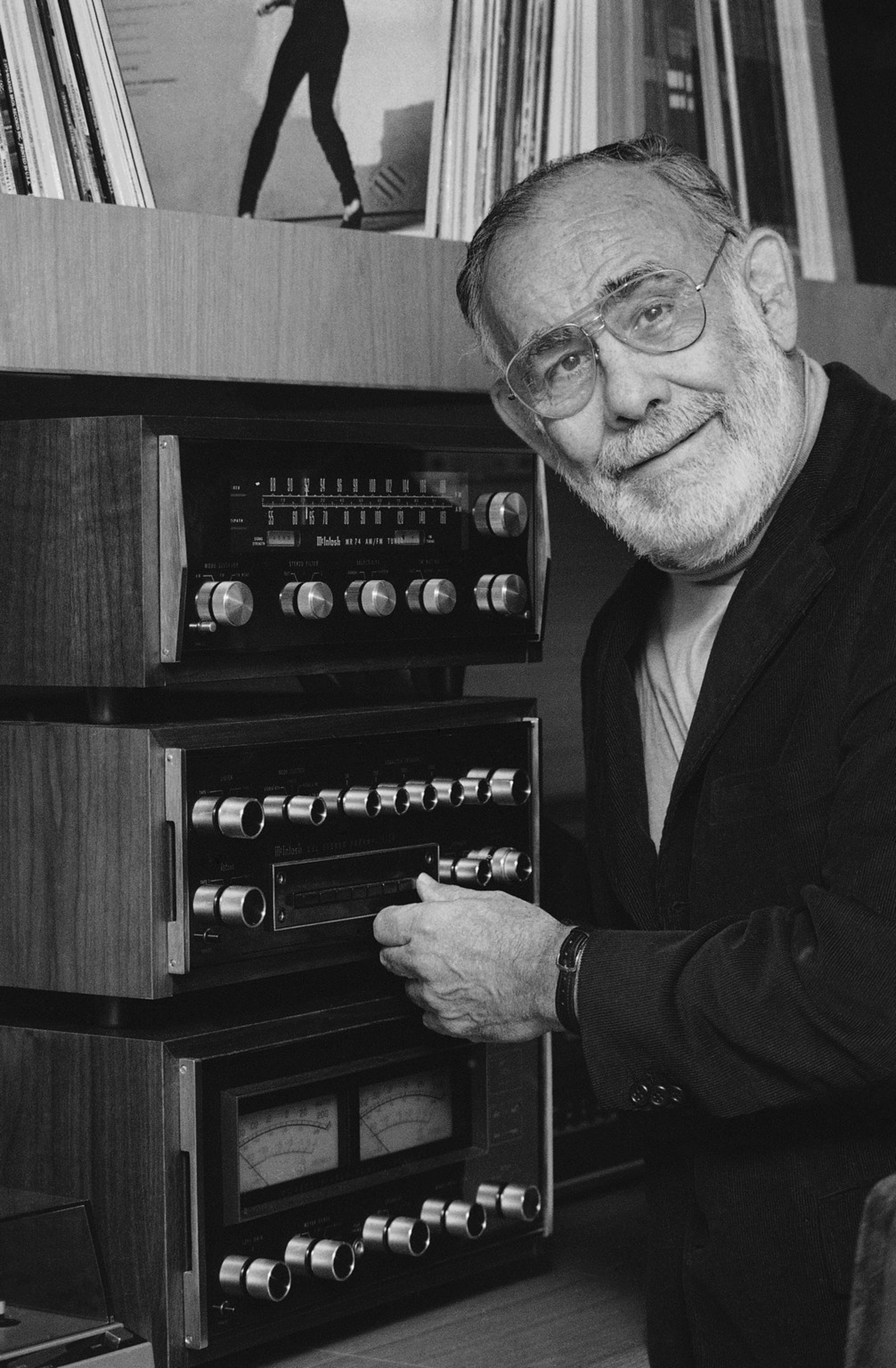

Saluting a landmark producer

Up until 1949, Billboard magazine categorized music made by black people with the offensive term: “race music.” That year Jerry Wexler, a young writer for the magazine, suggested “rhythm and blues.” The label stuck.

At a stroke, he had elevated the national conversation about music.

After he left Billboard and joined Ahmet Ertegun as a partner in Atlantic Records, Wexler produced some of the greatest albums by such artists as Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett. Wexler was not a musician but had an ear for hits and the ability to bring out the best in the label’s artists.

The Atlanta Jewish Music Festival's Spring Showcase, which begins on March 12, will celebrate the music of Jerry Wexler with a performance by the ATL Collective March 14.

What executive director Joe Alterman wants to show with the festival is that, along with producing great songwriters and musicians, the Jewish community often played a unique role in the evolution of American music by crossing boundaries and bringing different cultures together.

Like Art Rupe at Specialty Records in Los Angeles, and Phil and Leonard Chess at Chess Records in Chicago, Wexler heard music by African Americans, appreciated it, knew he could make it profitable and bring it to a white audience.

Jews and African Americans "have a very unique history in this country," said writer, spoken word artist, rapper and poet Adan Bean. "It's this incredible musical marriage that I think is beautiful."

Bean will serve as a guide during the course of the evening, giving spoken-word interludes between performances by the ATL Collective, offering the story behind hits such as “In the Midnight Hour” by Wilson Pickett and “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” by Aretha Franklin.

“This music is likely pretty familiar for a lot of people,” said Bean. “But I’ll be providing the narrative and storytelling aspect of it. People will hopefully be experiencing this music again for the first time.”

Among the other events that are part of the festival is a performance by Duchess, a jazz vocal trio singing the “Jewish American Songbook” and the Clark Atlanta Philharmonic Society performing “Annelies,” a full-length choral work based on the “The Diary of Anne Frank.”

Interlocutor Adan Bean served in the same role at last year’s salute to Leonard and Phil Chess, who brought Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Bo Diddley to national prominence.

White record producers often exploited black performers, and Bean’s version of the Chess story included that element. “Like any great flower, there’s a petal that’s beautiful, but there’s thorns at the bottom,” he said

Wexler’s business dealings were more straightforward, said Alterman. “People didn’t hate him.”

Part of the genius of producers such as Wexler was simply the ability to recognize great music, wherever it came from. (Wexler had a hand in sponsoring the creation of Capricorn Records, fostering the flowering of the Allman Brothers and Southern Rock.)

For African American musicians, figures such as Wexler and the Chess brothers gave them access to an audience that they might not get on their own. “They were able to get through the door that a black artist couldn’t get through,” said Bean.

But great producers also had insight into the artist and the song. Aretha Franklin was seeing little success at Columbia Records, where she was positioned as a jazz singer, and Wexler convinced her to sign with Atlantic in 1966. Throughout the rest of that decade and into the next she recorded 14 albums for Atlantic, where Wexler gave her more control over her songs and brought out her churchy soul.

“Let her be comfortable. Let her play piano. Let her develop the rhythms, horn riffs, and backing vocals that will open her heart and expose her soul. Let her go, and go she did,” he wrote in his autobiography.

Bean adds that empathy extends to Jewish songwriters, such as Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, George Gershwin and Carol King, whose music touched the sympathetic strings of the black experience.

When Carol King wrote “Natural Woman,” she was speaking in her own voice. “This was a true authentic emotion for her,” he said. “But when you hear that song in the voice of Aretha Franklin, that incredible instrument, then you see those two things were made to be together. That’s a testament to the beauty of music, and the interdependency and connectedness of humanity.”

EVENT PREVIEW

Atlanta Jewish Music Festival. March 12-15, 2020. atlantajmf.org

Duchess

A jazz vocal trio, performing the Jewish-American songbook,

7:30 p.m., March 12. $35-80; Richard H. Rich Auditorium, Woodruff Arts Center, 1280 Peachtree St., Atlanta.

The Wind-Down

A Young Professional’s Music Shabbat with The Well

7:30 p.m. March 13. Free. Urban Tree Cidery, 1465 Howell Mill Road, Atlanta.

The ATL Collective

The ATL Collective Relives the Sounds of Jerry Wexler and Atlantic Records

8 p.m., March 14. $35-$50. City Winery at Ponce City Market, 650 North Ave., Atlanta.

Annelies

A choral work by James Whitbourn, performed by the Clark Atlanta University Philharmonic Society.

4 p.m., March 15. Free. The Temple, 1589 Peachtree St. NE., Atlanta.