How Aretha turned ‘Respect’ into a feminist anthem

When Aretha Franklin left Columbia Records in 1966, she was struggling commercially.

The label had her singing jazz and other material, including an attempt to cash in on the “The Shoop-Shoop Song,” already a hit for Betty Everett. Columbia provided the arrangements and placed Franklin in front of polished studio musicians.

But the combination wasn’t working. After Columbia lost $90,000 on her records, and offered her a less advantageous contract, Franklin declined to renew, and signed with Jerry Wexler at Atlantic Records.

In January, 1967, recording at the Fame studio in Muscle Shoals, Ala., Wexler let Franklin write her own material, think up her own arrangements and use her sisters for backup singers.

But he did something else that created an organic feel missing from the Columbia sides.

“The thing that was so ground-breaking, and different from all of the songs she’d recorded beforehand, is (Wexler) did have her play the piano while she sang,” said David Hood, a bassist and a member of the “Swampers,” the famed Muscle Shoals session players who would open up their own studio a few years later.

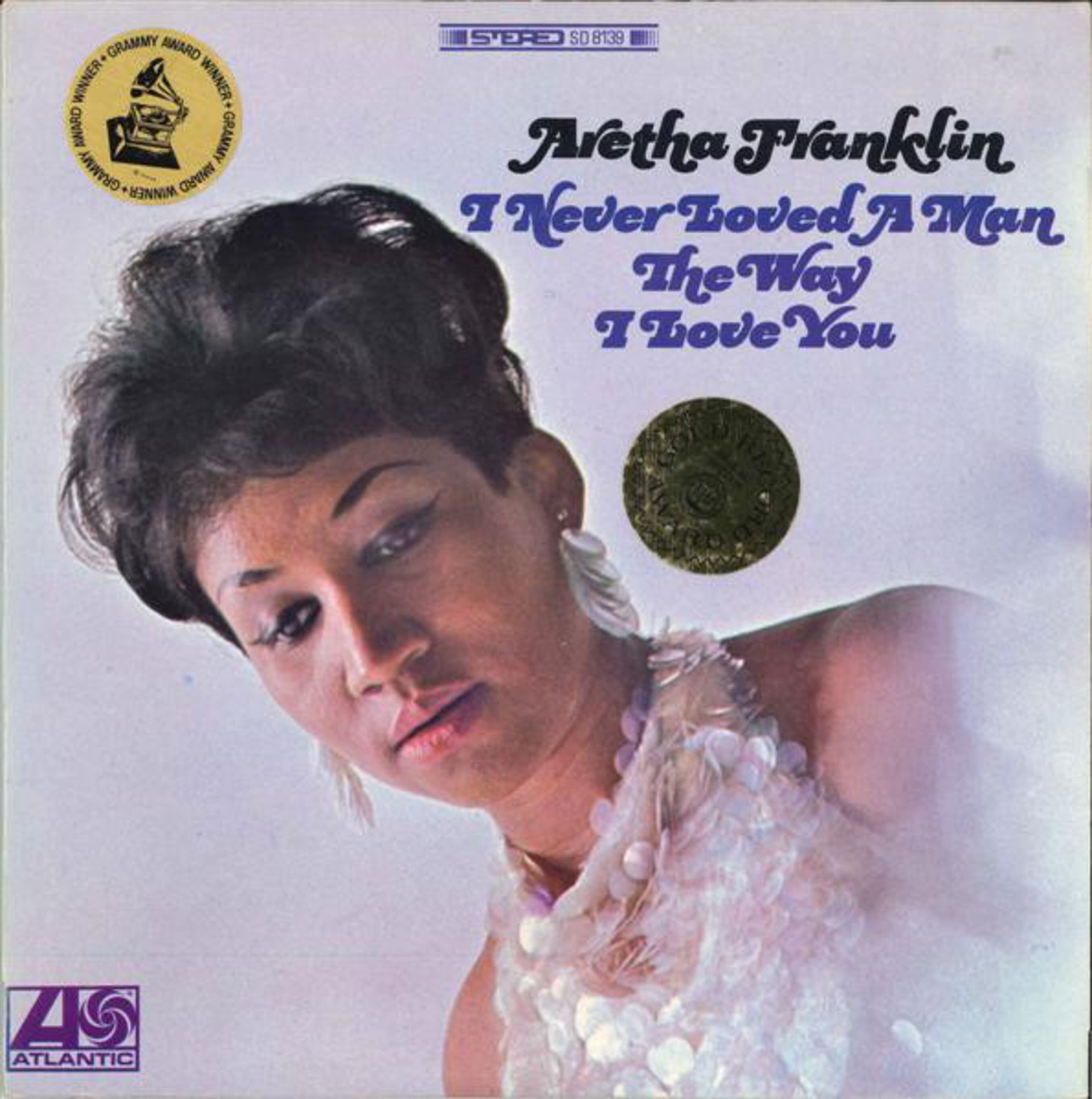

Hood set aside the bass and played trombone in the horn section on that first date, a session that created “I Never Loved A Man (the Way That I Love You.)”

Recording voice and piano at the same time created some acoustic challenges, he said. “That involved having to cover the piano, where they could have some separation between the vocals and the piano,” Hood said.

The combination of these white country musicians in the rhythm section, Franklin’s propulsive piano and her wild, swooping voice was magic.

Tempers flared after the session, however, and an argument between Wexler and studio owner Rick Hall led Wexler to record his next dates in New York City, flying in some of the Muscle Shoals musicians for the dates.

One of those New York sessions, on Feb. 14, 1967, produced the song “Respect.”

It was Otis Redding’s song. He’d released it in 1965, and it had risen to 35 on the pop music charts. But that beautiful combination of Franklin and the Muscle Shoals sound transformed the song.

In a conversation with WGBH radio in Boston, studio engineer Tom Dowd, who ran the session, described Redding’s version as a “male macho work.”

It was about conventional gender roles -- the husband demanding respect from the wife when he comes home from work.

Franklin switched the genders in the song and flipped the script.

“Otis was powerful as a man,” said Dowd. “Aretha was powerful as a woman. But times were changing. And here is an embryo women's lib, black women's lib song, where here comes this chick on strong, instead of being the shrinking violet.”

National Public Radio writes that “Franklin's ‘Respect’ became a transformative moment — not only in her career but also in the women's rights movement and the civil rights movement.”

As one might imagine, Redding was crestfallen when his song was totally kidnapped by this young gospel singer.

Wexler told Rolling Stone magazine: “Otis came up to my office right before (Franklin’s) ‘Respect’ was released, and I played him the tape. He said, ‘She done took my song.’ He said it benignly and ruefully. He knew the identity of the song was slipping away from him to her.”