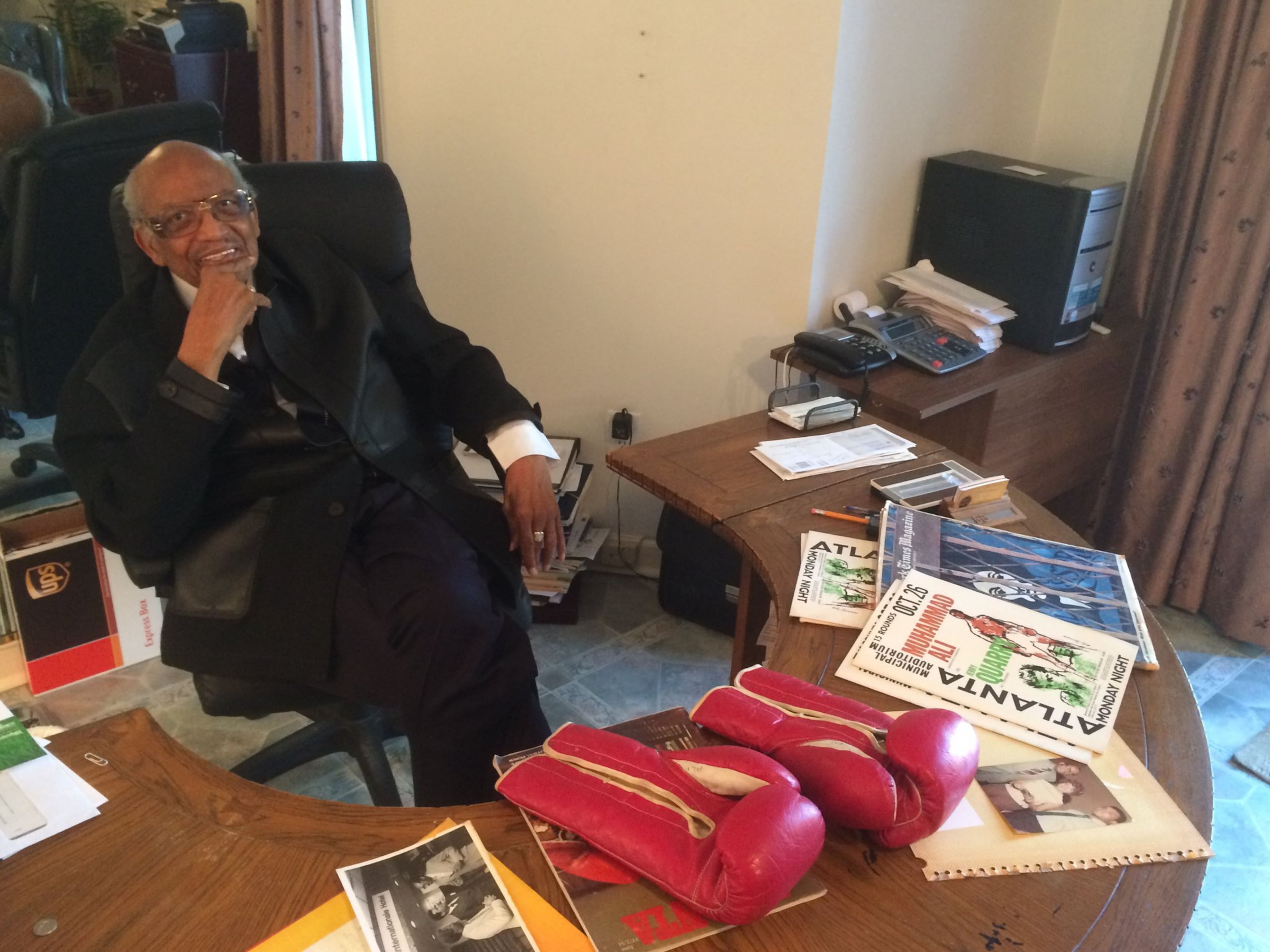

His return to the ring in Atlanta was set in motion when local businessman Harry Pett, who had family connections to a sports marketing firm, contacted state Sen. Leroy Johnson in the summer of ’70. If you can provide the venue, Pett told him, we can get a contract with Ali.

Johnson – the first black lawmaker elected to the Georgia Senate after Reconstruction – ran with the idea.

“I had not been much of a fight fan before that,” the late Johnson told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution several years ago. “The thing that energized me was that the New York boxing commission said he’d never fight again in this country. To me that became a challenge, a challenge against the system.

“Obviously we made some money out of it and I’m glad we did. But I was more concerned about doing what the system said we couldn’t do.”

Fans flocked to the Atlanta Municipal Auditorium to see the bout, which late boxing writer Bert Sugar dubbed “the greatest collection of black power and black money ever assembled up to that time.”

Stronger and much quicker than his opponent, Ali dominated the fight, unleashing a fury of blows against Quarry in the opening round.

“(Ali) has certainly appeared, in the first round, to have lost none of his swiftness,” one seemingly surprised commentator said. “He is still plenty fast and his left jab is still a dynamite punch.”

»RELATED: The power of Malcolm X

The fight was called after the third round as Quarry bled profusely from a large gash over his left eye. Ali’s comeback was complete.

He went on to continue his storied career, and the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction the following summer. But it was his actions outside the ring that inspired generations of Americans and gave modern-day athletes the platform to speak out against social injustice, Holyfield said.

“He brought countries and people together,” he said, adding that Ali set the stage by giving a voice to “anybody who wants to make this world a better place.”

BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Throughout February, we’ll spotlight a different African American pioneer in the Living section every day except Fridays. The stories will run in the Metro section on that day.

Go to www.ajc.com/black-history-month/ for more subscriber exclusives on people, places and organizations that have changed the world and to see videos and listen to Spotify playlists on featured African American pioneers.