Fate of the Iron Horse, a contentious UGA icon, is again up in the air

Many colleges and universities have at least one site of ritual, a symbolic place students must visit or an emblematic act they must do while enrolled.

At Ole Miss, it's tailgating in The Grove. At Auburn University, toilet papering the live oaks at Toomer's Corner after a win — that is before an Alabama fan poisoned the iconic trees and did jail time for committing death by herbicide. (The trees have been replaced).

At the University of Georgia, there are several customs: ringing the bell at the Chapel Bell Tower after a Dawgs’ win or upon graduation; not walking under the iron Arch along Broad Street until immediately after graduation, lest you not graduate on time or at all. Until you’ve got that degree, you walk around it.

Another is driving 18 miles south of campus to Watkinsville to watch the sun rise or set through the mane and withers of a 2-ton, 12-foot-tall iron horse sculpture in the middle of a field.

That sculpture, commonly known as, well, the Iron Horse, has stood in the field for 60 years, a symbol of why modern art can be difficult to understand, hard to accept and sometimes the target of violence. What began as an attempt in 1954 to bring avant-garde, public art to the oldest public university in the nation instead ended in one of the most infamous riots on a college campus. Initially, the sculpture was placed at Reed Hall. But student reaction was so swift and violent — they tried to melt the horse by piling old tires beneath it and setting them aflame — that the fire department had to turn hoses on the crowd of nearly 700 to disperse them. The horse was then banished from the Athens yard and eventually carted off under the cover of night to the Watkinsville field along Ga. 15.

As one employee who witnessed the spectacle said years later in a documentary about the episode, modern art, particularly in that setting, was too new and hard for the majority of the student body to understand, let alone accept.

“It had to do with ignorance,” he said. “There’s no other term for it.”

Now, the family, who saved the horse from becoming a heap of scrap metal and who now own it, wants to give it back to the university, saying the time has come for it to return to the UGA fold. The university agrees, but it wants the piece back on the main campus in Athens. The family wants the horse to stay right where it is.

“There’s not a decent spot on campus for it,” said Alice Noland, whose family saved the horse and now owns it. “The fact that the farm is named for the horse, why would you move it?”

But Noland’s reasons are also sentimental, she said, because she grew up playing around the horse on family outings, tying kites to its hooves if there was enough wind.

University spokesman Greg Trevor said it’s on-campus living — or nothing.

“If the University is going to own the Iron Horse, then we want it to be back on campus,” Trevor said in a statement.

The recent standoff is the latest turn in the saga of the Iron Horse, also known as “Pegasus Without Wings.” The massive piece was created by the late renowned sculptor, Abbott Pattison. It and the controversy of its origin have been the subject of a PBS segment, a documentary, and made it a tourist attraction with its own TripAdvisor page. Yet, as the family and university quarrel over the fate of the earthbound Pegasus, rust is eating away its hooves. It’s a constant target of graffiti and more aggressive forms of vandalism. All of this for a monumental piece of art by a sculptor whose work is part of the permanent collections of two dozen museums including the Whitney in New York City and the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Given the history of it, the importance of it in the artist’s career, this work quite feasibly could be worth $250,000,” said Jeffry Loy, an Atlanta sculptor who has done conservation work for the City of Atlanta, MARTA and who served as a project manager for Fulton County Arts & Culture. “It definitely needs to be conserved.”

From peace to protests

When they are in bloom, a field of sunflowers provide a brilliant backdrop for the horse, welded from quarter-inch thick, heavy-gauge steel. Even on a winter day, when the field of sunflowers is little more than a swath of dead stems and pads, at a distance the sculpture looks majestic. It’s abstract, vaguely Etruscan, the undulating steel of its mane glinting in the sun. But on closer inspection, the horse bears deliberate scars that harken back to 1954, when it was introduced to the student body.

Revered Georgia painter, Lamar Dodd, for whom the university’s college of art is named, was director of the art school in the 1950s. He invited Pattison to be a visiting sculptor in residence in 1954. Pattison, an instructor at the Art Institute of Chicago, was winning awards and gaining a national reputation as a classically trained sculptor gifted at rendering abstract forms in bronze, stone and steel.

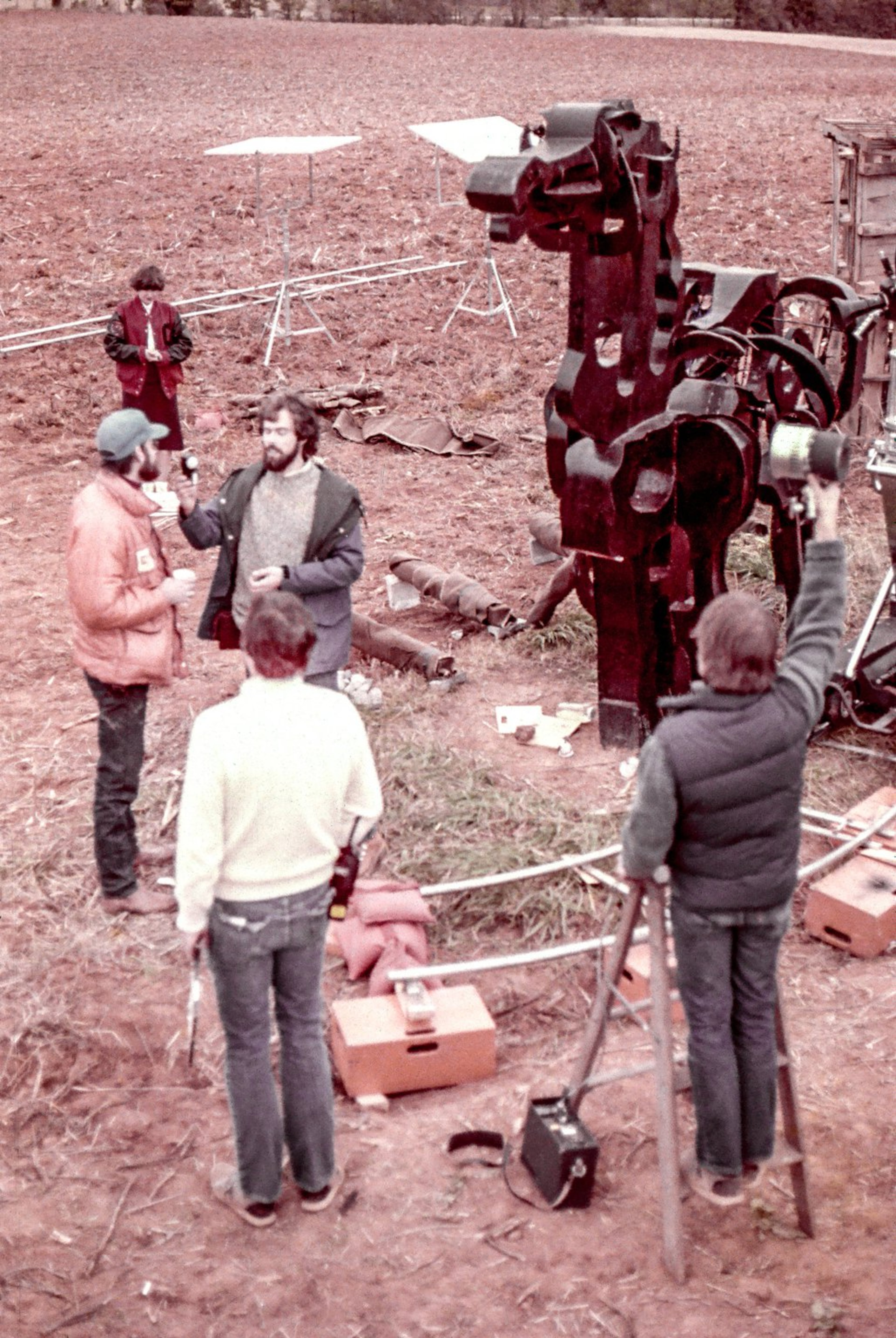

His first work at UGA was a marble sculpture called “Mother and Child,” which is still on campus, behind the fine arts building. He talked with students as he worked, answering their questions as he wielded his mallet and chisel. Its placement went largely without incident. Then Pattison turned his attention to another project. As detailed in the 1981 documentary by William VanDerKloot, “Iron Horse,” Pattison began working on something so large “it was like the building was giving birth to this piece.” He welded steel plates, something new for figurative sculpture at the time.

Months later, when it was done and wheeled out of the fine arts building, it immediately caused a stir. Within hours of it being placed near the then-brand new Reed Hall, crowds of students began attacking the sculpture. They beat it with boards, threw paint on it, lit a fire under it, gathered piles of manure and placed under it, and tied balloons under the back of its belly to mimic testicles. The mayhem lasted hours. At least one professor likened the behavior to burning books.

Dr. Don W. McMillian, who appears in the documentary, admitted to VanDerKloot that he was one of the ring leaders. He and his roommate gathered rope and manure.

“We got some hay and newspapers and some other people got some old tires from some of the filling stations around, and it got night, and we decided that that was the time to have the bonfire,” McMillian said in the film. “Every time the horse would pop, (from the heat) the crowd would yell and cheer.”

The fire department finally quelled the blaze and mob.

L.C. Curtis, then a professor of agriculture, said in the film that “full-grown men, full professors in charge of departments, took sides on this and it was a well-divided thing. Half the people wanted it; half the other people didn’t want it.”

Within 24 hours, the horse was carted to a barn off campus where it languished. Pattison said the whole episode was “devastating.” Five years later, the Curtis family asked Dodd if they could move it to their farm in Watkinsville. Dodd gave his blessing. According to Curtis family lore, Dodd said, “‘I’ve never liked the piece anyway, so go ahead,’” Patricia Curtis said recently.

“My husband heard they were going to sell the horse for scrap metal,” said Patricia Curtis, daughter-in-law of L.C. Curtis and Alice Noland’s mother.

Loy, the conservator, who helped restore the Noguchi Playscape by legendary sculptor Isamu Noguchi at Piedmont Park in the 1990s, said the response was typical.

“In the public art world, there is a torrid history of not being accepted at first, but then finding acceptance later,” Loy said.

Once the horse went to the farm, it didn't take long for students to find it again. Through the years, students have painted it pink, written their names or messages on it in marker, or even crudely etched their sorority and fraternity symbols into its haunches, flanks and chest. In 2016, four UGA students died in a car crash returning from a pilgrimage with a fifth friend to the horse to celebrate the end of the semester. Only one of the five survived the crash.

The Curtis family eventually had the sculpture bolted to a concrete pad because people would periodically knock it over.

Pattison’s son, Harry, did not respond to a request for comment about his father’s iconic work, nor about its fate.

Noland, whose father and grandfather saved the piece, said while she doesn’t like that the horse has been defaced, “it’s almost like it’s part of its evolution.”

Continued controversy

About eight years ago, the family sold about 650 acres of the farm to UGA as an agricultural research facility, except a 20-foot by 20-foot section where the horse stands. The University named the portion of the farm The Iron Horse Plant Sciences Farm. Now the Curtis family wants to deed the remaining 400 square feet to the school, on the condition the horse stays where it is.

“Watching the sun rise and set through the ribs, examining the positive and negative spaces of the horse,” said Patricia Curtis of what people who see the sculpture in the field enjoy. “Moving it would be depriving people an opportunity to enjoy art in nature.”

Noland said they’d also like to turn repair and maintenance of the piece over to the university, with its bigger budget and art school.

Looking at photographs of the damage to the piece, Loy said the rust could be addressed and perhaps the etchings and graffiti could be minimized. And yet, though he said he sees the markings as defacement because it has been continuous since the horse was unveiled, “it’s now part of the history…You then must look at the piece in a different way.”

If UGA were to get the Iron Horse on its main campus, however, Loy said he’d advise against leaving it outside and would suggest putting it in a space where it could be conserved.

Pattison, who died in 1999, said in the documentary that he didn’t “think the artist is a sacrosanct individual. He must expect to tangle, sometimes, with views of what he’s made.”

But he also said this of his contentious piece: “I decided to weld it so strong, it would endure forever.”

Exactly where it endures just may not be resolved anytime soon.