One regular day decades ago, Reginald Rushin landed a notable client for the Aflac insurance company.

The young sales coordinator found himself at the offices of Jackmont Hospitality — a powerful business founded by Former Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson. Rushin greeted Jackson as the mayor proclaimed in a booming voice: “You’re the Aflac guy!”

Rushin would eventually become more than just the former mayor’s Aflac guy.

The southwest Atlanta resident became a veteran member of the Neighborhood Planning Unit system — a network of community groups built by Jackson to bring voice to individual neighborhoods at City Hall, as well as increase the political and economic power of Black Atlantans.

Under Jackson’s tenure, the NPU system was born that still operates today: 25 distinct groups that represent Atlanta’s diverse communities. The groups meet regularly to hash out issues, roundtable with city officials and vote on development changes to the area.

“It’s kind of funny how everything revolved around the fact that I had an opportunity to meet (Jackson) and he’s the one who created the NPU system,” Rushin said. “And as a consequence, years later, I ended up being a chair.”

When Jackson was inaugurated as the first Black mayor of a major Southern city in 1974, he created neighborhood planning units that were made up of many minority residents who had just discovered their political power, and were tasked with weighing in on the city’s comprehensive development plan.

“One of the first things that (Jackson) did was create an official avenue for civic participation in city government, to serve these marginalized communities to serve folks whose voices would otherwise be left out of planning processes,” said Leah LaRue, the city’s NPU director.

“He was really eager to act on his understanding of the importance of uplifting those voices of the folks who would have otherwise been left out,” she said.

Each NPU has its own leadership that sits on the sweeping Atlanta Planning Advisory Board, a committee that works directly with the city on its ever-changing comprehensive development plan, which must be updated every five years.

“If there’s a job that’s just like City Council, but doesn’t pay — that is the job of the NPU chair,” said Council member Byron Amos. “As we get calls, they get calls. As we get emails, they get emails. “As we are expected to move mountains on behalf of the citizens of Atlanta, the chairs of our NPUs are expected to do the same thing.”

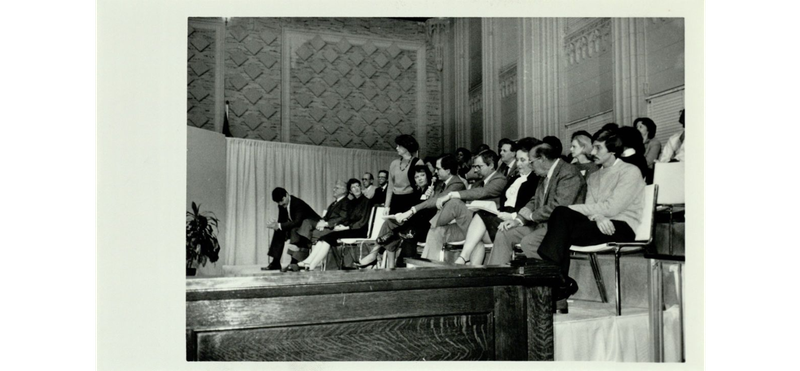

Credit: Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

Credit: Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

A bridge to City Hall

One evening in November, Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens found himself in front of a tough crowd. The mayor was on a virtual call with NPU-W, the neighborhood planning unit made up of residents from East Atlanta.

Dickens was answering questions about the city’s controversial public safety training center. The 85-acre facility will sit in unincorporated DeKalb County, just a few miles away from East Atlanta Village — the heart of the eclectic and progressive neighborhood.

The group was heavily opposed to the project and wasn’t afraid to let Dickens know. The mayor spent the better part of an hour being peppered with questions that ranged from the city’s plans to replace trees uprooted during construction to confusion over how much it would cost taxpayers.

The first-term mayor can thank Jackson for the contentious meeting. NPUs are usually well-organized with a leadership structure that can apply pressure to city officials.

“Imagine, as an elected official, what that means,” said Former City Council member Joyce Sheppard. “They’re holding you accountable, as an elected official, for what you do.”

NPU leaders agree that more outreach is crucial to keep the system successful.

Dr. Jasmine Hope, chair of NPU-K, which represents neighborhoods on the west side of downtown, said she feels the system is underutilized by Atlantans, many of whom don’t know about how the organizations interact with city officials.

“There needs to be more door knocking and going to where people are in order to really get them engaged,” she said. “Because a lot of people don’t know that they have a direct voice in what happens in their neighborhoods.”

But sometimes, NPU chairs struggle with high expectations from their neighbors to get problems solved.

Kevin Friend is the former chair of NPU-W, the east Atlanta neighborhood group that’s widely recognized as one of the most out-spoken on its disagreements with the city. Friend struggled to manage outcry against the training center in his community and ultimately stepped down from his role.

The former leader believes the citizen volunteers who make up the NPU system should be paid or receive a stipend for their work.

“For it to be a volunteer position it was just way too much stress,” he said. “I was going to work everyday and coming home to try to fix problems for a whole portion of Atlanta.”

Rushin has been involved in NPU-P for nearly two decades — he spent five years as vice chair and is currently in his 13th year as chair — likely making him one of the longest-serving members.

That means for years on top of his day job as an insurance broker, Rushin said he also manages a high number of calls from his neighbors for help for a variety of issues, from getting their trash picked up to zoning permits.

“You’ve got to really have a passion about your community and the city,” he said.

Credit: Riley Bunch/riley.bunch@ajc.com

Credit: Riley Bunch/riley.bunch@ajc.com

Keeping up with Atlanta’s changing neighborhoods

In the mid-1900s, Rev. Maynard Jackson Holbrook — father to the city’s first Black mayor — held the pulpit at the historic Friendship Baptist Church that, today, sits in the shadow of Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

Unbeknown to some, the church has on display personal items from Mayor Maynard Jackson’s life. One of his six-button suits hangs on a mannequin — showing the full extent of his stature — and a worn Bible given to him at 9 years old by his mother, Irene Dobbs, is frozen in time in a small glass case.

The 162-year-old church set the stage for an important conversation with NPU leaders and former elected officials last week about how the city and its residents can help the neighborhood advocacy system thrive.

“If Atlanta is a democracy, it’s because of the NPU more than anything else,” said Former State Sen. Vincent Fort, who was involved in the NPU system in its early days.

“The NPU system, however flawed, however contentious at times, democratizes this city,” he said.

Both NPU leaders and city officials recognize the delicate balance the system must strike: engaging as many community members as possible without letting quiet voices be overshadowed.

Sheppard, who was involved in the NPU system before she was elected to represent District 12, said she believes the biggest challenge is inclusion.

“How do we get true community engagement in terms of the diversity of all different cultures and income levels?” she said. “How do we bring people to the table — who are not just from a certain group or perspective — but sometimes the people who need it the most.”

Many leaders in the NPU system have been there for years, or decades. As Atlanta’s neighborhoods go through their own generational change, veteran community voices are looking for recruits to fill their shoes.

NPU-P works with the school system to give middle school and high school students the opportunity to earn community service hours.

“I need someone that’s younger than I, to fall in behind me and pick up where I’m leaving off,” Rushin said. “We need to engage kids in school and show them you need to care about your community and your neighborhood. By doing so, that’s how we keep Atlanta moving.”

The city is also trying to come up with creative ways to catch the eye of younger residents who want to make change in their areas.

“We want to make sure that we’re staying on top of the times and that we’re creating and promoting a system that is equitable and fair,” LaRue said. “One that really considers the entire community.”

LaRue said that means expanding outreach to renters as well as traditional homeowners in an effort to connect with Gen X and Gen Z Atlantans, in addition to baby boomers and millennials.

But diversifying the city’s neighborhood planning units doesn’t come without the possibility of tension.

“Sometimes the legacy residents are a little hesitant — which makes sense, change can be a little scary to anyone — but they’re afraid that they’re gonna have less of a voice, because you have all these newer residents coming in,” said Hope, with NPU-K.

“Everybody, at the end of the day, just wants to be heard,” she said.

You can find out more about the 50th anniversary of Atlanta’s neighborhood planning units or how to get involved in your community by visiting https://www.npuatlanta.org/50th-anniversary.

About the Author