Unique Emory exhibit explores racism through Flannery O’Connor story

“At the Crossroads with Benny Andrews, Flannery O’Connor and Alice Walker,” at the Schatten Gallery on Level 3 of Emory University’s Woodruff Library (through May 18) is a monumental enterprise and an extraordinary exhibit.

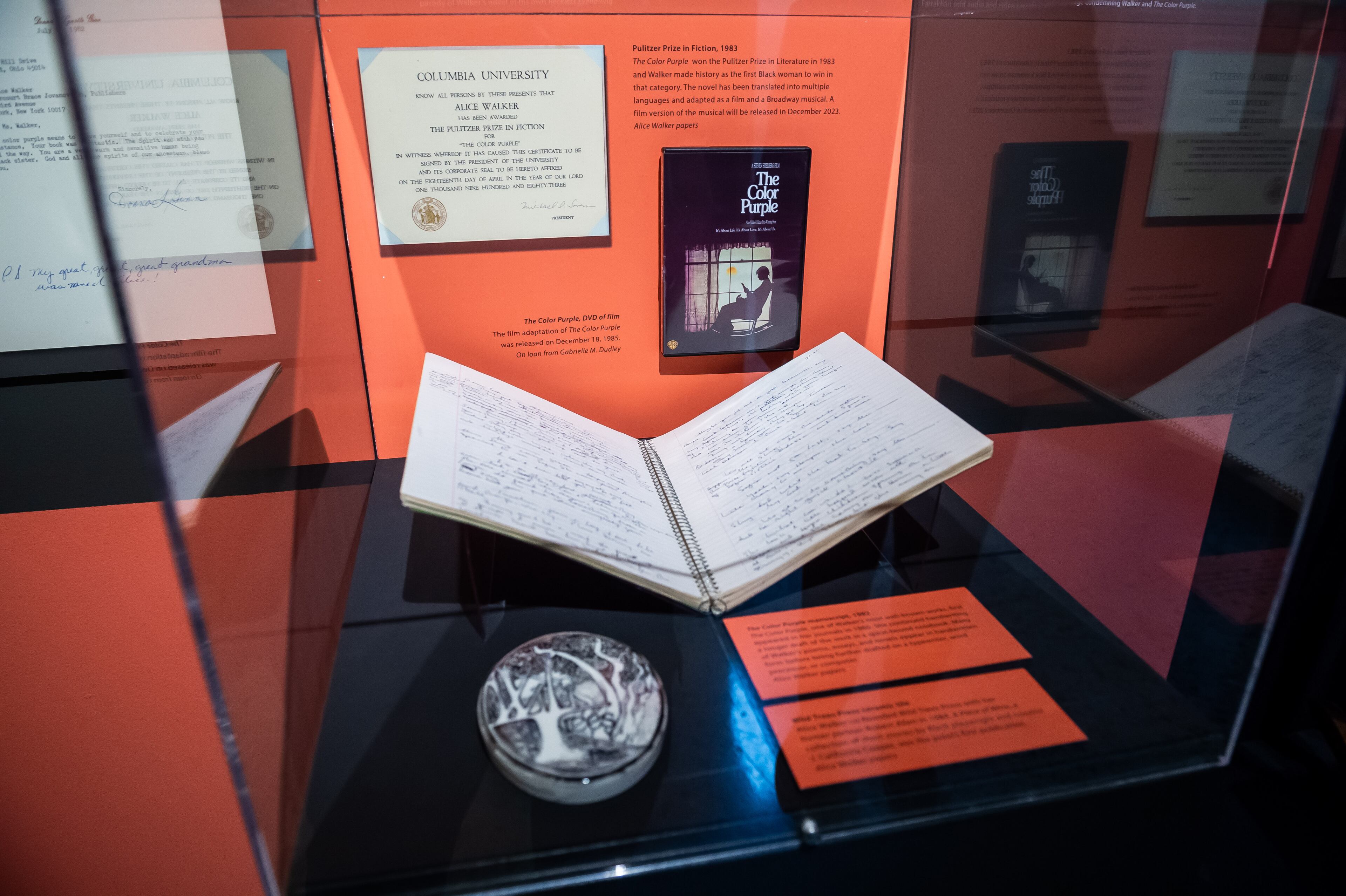

It involved five curators (Gabrielle M. Dudley, Tina Dunkley, Amy Alznauer, Nagueyalti Warren and Rosemary M. Magee) and three archival collections from Emory’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.

It explores for the first time the cultural connections and tensions underlying the careers of two writers and one visual artist who grew up as near-contemporaries within a 50-mile radius of one another in middle Georgia (in Madison, Milledgeville and Eatonton.)

Despite their equal degree of fame in literary and artistic circles, they were ultimately connected only through their relationship to a short story about cultural convergence.

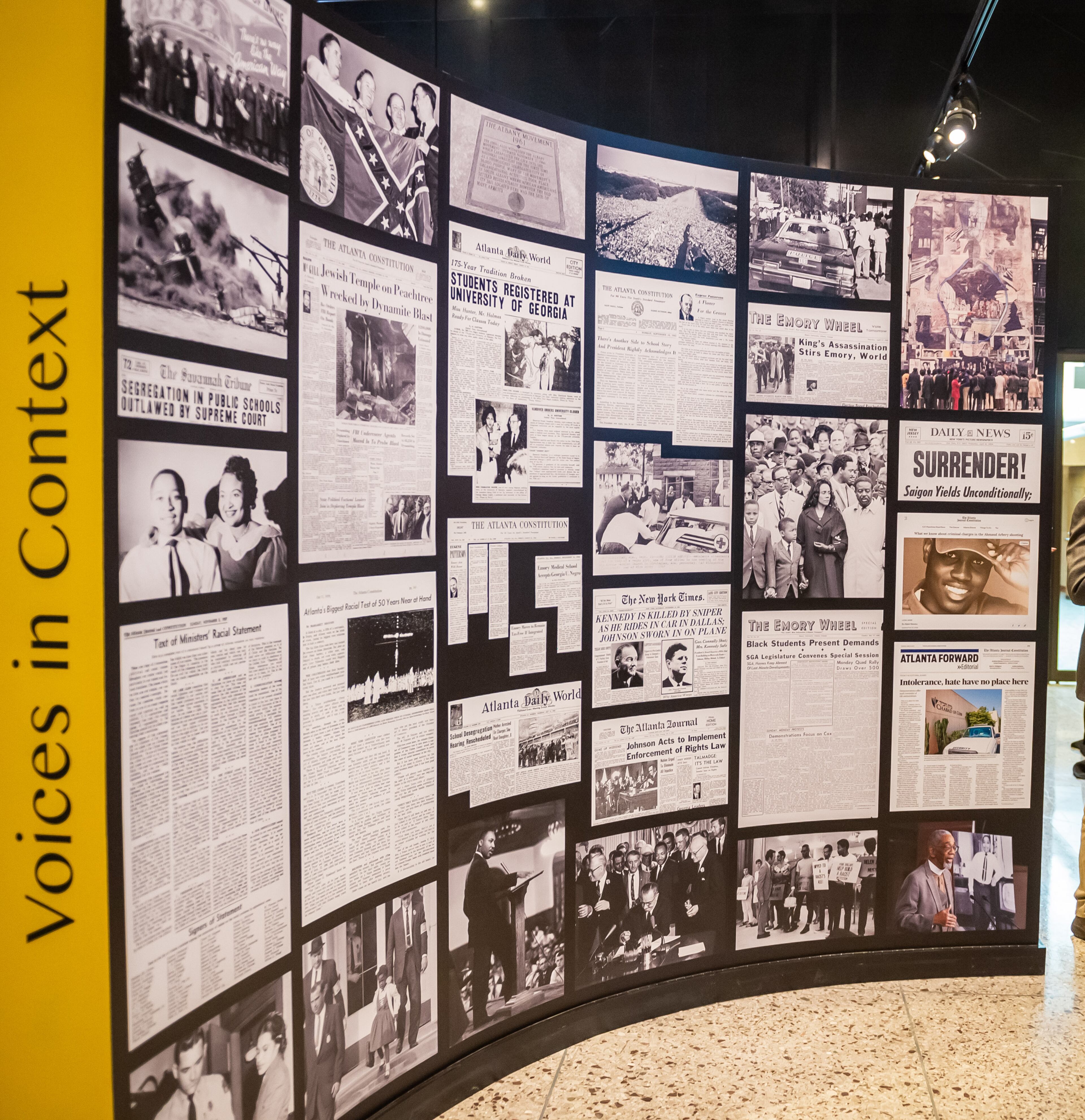

This requires a bit of explanation. The exhibition, which features a vast array of objects and manuscripts related to the careers of visual artist Andrews and writers Walker and O’Connor, is in many ways intended to be an introduction to a not quite bygone era that may be unfamiliar to some.

O’Connor’s 1961 short story “Everything That Rises Must Converge” is about what happens when a white woman, on a newly integrated city bus, sees an African American woman wearing a hat identical to hers. O’Connor’s primary focus is on the mind-set of the white woman’s college-educated son, who is embarrassed and angered by his mother’s condescending racism and who regards the African American woman’s indignant response as his mother’s justified punishment for a behavior condemned by history.

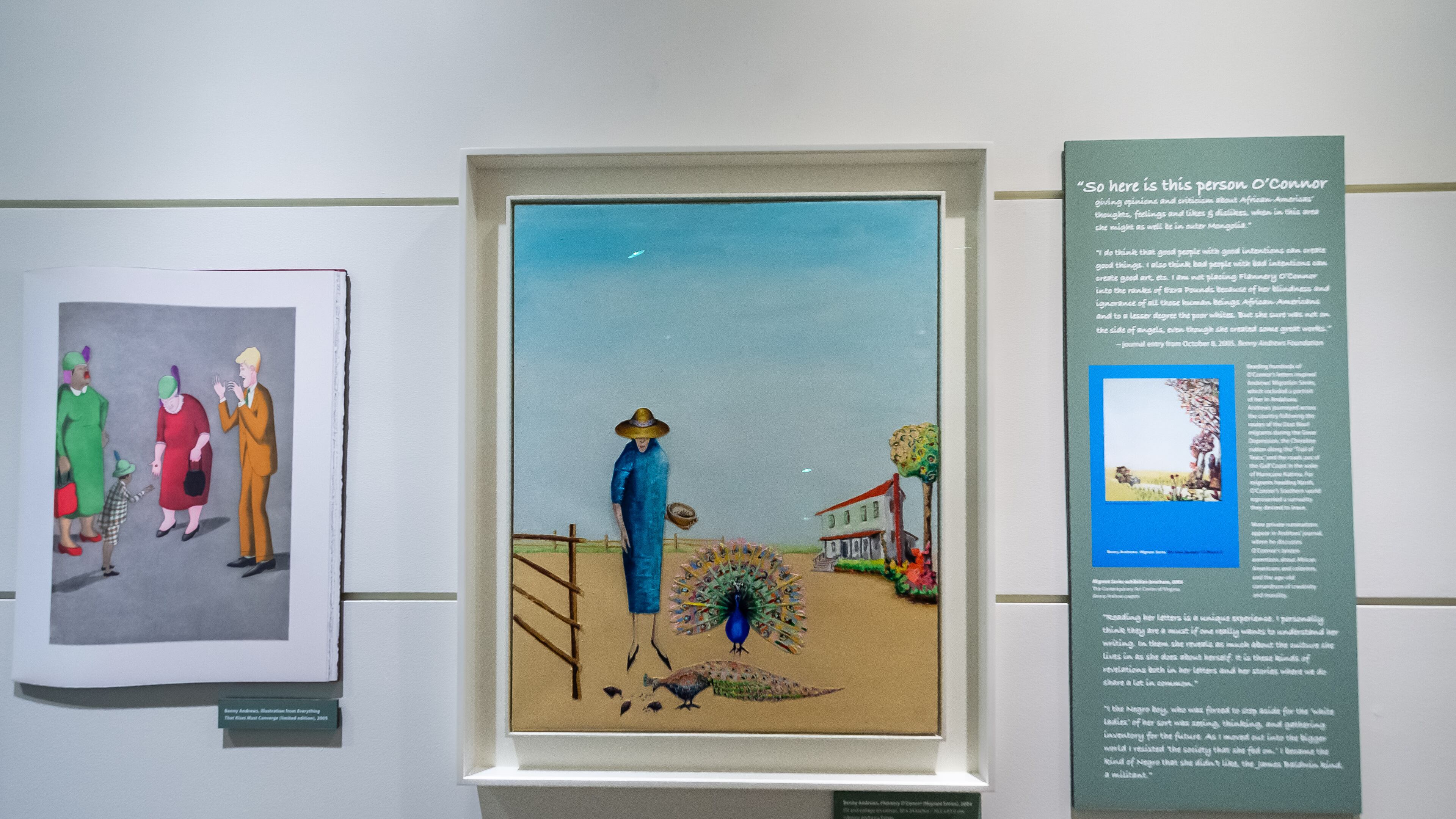

At different times, Walker and Andrews, both African American, provided independent perspectives on O’Connor’s story — Walker in the short story “Convergence” and the essay “Beyond the Peacock: The Reconstruction of Flannery O’Connor,” and Andrews through a suite of etchings for a limited-edition volume reprinting the story. These artworks form the core of the introductory display in the rotunda gallery.

Both found that the story, usually interpreted by critics as O’Connor’s deep critique of white Southern racism, remained deeply troublesome, regardless of O’Connor’s intentions.

This exhibition reveals the fraught depths of being born with a creative inclination between 1925 and 1944 in middle Georgia, in almost neighboring communities but under very different circumstances. It is a complex story, and the extensive introductory texts in the rotunda gallery include a placard explaining that the word “Negro,” once a polite descriptive term, is now regarded as unacceptable.

A similar placard in the O’Connor section of the main gallery notes that “the n-word,” used in conversation by her characters, was one for which O’Connor herself substituted a less offensive term when she gave public readings. She did this in spite of her earlier protestations when others made the substitution.

Andrews’ 2005 “Afterword” to the limited-edition book explains that he and O’Connor were kept apart not only by laws but by attitudes, in a segregated society “sustained by oppression, cruelty and murder,” and that O’Connor would not have given him entry into her life, no matter how much she delved into “things bigger than the physical world she lived in.”

In her essay, Walker writes of how, when she told her mother the essential plot of O’Connor’s short story, her mother sympathized with the physically injured White woman in an act of “total identification that was so Southern and so Black.”

This summary barely begins to describe the dimensions of this extraordinary exhibition. It makes maximum use of the ironies of the optimistic Teilhard de Chardin quotation from which O’Connor took her short story’s title: “Remain true to yourself, but move ever upward toward greater consciousness and greater love! At the summit you will find yourselves united with all those who, from every direction, have made the same ascent. For everything that rises must converge.”

The exhibition does an adroit job of navigating a vast range of subject matter, incorporating its story of the impetus for the exhibition into a single panel, “Between the Waterways & Highway 441: A Road Trip to the Fertile Ground of the Hometowns of Benny Andrews, Flannery O’Connor and Alice Walker.”

The rest of the exhibition tells the story of what unites and separates the imaginative and physical worlds of these three artists, without ever losing focus on the central premise of their shared — yet unshared — origins.

The two white curators who were responsible for the O’Connor segment, Alznauer and Magee, contribute a further curatorial statement: “We were particularly interested in the development of her creative imagination and in the evolution and deficits of her views on race. And now, we stand at these crossroads with three artists who together illuminate the profound and sometimes difficult questions this meeting represents.”

O’Connor’s childhood and adolescence are meticulously documented in the archives, which has enabled Alznauer and Magee to include a substantial quantity of O’Connor’s early works of visual art that reveal her to have had talent in that realm as well as in literature.

Ironically, the limits of the Emory archives mean that Andrews’ oeuvre is less well-represented in this regard than O’Connor’s, although his considerable achievements in the national and global art world are well documented and his biographical details amply set in context.

The segment devoted to Walker includes a discussion of her role in re-introducing the work of Zora Neale Hurston to the national literary scene and in locating Hurston’s grave — a story that, given Hurston’s often tragic biography, adds further nuances to the main themes of “At the Crossroads.”

Given the wealth of original documents from which the curators have extracted an easily followed storyline, most visitors will learn new things about Andrews, Walker and O’Connor. All visitors are likely to leave with a perspective on the three Georgia natives they had never previously considered.

IF YOU GO

“At the Crossroads with Benny Andrews, Flannery O’Connor and Alice Walker”

Through May 18. Free. Emory University’s Woodruff Library, 540 Asbury Circle, Atlanta. libraries.emory.edu, emorylib.info/fall2023hours.

MEET OUR PARTNER

ArtsATL (www.artsatl.org), is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. Founded in 2009, ArtsATL’s goal is to help build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.If you have any questions about this partnership or others, please contact Senior Manager of Partnerships Nicole Williams at nicole.williams@ajc.com.